Statistics

Based on scientific examination

We conducted almost 1800 analyses for this study, bearing in mind that for verification and control purposes we frequently performed several examinations on the same support. The supports selected for the period from the 12th to the 16th century break down as follows by country:

•Italy 345

•Germany 219

•Spain 168

•France 155

•Portugal 88

•Flanders 66

•Holland 19

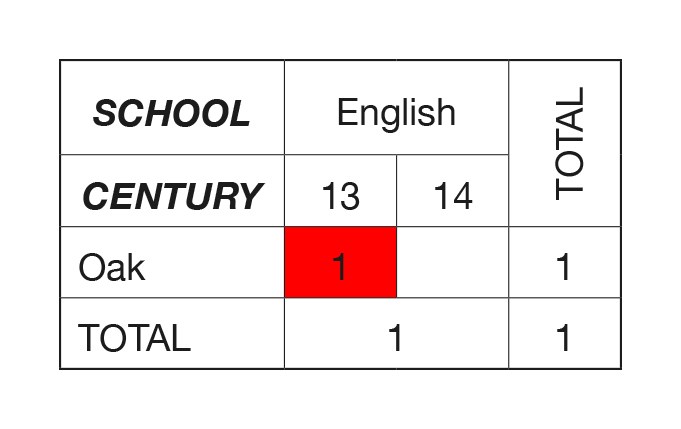

•England 1

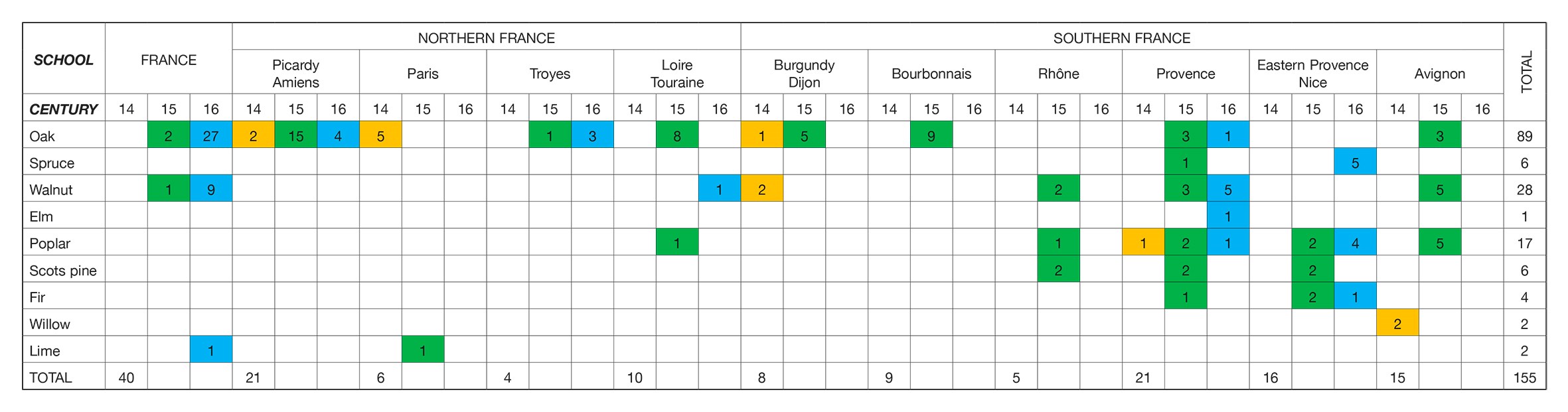

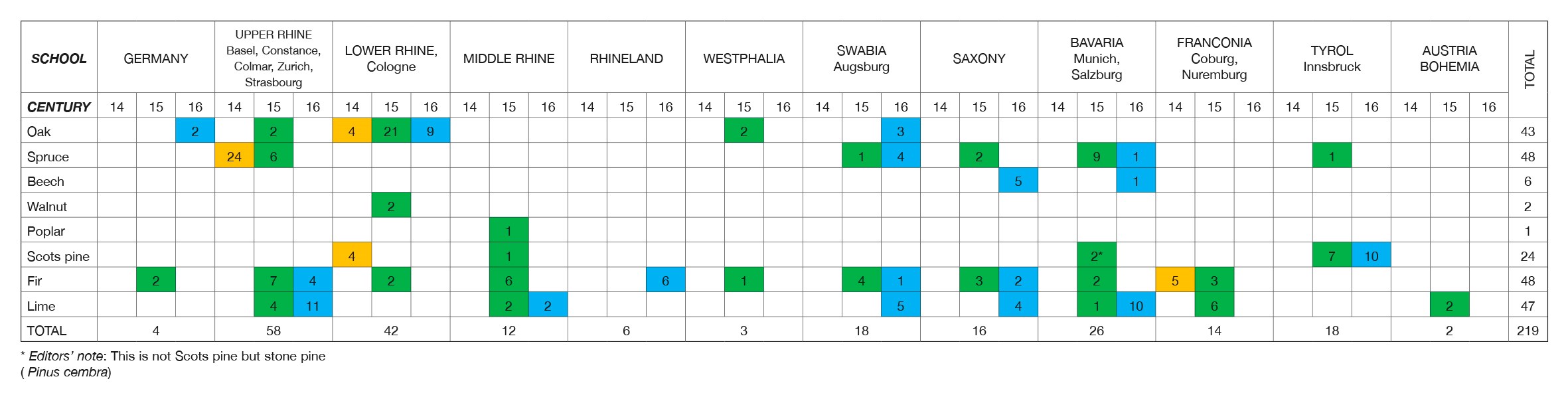

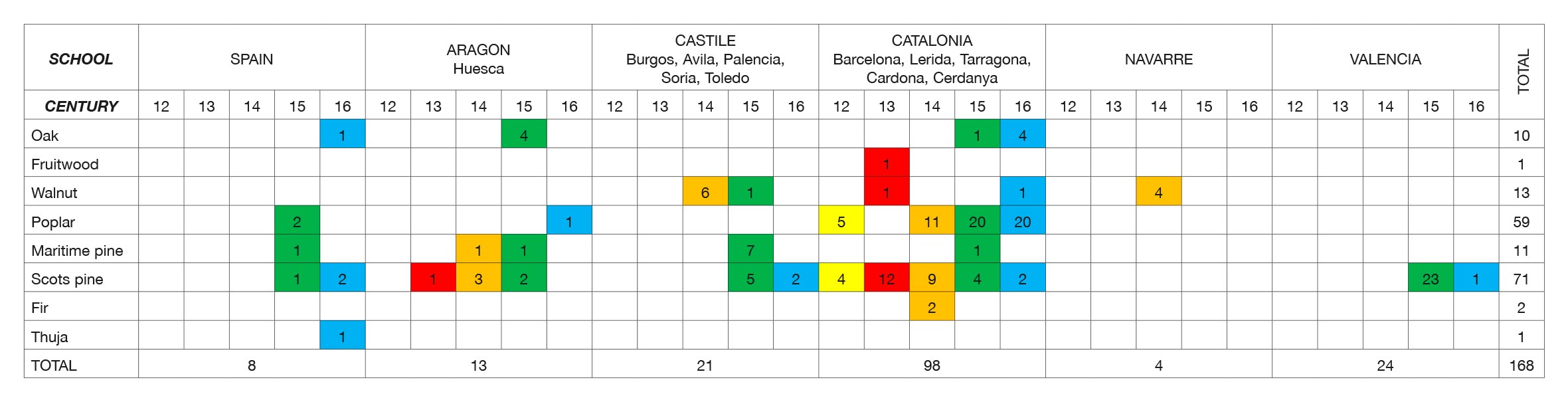

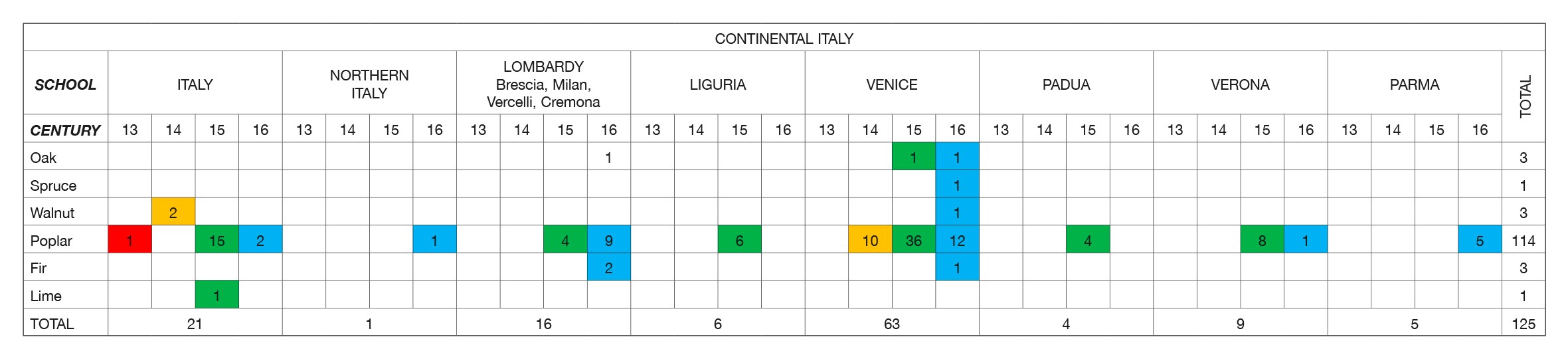

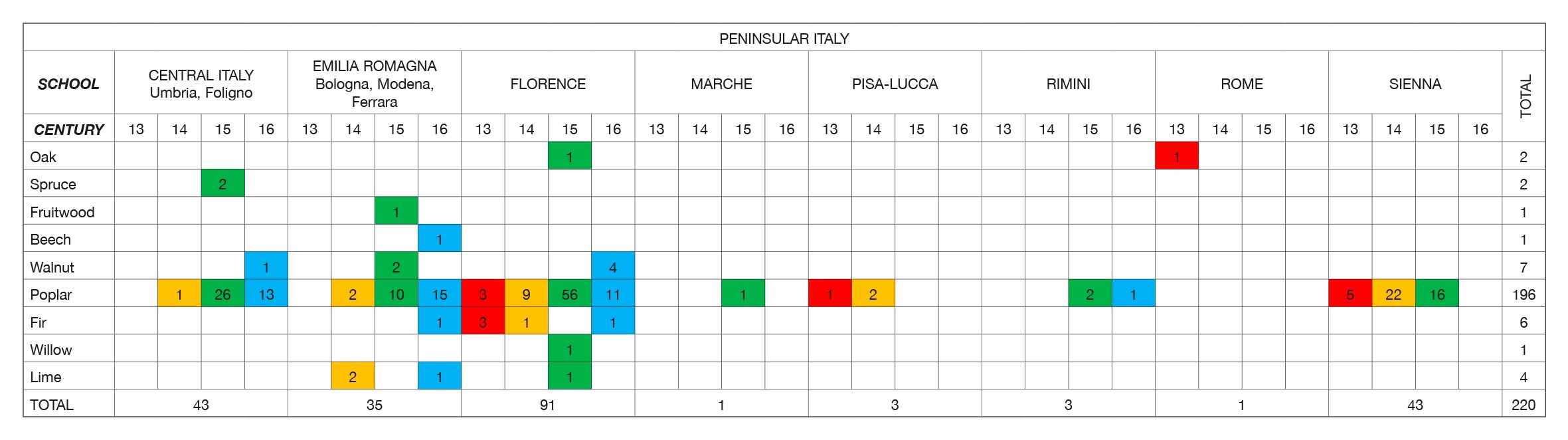

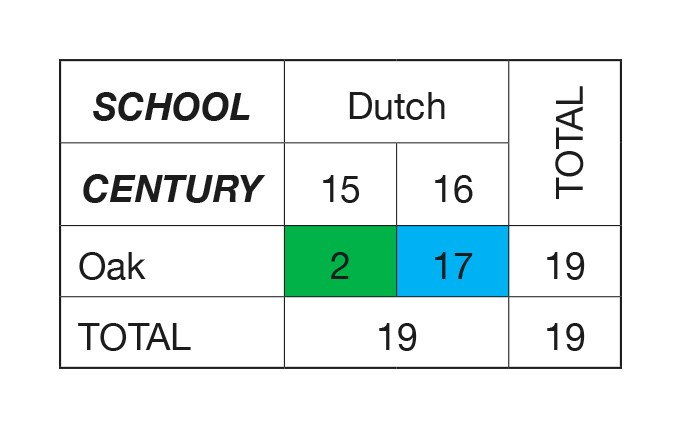

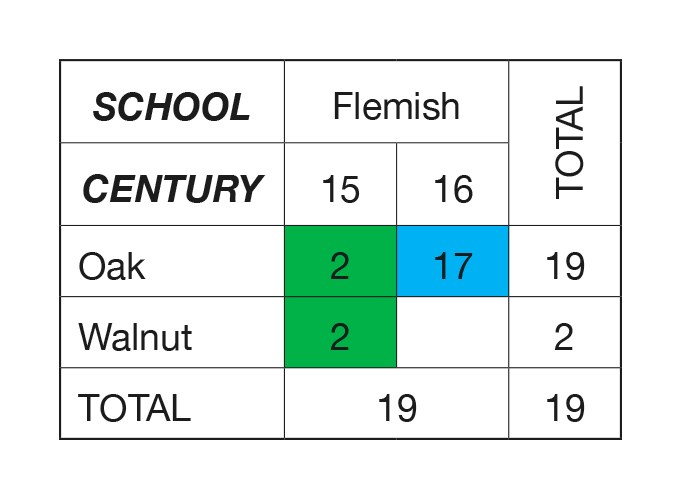

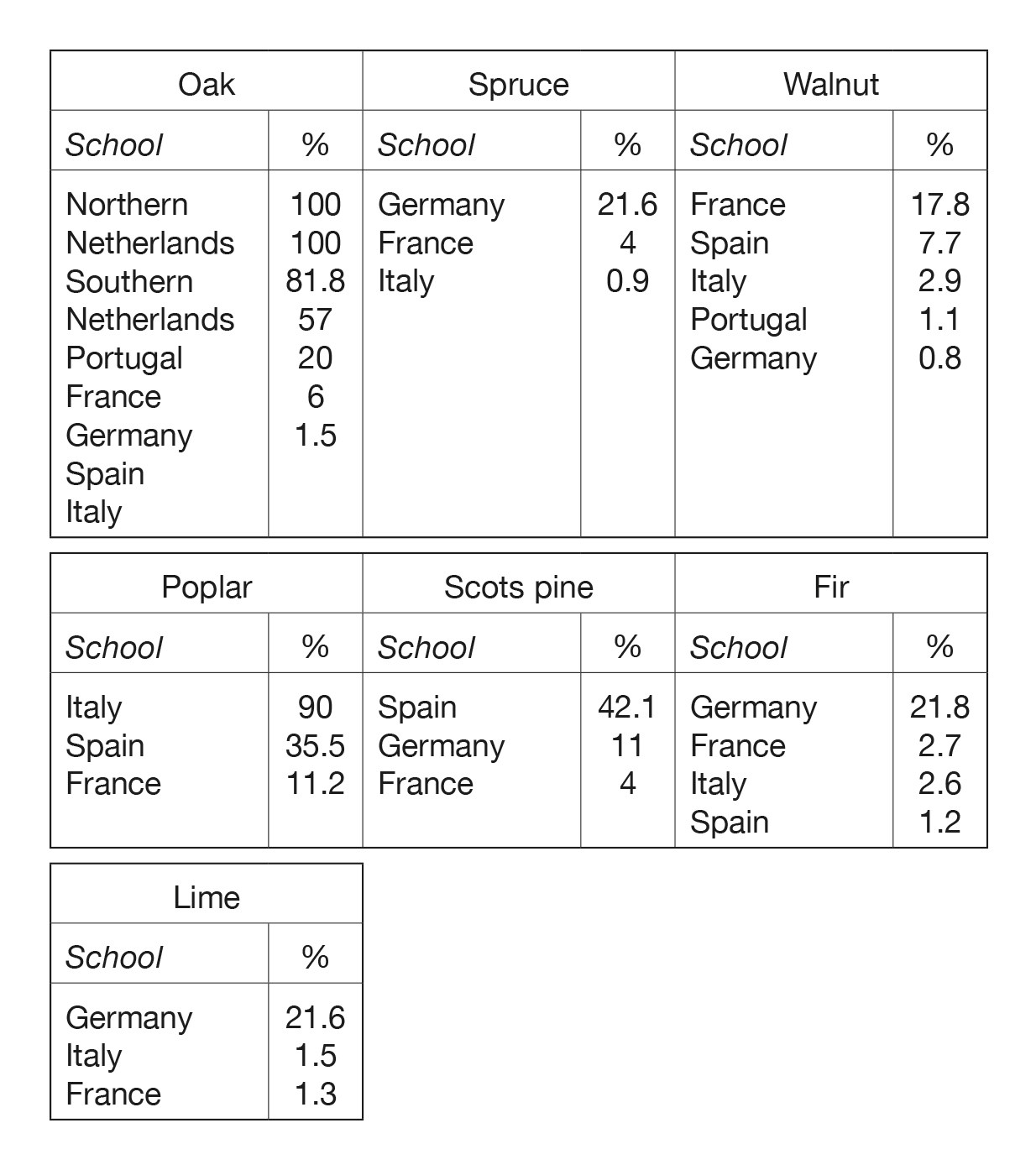

Analysis of wood samples taken from these supports identified fourteen different varieties: chestnut, oak, spruce, fruitwood (pear?), beech, walnut, elm, poplar, maritime pine, Scots pine, fir, willow, lime and thuja. The statistical tables that follow contain a breakdown of these supports by school, period, and wood species (see Tables 1–9).

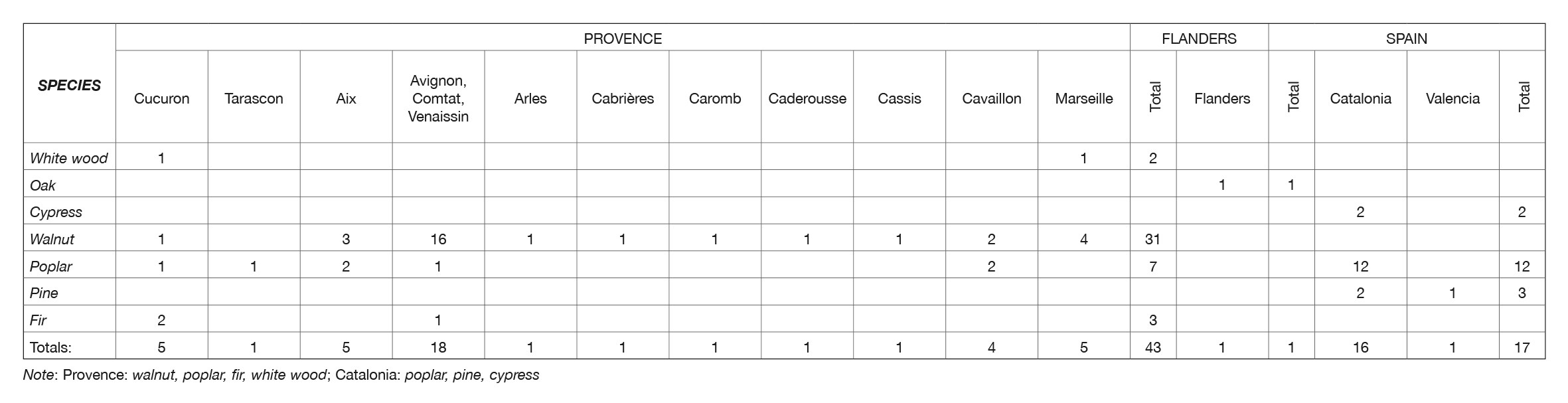

Based on contracts

Following on from the statistics described above, Table 10 contains a breakdown of the wood types used for supports as mentioned in painters’ contracts solely for Provence, Catalonia and Flanders. Despite the fragmentary character of this aspect of the study, we felt it would be particularly interesting to include the results. While recognising that they do not carry as much weight as the other sources of data, they can nevertheless be used for purposes of comparison, with the potential to refute or confirm the scientific findings.1Editors’ note: For the North European School see Wadum 1998a: 149–77.

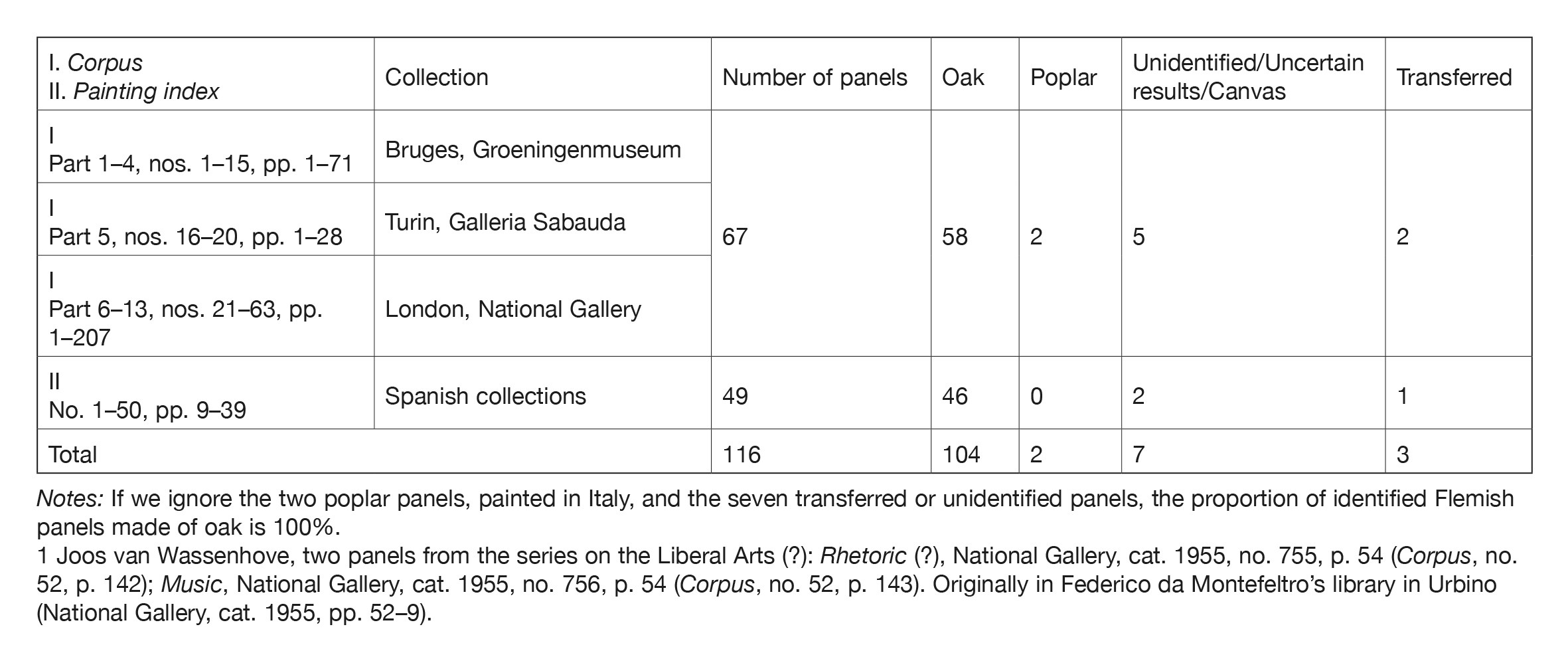

Based on the Flemish Corpus

Table 11 shows the wood species used for supports in Flemish painting according to the Corpus de la peinture des anciens Pays-Bas.2Les Primitifs flamands. I: Corpus de la peinture des anciens Pays-Bas méridionaux au XVe siècle; II: Répertoire des peintres flamands des XVe et XVIe siècles, Antwerp 1952–1954, 3 vols. Editors’ note: See other relevant publications from the Centre for the Study of the Flemish Primitives (CSFP) in Brussels (three series : ‘Repertory of Flemish paintings of the fifteenth and sixteenth century’; ‘Corpus of fifteenth century painting in the Southern Netherlands’; ‘Contributions to the study of the Flemish Primitives’), which give detailed descriptions, photographs and sometimes X-radiographic images of Flemish panel paintings in various museums worldwide (note that many of these publications have been scanned and will be available online on the website of the CSFP (http://xv.kikirpa/en/homepage.htm) in 2015. In the ‘Repertory’ series, on collections in Spain, see Lavalleye 1953, 1958; on collections in Italy, see Carandente 1968; on collections in the former Czechoslovakia, see Vacková and Comblen-Sonkes 1985; on collections in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais, see Heck 2005; on public collections in Liège, see Allart 2008. Several volumes in the ‘Contributions’ series are relevant to the study of panel supports: on the Ghent Altarpiece, see Coremans 1953; on Pre-Eyckian panel painting, see Deneffe et al. 2009; on Albrecht Bouts, see Henderiks 2011. All twenty-two ‘Corpus’ volumes are useful for their technical descriptions and illustrations – each is dedicated to a specific collection or collections. Other relevant ‘Corpus’ publications published thereafter: on the Groeningemuseum, see Janssens de Bisthoven 1983; on the Sabauda Gallery of Turin, see Aru and De Geradon 1952; on the National Gallery, London, see Davies 1971; for New England Museums (Boston, Cambridge, Hartford, New Haven, Williamstown and Worcester), see Eisler 1961; on the Musée du Louvre, Paris, see Adhémar 1962, Comblen-Sonkes 1996 and Lorentz and Comblen-Sonkes 2001; on the Royal Chapel of Grenada, see Van Schoute 1963; on the Ducal Palace of Urbino, see Lavalleye 1964; on the Hermitage Museum, see Loewinson-Lessing and Nicouline 1965; on museums in Poland, see Bialostocki 1966; on the Cathedral of Palencia, see Vandevivere 1967; on the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, see Hoff and Davies 1971; on the Hôtel-Dieu of Beaune, see Veronée-Verhaegen 1973; on the Musée des Beaux-Arts of Dijon, see Comblen-Sonkes and Veronée-Verhaegen 1987; on the Musées de l’Institut de France – Musée Jacquemart-André, Musée Marmottan and Musée Condé – see Comblen-Sonkes 1988; on the National Museum of Fine Art in Lisbon, see Lievens-De Waegh 1991; on the collegiate church of Saint Peter, Louvain, see Comblen-Sonkes 1996; on the Mayer van den Bergh Museum, Antwerp, see Mund et al. 2003; on the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lille, see Châtelet and Goetghebeur 2006; on the Los Angeles Museum of Art, see Wolfthal and Metzger 2014. The identification of the wooden supports of the paintings in that study – although obtained solely from visual observation – is interesting in the context of this remarkable publication.

The statistics set out below based, as indicated, on scientific examination, data from painters’ contracts during the period in question,3Editors’ note: Painters’ contracts from this region, primarily from the 15th century, are published in Dijkstra 1990. and on the Flemish Corpus, produce consistent results, which means that considerable weight may be placed on the rule derived from them.

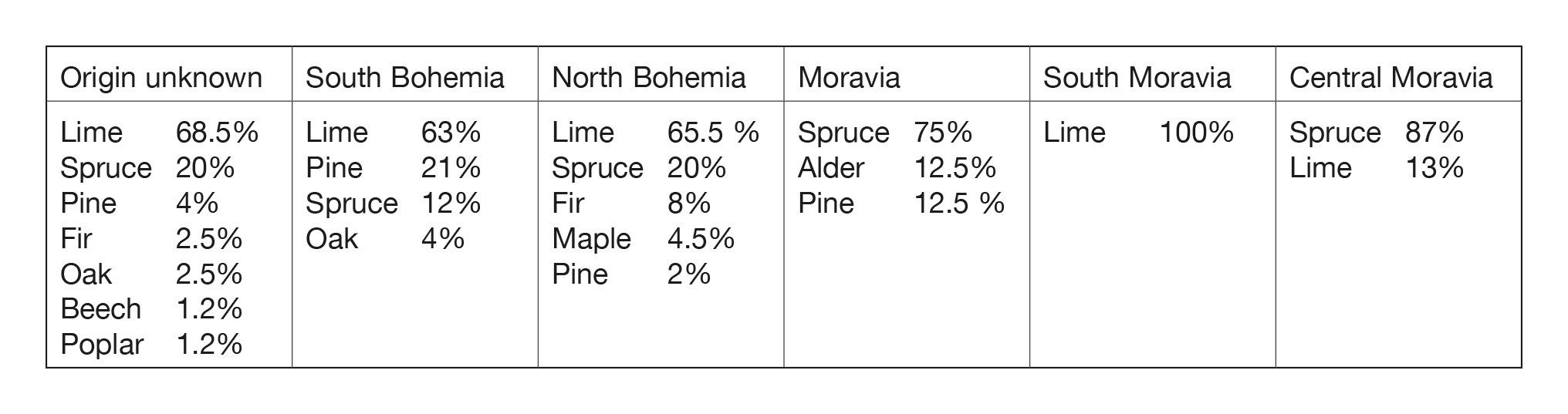

We conclude with a brief summary of statistics provided by Antonin Matejcek and Jaroslav Pesina’s publications on 14th–16th-century Czech painting. The identification of these species, although visual, gives an overview of the woods used in the regions in question, which the limited number of panels examined scientifically has been unable to provide. The results obtained are consistent, incidentally, with the outline of the Bohemian and Moravian forests, and emphasise the predominance of lime in these schools.

Table 1 French School: statistics for the type of wood used in supports north and south of the Loire based on scientific examination.

Table 2 German School: statistics for the type of wood used in supports in western, central and southern Germany based on scientific examination.

Table 3 Spanish School: statistics for the type of wood used in supports in Aragon, Castile, Navarre and Valencia based on scientific examination.

Table 4 Italian School (continental): statistics for the type of wood used in supports in northwest and northeast Italy based on scientific examination.

Table 5 Italian School (peninsular): statistics for the type of wood used in supports in central Italy based on scientific examination.

Table 6 Northern Netherlandish School: statistics for the type of wood used in supports in the northern Netherlands based on scientific examination.

Table 7 Southern Netherlandish School: statistics for the type of wood used in supports in the southern Netherlands based on scientific examination.

Table 8 English School: statistics for the type of wood used in supports in England based on scientific examination.

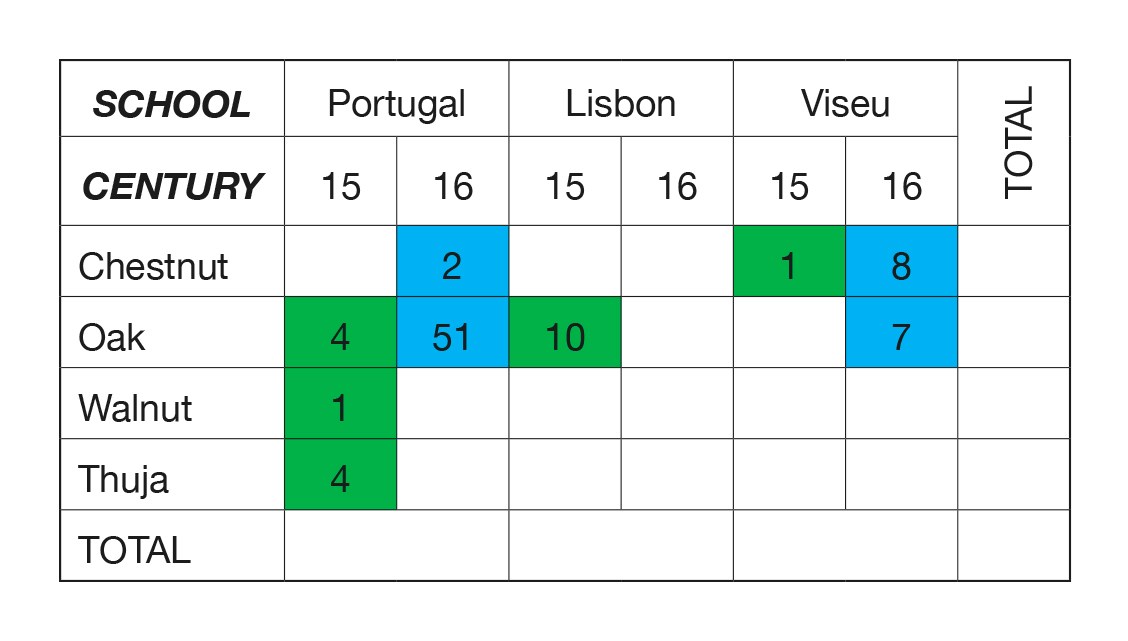

Table 9 Portuguese School: statistics for the type of wood used in supports in Portugal based on scientific examination.

Table 10 Statistics for the type of wood used in supports in Provence, Catalonia and Flanders according to painters’ contracts 1324–1569 (see also ‘Extracts from painters’ contracts).

Table 11 Statistics for the type of wood used in supports in Flanders in the 15th and 16th centuries according to the Corpus de la peinture des anciens Pays-Bas.

We learned too late of Antonin Matejcek and Jaroslav Pesina’s, La Peinture gothique tchèque, 1350–1450 (Prague 1950) and Jaroslav Pesina’s, La Peinture tchèque du XVe et du XVIe siècle (Prague 1958), to be able to include the statistics for the cited varieties or the historical map of Bohemia and Moravia that we prepared based on their data. We will merely provide a summary of these statistics below, while noting that the varieties mentioned by Matejcek and Pesina are the result of visual identification of the wood panels:

•Overall results based on 252 panels from the 14th to the 16th century: lime, 159 panels; spruce, 59; pine, 12; fir, 11; maple, 5; oak, 3; alder, 1; beech, 1; poplar, 1

Table 12 shows the distribution of these species in Bohemia and Moravia.

Table 12 Distribution of species in Bohemia and Moravia.

These statistics reveal a substantial predominance of lime and softwoods, especially spruce, for Bohemia and Moravia together. The panels listed in the ‘Moravia’ column are those that have not been localised more precisely. They are, incidentally, few in number.

Resulting rule: anomalies

The woods used by painters until the end of the 16th century correspond with a high degree of precision to the forest vegetation of the regions in which their panels were painted. This rule is so absolute that we may safely assert that the painters of this period only used locally sourced wood.4Editors’ note: Research subsequent to Marette’s study has shown this not to be the case. Indeed, dendrochronological studies have proved that most of the wood used in northern European panel painting in the 15th and 16th centuries was imported by sea from the Baltic region. See Streeton and Wadum 2012: 86‒91; Streeton 2013: 105‒22; Bonde 1992: 53–5; Klein et al. 1987b: 51– 4; Baillic 1984: 371–93. The history of trading, as we will see later, and the study, albeit fragmentary, of contracts that refer to the type of wood to be used confirm this thesis, which is further borne out by the Corpus de la peinture des anciens Pays-Bas.5Les Primitifs flamands (1952–1954), I, parts 1–4, nos. 1–15; part 5, nos. 16 and 20; parts 6–13, nos. 21–63; II, nos. 1–50.

If we accept this law, we have to view a painter’s use of a wood that was foreign to his region as an anomaly. 6Editors’ note: Research has proved that this conclusion should be strongly modified. Indeed, dendrochronological studies have confirmed that most of the wood used in northern European panel painting in the 15th and 16th centuries was imported by sea from the Baltic region. See Streeton and Wadum 2012: 86‒91; Streeton 2013: 105‒22; Bonde 1992: 53–5; Klein et al. 1987b: 51–4; Baillic 1984: 371–93. Practical examples of such anomalies include the use of walnut by the northern schools; fir by the English and Flemish schools; spruce by the Spanish and peninsular Italian schools; thuja anywhere other than the southern Iberian Peninsula; beech in central and southern Spain; and maritime pine in Aragon and Catalonia. Analysis of the statistics also reveals the dominant and characteristic species from which we can draw practical lessons.

If we apply the above rule, we have to categorise as anomalies the two walnut panels attributed to Hans Memling (ca. 1430–1494) with the Mystical Marriage of St Catherine of Alexandria and a Praying Donor with St John the Baptist,7Painting index, nos. 393 and 394. Editors’ note: Klein 1994a: 101–3. together with the 14th-century Netherlandish chest panel painted on walnut with Scenes from the Life of the Virgin.8Painting index, no. 422. For the same reasons, we can add to these three paintings the two Umbrian spruce panels attributed to the Pinturicchio School, with The Judgement of Daniel and The Judgement of Solomon;9Painting index, nos. 368 and 369. the two panels in maritime pine from the 14th- and 15th-century Aragonese School, showing Scenes from the Passion and St Martin; and one made from the same wood from the 15th-century Catalan School, representing Christ among the Doctors.10New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art), School of the Master of St George, Jesus among the Doctors (Painting index, no. 832A). The anomalies are therefore limited to eight panels out of almost eleven hundred examined – a finding that lends almost absolute weight to the rule that emerges from the statistics.

Before we can categorise a panel as an anomaly, further research is needed to determine the circumstances under which the work in question was executed. A painting executed on walnut in Flanders would be anomalous if the support were constructed in situ, but not if it were a panel from a piece of furniture. The early Netherlandish chest panel, for instance, might have been painted some time after the object itself was produced. The chest could have been made abroad and then decorated in Flanders, which would explain the presence of walnut in a northern school.11Editors’ note: Walnut was often used for sculptures at this time region; P. Klein, personal communication, 2014.

Similar research is required for the two spruce panels found in the Umbrian School. Comparison between the historical map of Italy and the outline of Italian vegetation shows that the peninsular Italian schools had a certain range of woods from which to choose, thanks to differences in altitude, but that they could not have sourced spruce or larch locally.12Editors’ note: Castelli et al. 1997: 162–74; Ciatti et al. 1999. Continental Italy, by contrast, particularly in the north, did produce both of these woods. Larch dominates at high altitudes, but spruce is found throughout. Spruce in Italy could, therefore, only have come from the northern region. Similarly, maritime pine is unknown in Aragonese and Catalan schools, and so its use places the panels on the country’s Atlantic slopes.

We can, of course, also imagine the occasional use of boards originating from outside the region, from packing cases, say, by an artist short of funds. Another, more plausible possibility would be a painting done abroad by an itinerant artist who later returned with it to his country of origin. Whatever the case, resolving the problems raised by anomalies of this kind is beyond the scope of this study.

Application of the rule: dominant and characteristic species

The rule we have inferred – which asserts itself with considerable rigour, and which we might hope to have some practical use – may be supplemented by another, very important one. Painters used local wood species, and foreign woods certainly represent an anomaly.13Editors’ note: Since Marette’s publication, research into the timber trade and dendroprovenancing has demonstrated a huge and important trade in Baltic oak that entered northern Europe, England and France via Hanseatic trading stations; see Streeton and Wadum 2012: 86‒91. However, not all the local wood types were used and certain varieties common to several regions feature in one school but not another, highlighting the dominant species and the characteristic species, from which it seems we can draw a valid conclusion.

French School

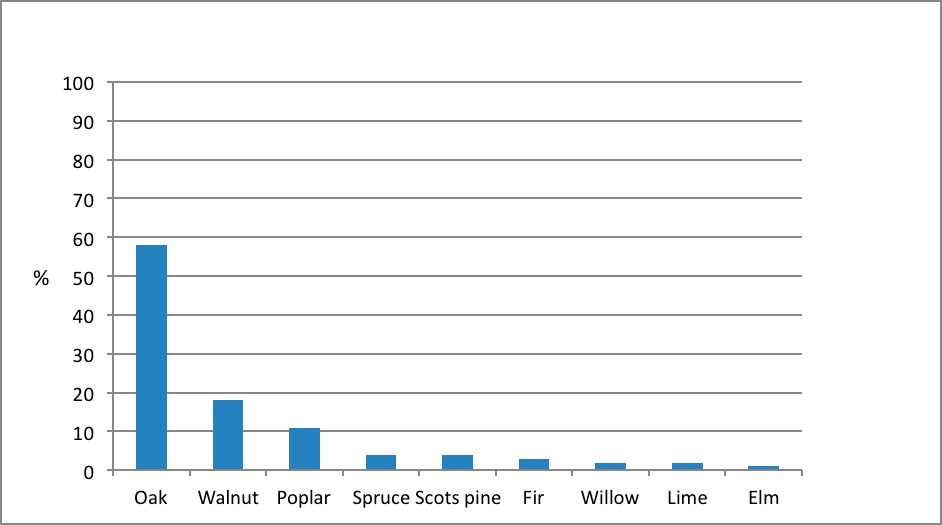

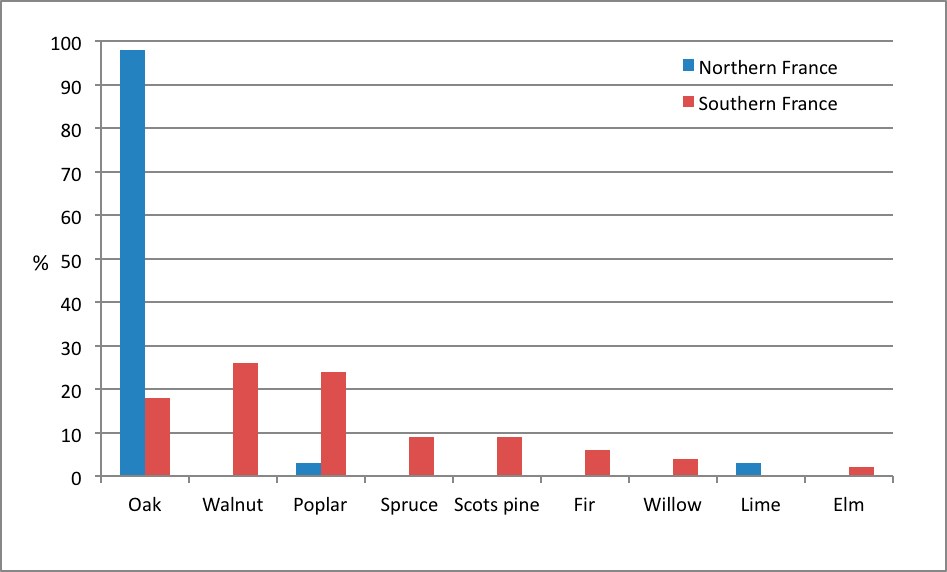

Oak accounts for 57% of the wood used in the panels we examined, walnut for 17.8%, poplar 11.2%, Scots pine and spruce 4%, lime and willow 1.3% and elm 0.7%. It is useful, however, to divide France into two regions, one to the north and one to the south of the Loire, including Burgundy.

North of the Loire, oak represents 96% of the wood used in the panels, whereas in the south, it only accounts for 18.7%; walnut, by contrast, which is absent in the north, accounts for 26.4% of the total in the south, poplar for 25%, Scots pine and spruce 9.4%, fir14The use of fir is unusual in France and places the panels in the southeast of the country. 6.2%, willow 3.1% and elm 1.6%. Table 13 summarises this distribution.

Table 13 Distribution of species in France.

Graph comparing the schools north and south of the Loire.

We find that oak is utilised primarily in the northern schools,15Editors’ note: Wadum 1998a: 149–77. that walnut, which is completely absent north of the Loire, is the most frequently used wood south of that river; that the uniformity of species in the north contrasts with the diversity in the south; that lime is an exception; and that among the wood types present in the country and used as painting panels by other schools, chestnut was not employed in France.16It nevertheless exists in the indicated areas, which correspond with mountain forests, but only where there are siliceous soils: on the periphery of the Massif Central, and beyond the threshold of the Poitou region as far as the Paris Basin (cf. Chapter 3, ‘Attempted reconstruction of forest vegetation in Europe prior to the 18th century’).

Lime, elm and willow are, however, exceptions rather than anomalies. Lime did exist in the hardwood forests of the hills and low mountains, accompanied by hornbeam, oak and ash, to the north of Paris and in eastern Picardy. In 1467, the statutes of the Paris woodturners mention it in the following terms: ‘The master and journeyman turners of Paris may utilise and employ the oakwood they are accustomed to use ... and may make no use of the said woods, such as beech, lime and aspen, and other woods belonging to the said trades.’17Archives Nationales, Y7, fol. 78. ‘Que les maîtres et ouvriers tourneurs à Paris puissent mectre et employer le bois merrien dont ilz ont accoustume a user … et faire aucunes besongnes de leurd. bois comme de hestre, de tilleul, et tramble et autres bois appartenant aud. métiers.’ Editors’ note: Imported Baltic oak may have been available in Paris, and certainly oak panels manufactured in Antwerp were available there in the early 17th century; see Wadum 1998a.

Lime is also mentioned in the building accounts of the castles of the counts of Artois in 1345: ‘To Huard the joiner ... for three hundred and a half limewood boards.’18Gay 1928, I: 164. ‘A Huard le hugier ... pour trois cents et demi de late de tilleul.’

In a similar way, the presence of elm and willow south of the Loire is unusual but not anomalous among panels of the 14th- and 15th-century Provence and Avignon schools.19Elm: Mary Magdalene Preaching at Marseille, Marseille (Musée du Vieux-Marseille), Painting index, no. 434; willow: Thouzon Altarpiece, Musée du Louvre (Painting index, nos. 996–997). These trees, which grow in the vicinity of poplars, were more likely to be found in the valleys, especially that of the Rhône. An extract from the accounts of the dukes of Burgundy, dated 1 November 1378, mentions the sale of an elm: ‘Brought down by the wind on the road to Saint-Broing-les-Mornes at Moitron (Côte-d’Or).’20Prost 1902–1913, II: no. 384: ‘Cheu par force de vent sur le chemin de Saint-Broing-les-Mornes, à Moitron (Côte-d’Or).’ Elm similarly figures in the accounts of the Chartreuse at Dijon, among the timber used to make a floor.21C. Monget, La Chartreuse de Dijon, p. 309: ‘la façon de ce plancher’. We are indebted to Charles Sterling for the abundant documentation borrowed from Cyprien Monget’s La Chartreuse de Dijon, which is cited throughout this book. We are sincerely grateful to him.

Oak, which is common throughout France, is used considerably less frequently south of the Loire, but is still a normal wood species there, albeit a much more frequent one in Burgundy, Bourbonnais and Touraine than in Provence. The number of oak panels progressively decreases the further south one goes. The Loire, Bourbonnais and Burgundy regions represent a total of twenty-two oak panels, compared to seven in Provence. Oak was very common in the Rhône valley in the Middle Ages, whereas in our own time it has virtually disappeared.

Although it was used less frequently in the south of France, oak therefore features everywhere in French painting. However, it would have been very interesting had we been able to identify the different types of oak, which vary from one region to another. Deciduous oak is present only in the northern half of France, while holm oak and evergreen cork oak also appear in the Aquitaine Basin and the Mediterranean region.22Information provided by Mr. Jacquiot and included in this study with his kind permission. Consequently, distinguishing between these varieties would have allowed us to verify whether or not the wood of these panels matches the natural surroundings of each school. As we noted at the beginning of this study, however, it is only possible to do so by examining small samples under the microscope.

Lastly, Spruce and Scots pine are present in northeast Provence at different altitudes. It is therefore normal for panels belonging to the Provence School, specifically those of the eastern, Nice School,23Painting index, nos. 362–367 (spruce) and 927–930 (Scots pine). to be made from these woods. Scots pine is also possible for the Rhône valley, as it is found in the Lyon region.24Rhône School, The Coronation of the Virgin and The Death of the Virgin, Lyon (Musée des Beaux-Arts), Painting index, nos. 931 and 932. Spruce by contrast is not found there and was not used by this school. It is not found in the Pyrenees or Massif Central either, although it does occur in the Ain region, close to the Jura, and in Burgundy.

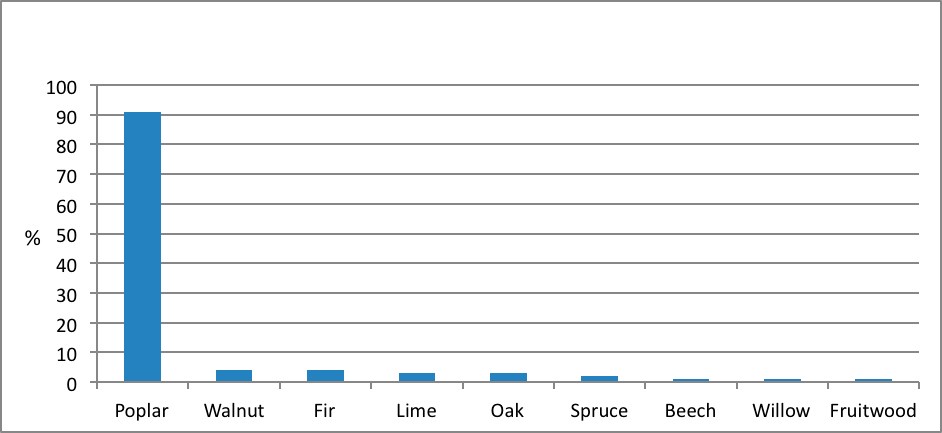

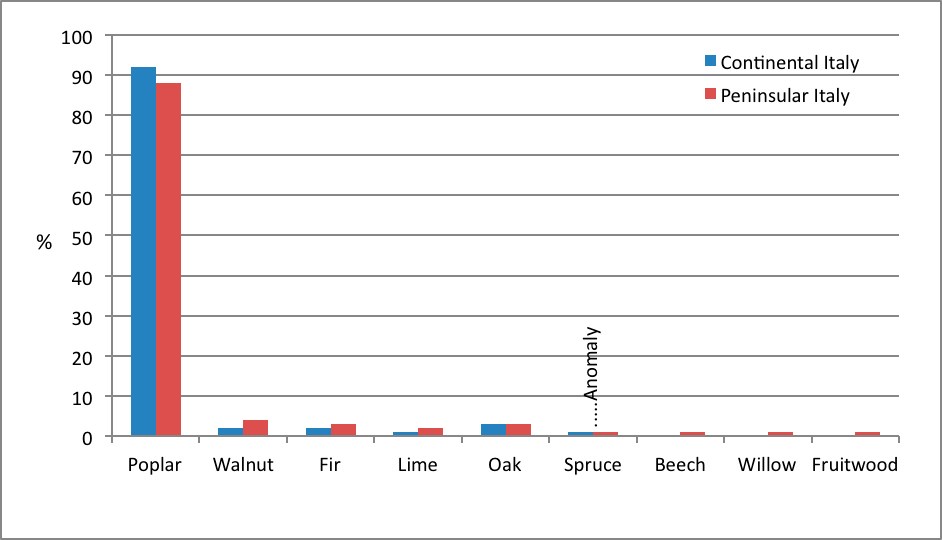

Italian School

We find six varieties of wood among the 125 panels associated with continental Italy, compared to eight varieties for the 220 panels from peninsular Italy, although the vast majority of panels from this part of the country are poplar. Despite the greater diversity of species, poplar accounts for 89.1% of panels in peninsular Italy compared to 91.2% in continental Italy.25Editors’ note: Klein and Bauch 1990: 85–91; Bruzzone 2007/2008. Walnut, oak and fir are equal, each representing 2.4% of the woods in the north, compared to 3.2% walnut, 0.9% oak and 2.7% fir in peninsular Italy. Finally, lime and spruce contend for last place in the north, as do beech, willow and fruitwood (most likely pear) in the peninsula. These breakdowns are shown Table 14.

Table 14 Distribution of species in Italy.

Graph comparing the schools of continental and peninsular Italy.

In summary, poplar accounts for the overwhelming majority of panels in Italy, with the other varieties following very far behind. So overwhelming, in fact, that we can safely state that poplar is the characteristic wood26Editors’ note: See Bisacca and Castelli 2012. for the Italian schools of painting, just as oak characterises the Dutch and Flemish schools.

Walnut, which features in the second rank of species, comes a very long way behind, followed immediately by fir and then by lime and oak. Each of these species holds only an extremely subordinate place in the Italian School. Walnut is more common among the peninsular schools, although the percentage remains low. Spruce, which is absent from the peninsula, accounts for a small percentage in continental Italy, as do beech, willow and fruitwood. The three latter species are characteristic of the peninsular schools. The rarity of these species makes them unusual, but not anomalous. Moreover, despite the subordinate place they occupy, they are nonetheless wholly aboriginal. Northern Italy is covered by a forest composed of beech (Ligurian Alps, up to 1400 m), fir, spruce and larch (same region, above 1400 m). This huge forest caps northern Italy, and so it is normal for spruce and fir to be present in the Venetian School and fir in that of Lombardy.

Beech is found up to 1400 m in both the Ligurian Alps and the Apennines. The beech panel from the Bolognese School,27Annibale Carracci, The Infant Hercules Strangling the Serpents, Musée du Louvre (Painting index, no. 379). close to the Apennines, is therefore also entirely logical. The presence of willow is normal more or less everywhere, as is that of poplar, and so the willow panel found in the 15th-century Florentine School28Biagio d’Antonio, The Virgin with the Curtain, Lyon (Painting index, no. 998). may not be deemed an anomaly, even though it is unique of its kind in Italy. Walnut is found dispersed throughout Italy. The species originated in a temperate climate and it prefers warmth and sunshine, so Italy must have suited it, as must the south of France. The Venetian and Ferrara schools, both of which used walnut, will certainly have found it locally. Oak is very common in Italy. It was found throughout the country’s territory during this period, which means that all varieties of oak could be procured around the Po valley or in one of Italy’s mountain regions.29Localisation of the different varieties of oak to particular regions would have given us an interesting method of attributing the panels to a specific school. As we have already noted for France, however, distinguishing between oak types in this way was not possible.

Lastly, lime is a local wood for the schools of Emilia30Emilia, triptych, centre, right wing (Painting index, nos. 1049 and 1050); Garofalo, The Christ Child Sleeping, Musée du Louvre (Painting index, no. 1051). and Ferrara. The forest of the Po valley, where we find this wood, covers Emilia, part of the Veneto region, and the duchies of Modena, Parma and Milan. The 15th-century Florentine School, by contrast, represented (in this study) by one limewood panel,31Lorenzo di Credi, Noli me tangere, Musée du Louvre (Painting index, no. 1052). is located farther away from that region.

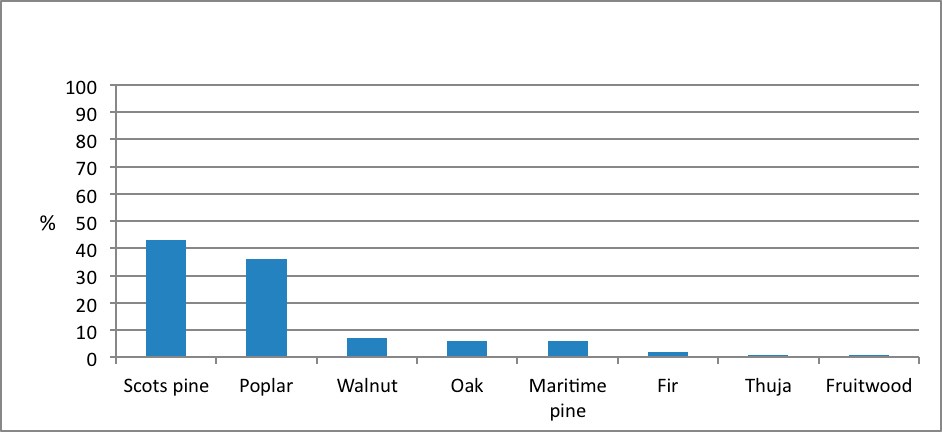

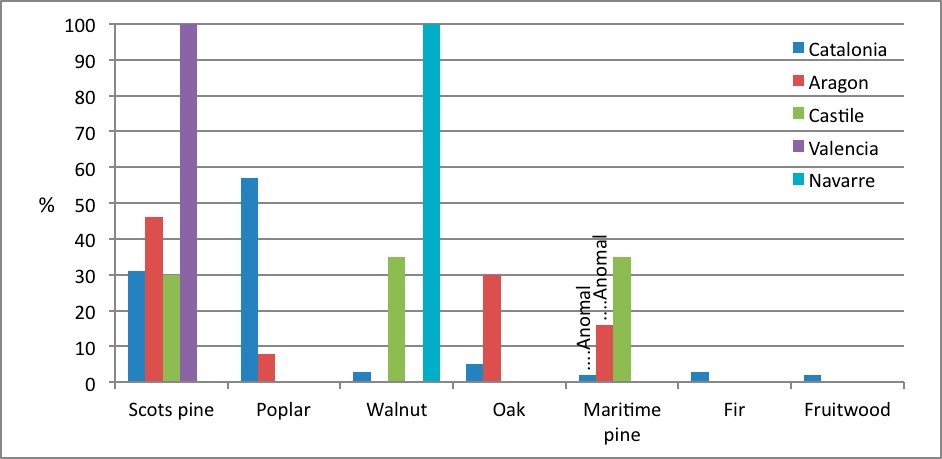

Spanish School

Of the 168 panels comprising the Spanish schools of Catalonia, Castile, Aragon, Valencia and Navarre, 42.1% are made of Scots pine and 35.5% of poplar. These two species, which between them appear to account for most of the Spanish School’s panels, are not in fact employed uniformly in all those schools, except that of Catalonia, where 57.6% of panels are made of poplar and 32% of Scots pine. The Catalan School accounts for 98.2% of the poplar panels used by all the Spanish schools and 47% of the panels in Scots pine. According to Gonzalez Vasquez, the black and white poplar – i.e. the indigenous species – occurs in the valleys of northern Spain.32Gonzalez Vasquez 1947: 346. There is no further use of poplar in Spain. Located in Catalonia, it cannot be considered as the characteristic wood of the Spanish schools in general, unlike Scots pine, which is used in Castile, Aragon, and Valencia and accounts for 42.1% of Spanish panels. It is therefore common to all the schools and this sporadic species is indeed found more or less throughout Spain. Rubner locates it more particularly to below the fir zone in the eastern foothills of the Spanish Pyrenees,33Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 211. which corresponds with the schools of painting that made particular use of it.

In the case of the Navarre School, our statistics relate to too small a number of paintings for us to be able to draw any valid conclusions. Walnut accounts for 7.8% of the panels in Castile, Navarre and Catalonia; oak, located in Catalonia and Aragon, is equal to maritime pine in Castile and Aragon. These two woods each represent 6% of panels in the Spanish School. Finally, fir34Gonzalez Vasquez 1947: 346. and thuja only account for 1.8%.

Table 15 Distribution of species in Spain.

Graph comparing the schools of Catalonia, Aragon, Castile, Valencia and Navarre.

In summary, the main features of the Spanish School are the concentration of poplar in Catalonia and the presence of Scots pine, maritime pine and thuja. The two latter wood types are used exclusively in Spain.

Forestation patterns in these regions perfectly match the localisation of the different wood types in the schools of painting where they were employed. The use of poplar, a secondary species alongside dominant varieties such as Scots pine, is perfectly in keeping with its presence in the large valley of the Ebro river, which crosses Catalonia.

The fir wood panel identified in the Catalan school of Girona is likewise appropriate for this town close to the coniferous forest of the Pyrenees, in which fir and Corsican pine grow among Scots pine.35Fir has only been found in the mountains since the deforestation that occurred during the Arab occupation of the 7th to the 13th century. The Mediterranean zone of downy, holm and pedunculate oak also encompasses the Catalan and Aragonese schools, in which these woods were used.

There is no maritime pine in Spain, by contrast, except in the northern Atlantic sector. The presence of this species in the Avila School, where it was used for the Altarpiece now in the Musée de Cluny,36The Master of Riofrió, altarpiece, seven panels (Painting index, nos. 826–832). is explicable, but it is anomalous in the Aragonese37Aragonese School, Barcelona, Scenes from the Passion of Christ (Painting index, no. 824); St Martin (Painting index, no. 825). and Catalan schools.38Catalan School, New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art), Jesus among the Doctors (Painting index, no. 832A).

Reading Rubner’s map39Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 219b, no. 10. (Interpretation of Rubner’s map by Silvy-Leligois.) does indeed enable us to localise maritime pine to the immediate north of Avila, but it does not show the species in the Aragon area. Maritime pine is found north of San Sebastian, level with the Bay of Biscay, but this region is still too far away from Aragon or Catalonia to explain the panels attributed to these two schools. Pine in Catalonia could be either black or Aleppo pine.

Spain’s warm climate – like that of Italy and the south of France – suits the walnut. The tree grows in a diffuse pattern, favouring temperate regions. Its presence in the schools of Catalonia, Castile and Navarre,40Gonzalez Vasquez 1947: 360. regions with a more uniform climate than the rest of the country, is therefore entirely natural.

Lastly, thuja appears here as a painting support for the first time.41Spanish School, 16th century, The Head of Christ, Lisbon (Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga), Painting index, no. 1053. Schmucker42Schmucker 1942: map 50. situates this species in the south of the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa while Boudy locates it more specifically in the Cartagena region.43Boudy 1950: 706–7. This enables the panel currently assigned to the 16th-century Spanish School to be localised more precisely.

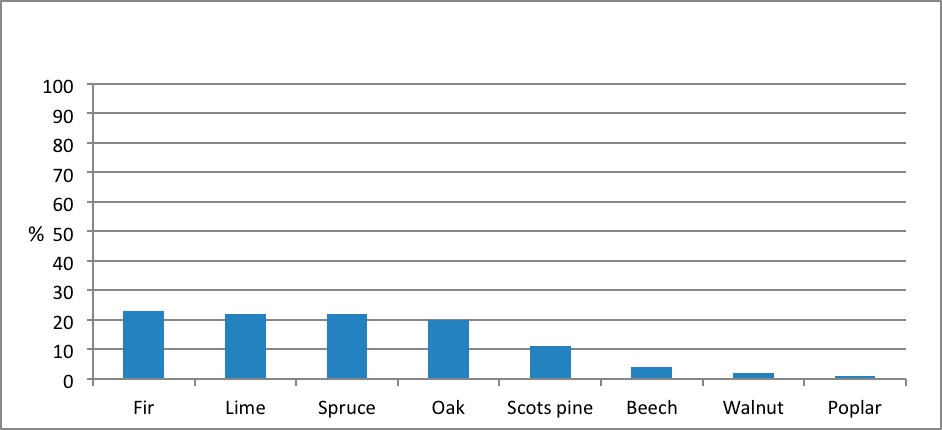

German School

Fir, spruce, lime, and oak together account for 84.8% of the panels used by the German schools of painting. Each of the four varieties takes a share of 20–21.8%, making the distribution of dominant species more uniform in this school. Walnut and poplar do not appear at all, and beech is very rare.44Editors’ note: Beech was found often in the Cranach workshop; Klein and Bauch 1983. Walnut was found in the Cologne School e.g. Stefan Lochner (ca. 1400/1410–1451). For an updated view see Heydenreich 2007. Softwoods dominate the German School, with fir, spruce, stone pine (in the Alps) and Scots pine accounting for 55% of the total.

Table 16 Distribution of species in Germany.

Lime, which represents just under 22% of the panels, was used in all the German schools of the forest region in which it is found.45It is useful to distinguish in the Upper Rhine region between the rich valleys (around Lake Constance) and the mountainous regions, where lime has been eradicated. The Upper Rhine School that did use it was most likely that of the Constance region. Editors’ note: See Heydenreich 2007 and Klein 2012, among others. It is not present, conversely, in the schools of Cologne, Westphalia and Tyrol, which lie outside that region. This fact is especially revealing. The Franconian and Saxon schools,46Franconia (Painting index, nos. 1014 and 1018) and Saxony (Painting index, nos. 1039–1042). which did use lime, sourced it locally. According to Rubner, mixed oak, beech and hornbeam forests at moist locations in Franconia and Saxony do indeed include a high proportion of lime.47Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 86.

Beech, like lime, is found almost exclusively in the German schools of painting. The species occurs in the forests of the Baltic coast and also grows throughout most of the territory, in the vicinity of either oak or fir. The Bavarian School, which used it, as well as the southern and northern Saxon schools, sourced it locally.48The limited use of this wood as a support for paintings in a country where it is more or less ubiquitous no doubt reflects its pronounced shrinkage (see Cf. Chapter 2, ‘Wood technology’.). Oak, which is found throughout Germany, was nevertheless only used by the western schools: Swabia, Upper Rhine, Lower Rhine and Westphalia.

Lastly, it should be noted that walnut, although very rare in Germany, was found sporadically in the Rhine valley, from the Swiss Plateau through to the upper valley.49Cf. Chapter 3, ‘Attempted reconstruction of forest vegetation in Europe prior to the 18th century’. As in the other countries, walnut prefers temperate regions. Its use as a support in the Rhine region is therefore entirely natural.

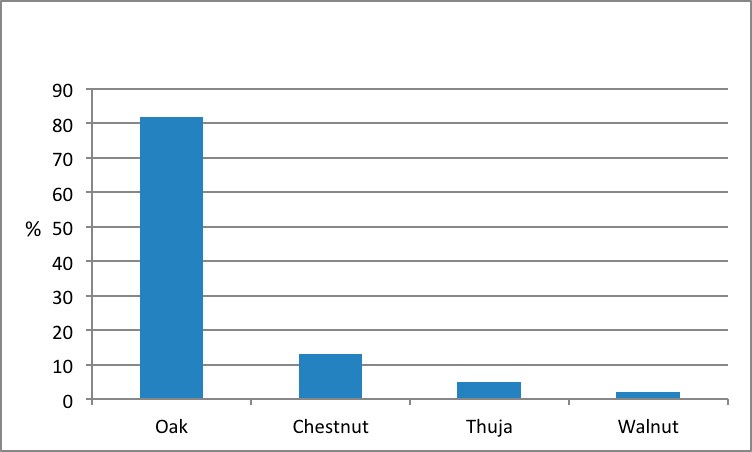

Portuguese School

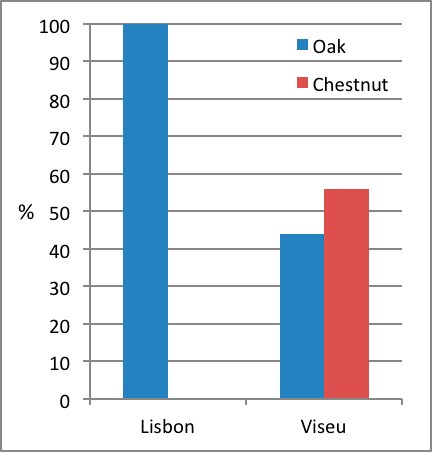

Oak is by far the most common species of wood used to construct panels in Portuguese painting. The supports in question break down into almost 82% oak and 18% chestnut, thuja, and walnut. Chestnut alone accounts for 12.5% of panels, thuja for 4.5%, and walnut 1%. The appearance of chestnut in the Portuguese School is a novelty. This wood – which is not used in the other schools, even though it is present in Germany, France, Italy and Spain50According to Rubner, chestnut is found in the indicated areas, which correspond with the mountain forests, but only in areas with siliceous soil (Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 209). – may be classified as the characteristic species of this school, just as thuja is characteristic of the schools of the southern Iberian Peninsula.

Although oak grows throughout Portugal and is the national tree, this does not make it the only dominant species for the Portuguese School, as it is in Dutch and Flemish painting: chestnut and thuja also feature, giving the Portuguese School a character genuinely of its own.51Editors’ note: Most of the oak that was used in the Portuguese School was imported from the Baltic region. Klein and Esteues 2001.

The use of chestnut by the Viseu School corresponds perfectly with the presence of the species in the surrounding mountains. The Lisbon School used oak, while the Viseu School also employed chestnut, found in abundance locally. Use of local wood is the norm here, as elsewhere. Similarly, thuja, located in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, was bound to be used exclusively in Portugal and Spain.

Table 17 Distribution of species in Portugal.

Graph comparing the schools of Lisbon and Viseu.

English School

The variety of Portugal’s vegetation contrasts with the uniformity of that in the British Isles. Marcel Schweitzer52Marcel Schweitzer, ‘Aperçu géographique sur le Portugal’, published in Le Guide bleu, Paris 1953. has drawn our attention to the following fact: ‘2,700 species in Portugal compared to 1,848 in Britain, for a territory three and a half times larger’. One only needs to look at the map (Fig. 46): an overabundance of oak mixed with ash throughout the country; a few beech trees in the southeast; no fir, as we noted in the chapter on anomalies; a little Scots pine in the far northeast of Scotland – these were the wood varieties painters could find locally.53Editors’ note: Fraiture 2009; Tyers 2010.

A study of this school would have required a minimum sample size, which it was not possible for us to achieve. The overabundance of oaks throughout the territory suggests that this wood was the one most commonly used for paintings, as we know it to have been in English woodworking until the 17th century.54It was indeed from around this period that use of walnut spread throughout Britain. Although the species was introduced during the Roman occupation, the first precise trace of regular cultivation in this country dates from 1562. Walnut did not begin to be used in English furniture-making until the new style that arose in the country around the mid-17th century (Macquoid 1904–08, II: 5–6). The single panel studied from this school was made up of twenty oak planks.55English School, 13th century, The Life of the Virgin, Paris (Musée de Cluny), Painting index, no. 55; Tyers 2010.

Southern and Northern Netherlandish schools

The simplicity of the vegetation in these two regions and its similarity to that of the British Isles leads us to substantially the same conclusions: beech in greater quantity, a few lime trees and the presence of spruce in mixed forests, alongside beech; a complete absence of fir and walnut throughout the region and the presence of poplars in the Northern Netherlands, along the valleys of the Rhine and its tributaries. The map showing the forest vegetation (Fig. 44) is particularly striking. We find a predominance of oak in the two countries. All the Northern and Southern Netherlandish panels were in oak, apart from three in walnut, which were among the anomalies already identified.56Editors’ note: Beech, fir and pear could also be identified; Wadum 1998a: 149–77. Recent work clarifies and contradicts these conclusions; see Fraiture 2009; Klein 2012.

Conclusion

Comparison of the statistical results set out above with the forest and historical maps allows us to infer the rule that painters exclusively used local wood to construct their panels.57Editors’ note: Wazny 1992: 331–3. This rule is borne out with such rigour that a panel painted on a wood foreign to its region has to be considered an anomaly. Utilisation of spruce in Spain and peninsular Italy; fir in England and Flanders; walnut in northern France, Flanders, and Holland; beech in central and southern Spain; Scots pine beyond Spain’s Atlantic coast; and lastly, thuja beyond the south of the Iberian Peninsula is therefore anomalous.

Analysis of the statistics also reveals the dominant species and characteristic species of each school, from which we can draw conclusions. Although the same species are found in many schools, they were not used indiscriminately. The more systematic use of some of them represents a constant in each school, from which valid insights may emerge. For instance, oak, which is widespread throughout Europe, was the only wood used by the northern schools of France, the Northern and Southern Netherlandish schools, and may thus be viewed as the characteristic wood species of northern schools.58Editors’ note: Wazny 2002: 313–20.

The overwhelming predominance of poplar in Italy makes it the characteristic wood of the Italian schools, while sharing that status with Scots pine for the Spanish School. Lime, which is used primarily in the south and southwest of Germany, is the characteristic wood of the Rhine schools and, it would appear, of the Austrian and Bohemian schools, subject to verification in the latter two cases on a larger number of panels. What most characterises the German School, however, is the extremely widespread use of softwoods, and also the employment of beech, which is limited to this school.

Walnut is primarily associated with the French schools south of the Loire, where it is found much more frequently than anywhere else in Europe. Although chestnut is native to all the countries of Europe, it is the characteristic wood of the Viseu School in Portugal, which is the only one to use it.

Table 18 Relative importance by school of the main species employed.

The conclusions of this study might justify specific research for a number of paintings, regarding the place and conditions in which they were produced. The results of that research could challenge certain attributions or, on the contrary, lend weight to them.59To illustrate, we will pick paintings at random from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Museum in New York – Christ Carrying the Cross from the Northern French School, for instance, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Painting index, no. 187A). The attribution of this painting is confirmed by the use of ‘deciduous oak’ for the support, which is only found in the northern half of France (cf. Part I, Chapter 4). Similarly, this species of oak – found as the support of the Burgundian School Portrait of a Young Man in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Painting index, no. 173A) and the French Portrait of a Man with a Hawk in the Brooklyn Museum (Painting index, 133A) – orientates these panels toward a northern school. In another instance, the use of maritime pine confirms the attribution to the Spanish School of the same museum’s Jesus Among the Doctors (Painting index, no. 832A), and reaffirms the impossibility of the earlier attribution of this painting to Jean Malouel. Its attribution to the Catalan School would, however, constitute an anomaly. Lastly, the use of a spruce support for St Margaret and St Catherine at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Painting index, no. 360A) suggests that the panel is more likely to have originated in a southern German School (Swabia, Bavaria, Tyrol) than in France. The fact that certain types of wood could not be found anywhere in a particular country, combined with the absolute certainty that native woods were used locally, will rule out certain schools in favour of others. What is more, the systematic use of a particular type of wood by a particular school ought to allow a panel to be linked more firmly with one school than another.

In summary, we believe that these results will systematically enable art historians to narrow down attributions and in some cases to challenge or confirm them. They are not sufficient in themselves, however, to supply an attribution.60Editors’ note: The complex and vast trade in timber between the 14th and the 17th century was not fully understood in the 1960s. As has been demonstrated by dendrochronological studies during the past four decades, the situation described by Marette should be significantly nuanced – although her main conclusion may serve as a first guideline.

2 Les Primitifs flamands. I: Corpus de la peinture des anciens Pays-Bas méridionaux au XVe siècle; II: Répertoire des peintres flamands des XVe et XVIe siècles, Antwerp 1952–1954, 3 vols. Editors’ note: See other relevant publications from the Centre for the Study of the Flemish Primitives (CSFP) in Brussels (three series : ‘Repertory of Flemish paintings of the fifteenth and sixteenth century’; ‘Corpus of fifteenth century painting in the Southern Netherlands’; ‘Contributions to the study of the Flemish Primitives’), which give detailed descriptions, photographs and sometimes X-radiographic images of Flemish panel paintings in various museums worldwide (note that many of these publications have been scanned and will be available online on the website of the CSFP (http://xv.kikirpa/en/homepage.htm) in 2015. In the ‘Repertory’ series, on collections in Spain, see Lavalleye 1953, 1958; on collections in Italy, see Carandente 1968; on collections in the former Czechoslovakia, see Vacková and Comblen-Sonkes 1985; on collections in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais, see Heck 2005; on public collections in Liège, see Allart 2008. Several volumes in the ‘Contributions’ series are relevant to the study of panel supports: on the Ghent Altarpiece, see Coremans 1953; on Pre-Eyckian panel painting, see Deneffe et al. 2009; on Albrecht Bouts, see Henderiks 2011. All twenty-two ‘Corpus’ volumes are useful for their technical descriptions and illustrations – each is dedicated to a specific collection or collections. Other relevant ‘Corpus’ publications published thereafter: on the Groeningemuseum, see Janssens de Bisthoven 1983; on the Sabauda Gallery of Turin, see Aru and De Geradon 1952; on the National Gallery, London, see Davies 1971; for New England Museums (Boston, Cambridge, Hartford, New Haven, Williamstown and Worcester), see Eisler 1961; on the Musée du Louvre, Paris, see Adhémar 1962, Comblen-Sonkes 1996 and Lorentz and Comblen-Sonkes 2001; on the Royal Chapel of Grenada, see Van Schoute 1963; on the Ducal Palace of Urbino, see Lavalleye 1964; on the Hermitage Museum, see Loewinson-Lessing and Nicouline 1965; on museums in Poland, see Bialostocki 1966; on the Cathedral of Palencia, see Vandevivere 1967; on the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, see Hoff and Davies 1971; on the Hôtel-Dieu of Beaune, see Veronée-Verhaegen 1973; on the Musée des Beaux-Arts of Dijon, see Comblen-Sonkes and Veronée-Verhaegen 1987; on the Musées de l’Institut de France – Musée Jacquemart-André, Musée Marmottan and Musée Condé – see Comblen-Sonkes 1988; on the National Museum of Fine Art in Lisbon, see Lievens-De Waegh 1991; on the collegiate church of Saint Peter, Louvain, see Comblen-Sonkes 1996; on the Mayer van den Bergh Museum, Antwerp, see Mund et al. 2003; on the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lille, see Châtelet and Goetghebeur 2006; on the Los Angeles Museum of Art, see Wolfthal and Metzger 2014. »

3 Editors’ note: Painters’ contracts from this region, primarily from the 15th century, are published in Dijkstra 1990. »

4 Editors’ note: Research subsequent to Marette’s study has shown this not to be the case. Indeed, dendrochronological studies have proved that most of the wood used in northern European panel painting in the 15th and 16th centuries was imported by sea from the Baltic region. See Streeton and Wadum 2012: 86‒91; Streeton 2013: 105‒22; Bonde 1992: 53–5; Klein et al. 1987b: 51– 4; Baillic 1984: 371–93. »

5 Les Primitifs flamands (1952–1954), I, parts 1–4, nos. 1–15; part 5, nos. 16 and 20; parts 6–13, nos. 21–63; II, nos. 1–50. »

6 Editors’ note: Research has proved that this conclusion should be strongly modified. Indeed, dendrochronological studies have confirmed that most of the wood used in northern European panel painting in the 15th and 16th centuries was imported by sea from the Baltic region. See Streeton and Wadum 2012: 86‒91; Streeton 2013: 105‒22; Bonde 1992: 53–5; Klein et al. 1987b: 51–4; Baillic 1984: 371–93. »

10 New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art), School of the Master of St George, Jesus among the Doctors (Painting index, no. 832A). »

11 Editors’ note: Walnut was often used for sculptures at this time region; P. Klein, personal communication, 2014. »

13 Editors’ note: Since Marette’s publication, research into the timber trade and dendroprovenancing has demonstrated a huge and important trade in Baltic oak that entered northern Europe, England and France via Hanseatic trading stations; see Streeton and Wadum 2012: 86‒91. »

14 The use of fir is unusual in France and places the panels in the southeast of the country. »

16 It nevertheless exists in the indicated areas, which correspond with mountain forests, but only where there are siliceous soils: on the periphery of the Massif Central, and beyond the threshold of the Poitou region as far as the Paris Basin (cf. Chapter 3, ‘Attempted reconstruction of forest vegetation in Europe prior to the 18th century’). »

17 Archives Nationales, Y7, fol. 78. ‘Que les maîtres et ouvriers tourneurs à Paris puissent mectre et employer le bois merrien dont ilz ont accoustume a user … et faire aucunes besongnes de leurd. bois comme de hestre, de tilleul, et tramble et autres bois appartenant aud. métiers.’ Editors’ note: Imported Baltic oak may have been available in Paris, and certainly oak panels manufactured in Antwerp were available there in the early 17th century; see Wadum 1998a. »

18 Gay 1928, I: 164. ‘A Huard le hugier ... pour trois cents et demi de late de tilleul.’ »

19 Elm: Mary Magdalene Preaching at Marseille, Marseille (Musée du Vieux-Marseille), Painting index, no. 434; willow: Thouzon Altarpiece, Musée du Louvre (Painting index, nos. 996–997). »

20 Prost 1902–1913, II: no. 384: ‘Cheu par force de vent sur le chemin de Saint-Broing-les-Mornes, à Moitron (Côte-d’Or).’ »

21 C. Monget, La Chartreuse de Dijon, p. 309: ‘la façon de ce plancher’. We are indebted to Charles Sterling for the abundant documentation borrowed from Cyprien Monget’s La Chartreuse de Dijon, which is cited throughout this book. We are sincerely grateful to him. »

22 Information provided by Mr. Jacquiot and included in this study with his kind permission. »

24 Rhône School, The Coronation of the Virgin and The Death of the Virgin, Lyon (Musée des Beaux-Arts), Painting index, nos. 931 and 932. »

27 Annibale Carracci, The Infant Hercules Strangling the Serpents, Musée du Louvre (Painting index, no. 379). »

29 Localisation of the different varieties of oak to particular regions would have given us an interesting method of attributing the panels to a specific school. As we have already noted for France, however, distinguishing between oak types in this way was not possible. »

30 Emilia, triptych, centre, right wing (Painting index, nos. 1049 and 1050); Garofalo, The Christ Child Sleeping, Musée du Louvre (Painting index, no. 1051). »

32 Gonzalez Vasquez 1947: 346. »

33 Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 211. »

34 Gonzalez Vasquez 1947: 346. »

35 Fir has only been found in the mountains since the deforestation that occurred during the Arab occupation of the 7th to the 13th century. »

37 Aragonese School, Barcelona, Scenes from the Passion of Christ (Painting index, no. 824); St Martin (Painting index, no. 825). »

38 Catalan School, New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art), Jesus among the Doctors (Painting index, no. 832A). »

39 Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 219b, no. 10. (Interpretation of Rubner’s map by Silvy-Leligois.) »

40 Gonzalez Vasquez 1947: 360. »

41 Spanish School, 16th century, The Head of Christ, Lisbon (Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga), Painting index, no. 1053. »

42 Schmucker 1942: map 50. »

43 Boudy 1950: 706–7. »

44 Editors’ note: Beech was found often in the Cranach workshop; Klein and Bauch 1983. Walnut was found in the Cologne School e.g. Stefan Lochner (ca. 1400/1410–1451). For an updated view see Heydenreich 2007. »

45 It is useful to distinguish in the Upper Rhine region between the rich valleys (around Lake Constance) and the mountainous regions, where lime has been eradicated. The Upper Rhine School that did use it was most likely that of the Constance region. Editors’ note: See Heydenreich 2007 and Klein 2012, among others. »

47 Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 86. »

48 The limited use of this wood as a support for paintings in a country where it is more or less ubiquitous no doubt reflects its pronounced shrinkage (see Cf. Chapter 2, ‘Wood technology’.). »

49 Cf. Chapter 3, ‘Attempted reconstruction of forest vegetation in Europe prior to the 18th century’. »

50 According to Rubner, chestnut is found in the indicated areas, which correspond with the mountain forests, but only in areas with siliceous soil (Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 209). »

51 Editors’ note: Most of the oak that was used in the Portuguese School was imported from the Baltic region. Klein and Esteues 2001. »

52 Marcel Schweitzer, ‘Aperçu géographique sur le Portugal’, published in Le Guide bleu, Paris 1953. »

54 It was indeed from around this period that use of walnut spread throughout Britain. Although the species was introduced during the Roman occupation, the first precise trace of regular cultivation in this country dates from 1562. Walnut did not begin to be used in English furniture-making until the new style that arose in the country around the mid-17th century (Macquoid 1904–08, II: 5–6). »

55 English School, 13th century, The Life of the Virgin, Paris (Musée de Cluny), Painting index, no. 55; Tyers 2010. »

56 Editors’ note: Beech, fir and pear could also be identified; Wadum 1998a: 149–77. Recent work clarifies and contradicts these conclusions; see Fraiture 2009; Klein 2012. »

59 To illustrate, we will pick paintings at random from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Museum in New York – Christ Carrying the Cross from the Northern French School, for instance, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Painting index, no. 187A). The attribution of this painting is confirmed by the use of ‘deciduous oak’ for the support, which is only found in the northern half of France (cf. Part I, Chapter 4). Similarly, this species of oak – found as the support of the Burgundian School Portrait of a Young Man in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Painting index, no. 173A) and the French Portrait of a Man with a Hawk in the Brooklyn Museum (Painting index, 133A) – orientates these panels toward a northern school. In another instance, the use of maritime pine confirms the attribution to the Spanish School of the same museum’s Jesus Among the Doctors (Painting index, no. 832A), and reaffirms the impossibility of the earlier attribution of this painting to Jean Malouel. Its attribution to the Catalan School would, however, constitute an anomaly. Lastly, the use of a spruce support for St Margaret and St Catherine at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Painting index, no. 360A) suggests that the panel is more likely to have originated in a southern German School (Swabia, Bavaria, Tyrol) than in France. »

60 Editors’ note: The complex and vast trade in timber between the 14th and the 17th century was not fully understood in the 1960s. As has been demonstrated by dendrochronological studies during the past four decades, the situation described by Marette should be significantly nuanced – although her main conclusion may serve as a first guideline. »