Description of the natural vegetation of the principal European regions1Use was made when preparing this chapter of data and documents made available to us by Professor P. Silvy-Leligois of the École Nationale des Eaux et Forêts in Nancy.

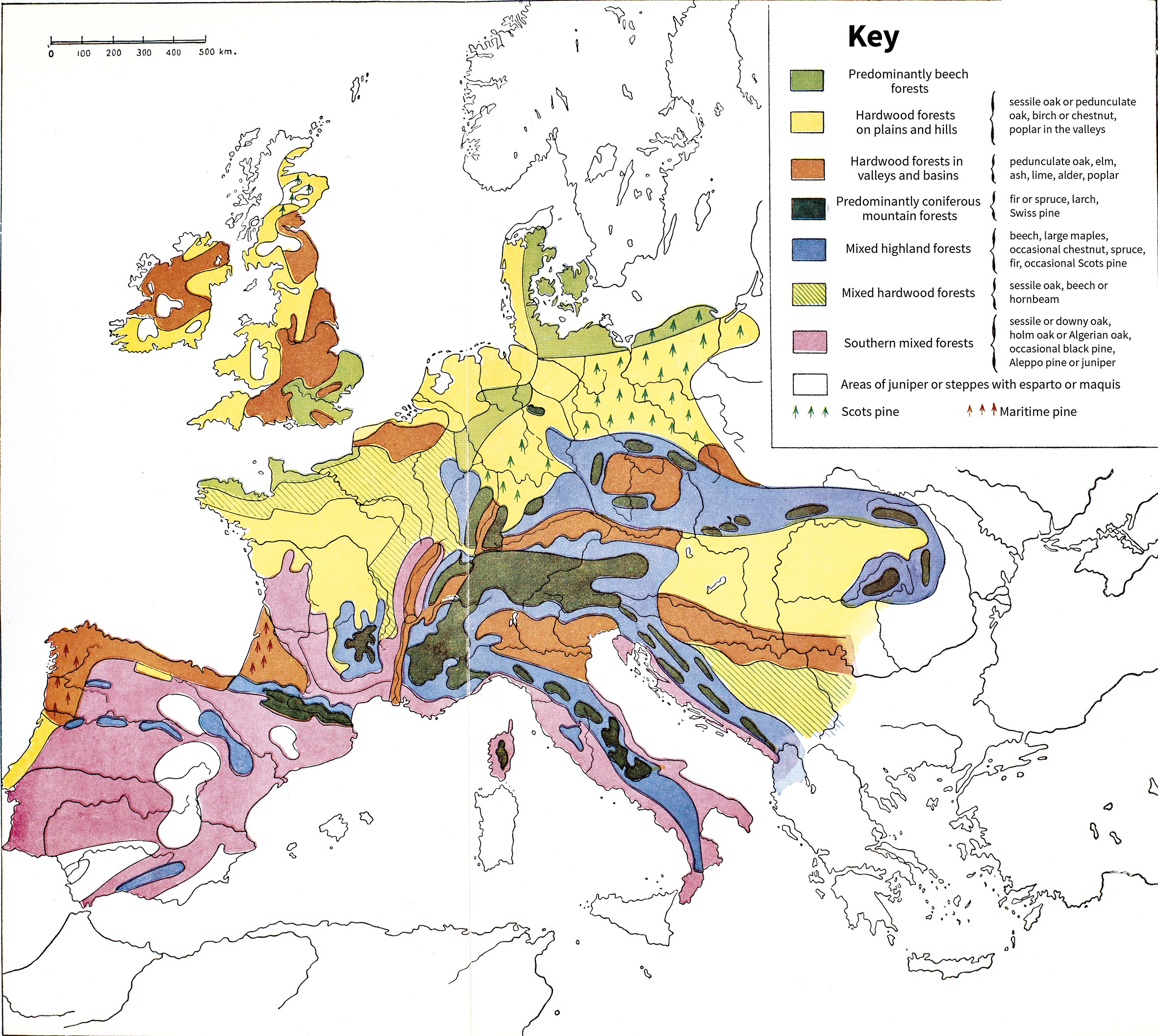

While current botanical groupings can be readily studied, knowledge of European forests in earlier periods is more difficult to obtain. Figure 38 shows a reconstruction of Europe’s forests from the 11th to the 16th century.2In addition to our study, we recommend reading the chapter ‘Variations sommaires du paysage forestier dans l’histoire’ in Blais 1947: 2–6. Editors’ note: See also Haneca et al. 2006: 137–44.

Figure 38 This European forest map is a sketch offering a breakdown of the overall natural vegetation of the main regions of Europe. It corresponds as precisely as possible with the forest vegetation in Europe before the 18th century. It makes no claims to mathematical rigour. In reality, there are no forest borders: the most that can be done is to identify forested zones. This ought to be borne in mind while consulting this document (see also Table 1).3Spain: pending evidence to the contrary, the spruce did not cross the natural cut-off formed by the Rhône valley. It is not found, therefore, in either the Massif Central or the Pyrenees. Beech has virtually disappeared from the mountains of the interior. Poplar: Poplars are found in certain northern valleys. The Netherlands: poplars are found in the valleys.

Land use and habitat were closely linked with the possibilities of cultivation. The most favourable regions were the large alluvial plains and basins. Since living conditions were harsh in highland areas and mountain ranges, settlements tended to be established at major river confluences and crossroads, to facilitate exchanges of every kind. We will attach particular importance to natural regions that combine these characteristics and where commercial, intellectual, and artistic activity has been concentrated since the Middle Ages. It would also be useful, however, to perform a secondary study of mountain areas which, while they have not been the sites of important human settlements, have nevertheless been places of transit, creating connections and exchanges between schools of art. We have in mind the Alpine passes that have been crossed through the ages, not only by soldiers, politicians and clergy, but also by artists. Movements of this kind may have contributed in a way that is worthy of analysis.

It was in the great plains and basins, however, that the major flows of traffic were concentrated, and it is to these natural regions that we can link the Flemish and Dutch schools, the central hubs of the Saône and Rhône valleys, the Loire basin, the various schools of the Po basin, and so on.

For the sake of clarity, we will individually examine the characteristics of the forest vegetation of the following regions:

•North European Plain

•high mountains

•hills and highlands

•Plains and basins

•Iberian Peninsula

North European Plain

This plain corresponds with areas subsided or eroded before the Tertiary period. Marine and glacial sediments, reworked to a greater or lesser extent by the great post-glacial rivers, mask the ancient terrain and give the landscape its characteristic appearance: Baltic ridges or hills, large sandy expanses, clay wetlands, chaotic uplands dotted with lakes and bogs, and remnants of the various moraines deposited by the northern glaciers. The regions west of the Elbe, which escaped the most recent glaciation, remained poorly drained lowlands.

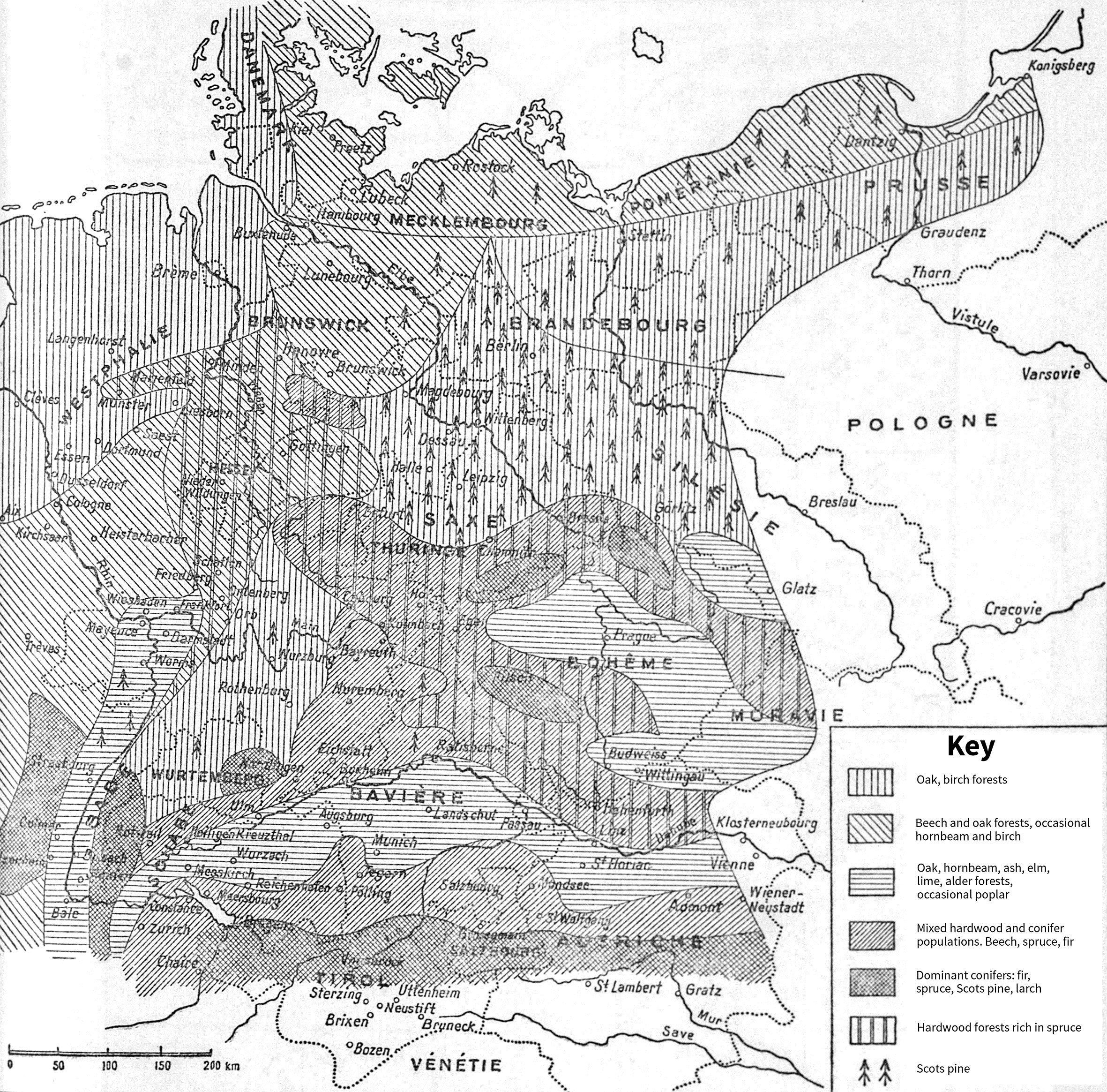

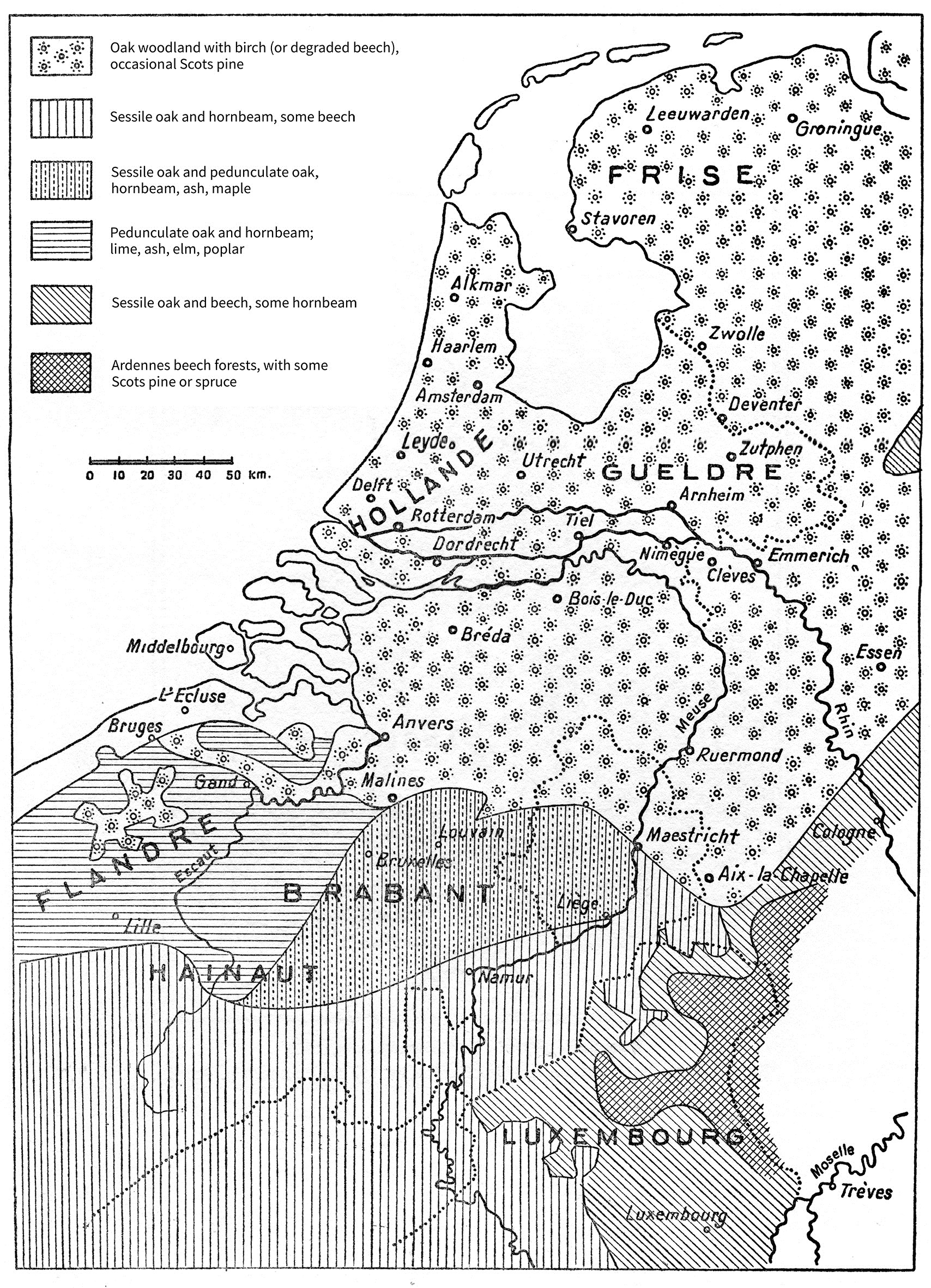

The colder period had a serious impact on forest vegetation, no doubt eliminating the majority of the primitive species. Vegetation re-established itself by means of more northern species, which were better adapted to the new soil conditions. Within their apparent uniformity, the diversity of the populations reflects the variation in the soil and climatic influences. Moving from north to south and west to east, an increase is noted in continental influences and in the porosity of the soil, in which the proportion of fine elements declines. As a result, the hardwood varieties that are still abundant in coastal areas diminished and the proportion of conifers increased. Beech, for instance, that is abundant in Jutland and northwest Germany, and can still be found mixed in with Scots pine on the Baltic coast, disappeared east of the Vistula river.

Mixed hardwood populations – sometimes comprising pedunculate oak, elm, lime, birch, alder and aspen, sometimes sessile oak, beech, and hornbeam or sessile oak and birch – started to include an increasing proportion of Scots pine. Hardwood forests, rich in pedunculate oak, lime, ash, and hornbeam, would later reappear in Silesia and the Central Polish Lowlands.

High mountains

This zone comprises the sub-Alpine and Alpine levels of the Alps, Pyrenees, Carpathians and Balkans ranges. The almost total disappearance of hardwood species contrasts with the abundance of conifers. The mountains of central and eastern Europe then as now are dominated by spruce and larch, mingled in some cases with Swiss pine and mountain pine. These woods display certain specific qualities due to the fineness and regularity of their growth rings. Spruce is used in violin making and Swiss pine for sculpture. The equivalent levels in the Massif Central and Pyrenees, where spruce does not occur, are rich in fir (Pinus uncinata) and Scots pine.

Hills and highlands

This level, corresponding with heavily eroded, ancient mountains, the lower slopes of mountain ranges, and the low reliefs surrounding the basins, is frequently found in central and western Europe. It is characterised by a rich mix of hardwood and conifer species, favoured by a high moisture content or abundant precipitation and by generally favourable soil conditions: young or rejuvenated siliceous clay or calcareous clay soils.

These formations mark the transition between the hardwood forests of the plains, in which oaks predominate, and the coniferous forests of the mountains. Beech and fir are particularly important in this intermediate zone. Local conditions may, however, favour certain varieties – spruce in one case, Scots pine in another; elsewhere fir or beech – thus disguising the transitional character. Conifers are therefore significant in the Harz, Fichtel, Swabian, and Franconia ranges, the Bavarian highlands, the Bohemian quadrilateral, and the Black Forest, whereas they only appear as commensals in the mixed hardwood forests of Thuringia, Silesia, Moravia, etc.

These mixed forests, which are very characteristic of the Hercynian zone and central Europe, become progressively simpler as one moves west and south. Spruce is confined in this case to the higher mountains. The constituent species, beech and fir, remain dominant, with oak, maple and elm as secondary varieties. Scots pine remains localised in the northeast, on the warm, rocky sandstone slopes of the Vosges, for instance; in the southeast, it forms fairly continuous forestation above the downy oak, where it occasionally replaces beech.

The same level of highlands is found around the periphery of the Massif Central and the slopes of the Pyrenees, but with a marked increase in the prevalence of fir. Lastly, we can also include in this category, the plateaux and hills of northeastern France, where beech takes a lead over other hardwood varieties.

Plains and basins

We have already stressed the importance of this zone in terms of human settlement. The natural conditions here are particularly favourable. Tertiary and quaternary formations predominate, superimposed on occasion by calcareous strata dating from the Jurassic or Cretaceous.

The pronounced openness of these plains to western influences moderates the climate and ensures fairly regular precipitation. Mixed hardwood forests are typical of this entire zone, largely dominated by oak: sessile oak associated with beech, fruit trees or hornbeam in the east, and on the periphery of the Paris Basin; more localised pedunculate oak in the alluvial valleys or low-lying plains, with an abundant tail of lime, elm, ash, alder and, occasionally, poplar. In some basins, with predominantly siliceous soils, oak is mixed with birch, and in the southwest with maritime pine. The zone was enriched – probably from around the Roman period – by Mediterranean-Asian contributions, of which we are interested in the chestnut and walnut tree.

The chestnut was introduced to the siliceous areas4Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 209. on the periphery of the Massif Central and beyond the threshold of the Poitou region as far as the Paris Basin. This species also spread northeast via the Rhône valley. The chestnut is likely to have appeared in the northern half of France by the 15th century.5In the iconography of the trades of that era, Gathering Chestnuts dates from the 15th century (Fig. 65).

The walnut occurs naturally in Iran.6Schmucker 1942: map 122. ‘Imported from Persia to Italy around the beginning of the Christian era, it was introduced into France, and later into England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth [I].’7Macquoid 1904–1908, II: 5. Walnut is a non-forest species and was used in France to plant orchards.8A 15th-century Beating a Walnut Tree is particularly significant (Fig. 67). According to A. Wollbrett, ‘after the Revolution, citizenship rights were accorded on the territory of the Abbey of Saint-Jean-les-Saverne, on approval by the Lady Abbess ... and payment of a fee ... which was accompanied by the planting of two young walnut tree’.9Wollbrett: 1957: 20, 21. Walnut was introduced to the Dauphiné, Périgord, Dordogne, Limousin and Quercy regions of France, where it was dispersed around alluvial terraces with deep, rich soil. It is fairly abundant in the valleys of the Garonne, Burgundy and Normandy, and also in the valleys of the Loire basin. It gradually becomes scarcer in Champagne and Lorraine, but then encounters favourable conditions once more in more easterly regions, where it enjoys a warmer and sunnier localised climate: in Alsace, for instance, and the Swiss Plateau, and then as far as the Upper Rhine valley.

In the same vein, the importance should be noted of poplar plantations in all the alluvial valleys: in the Netherlands, in France – in the northeast (Aube, Seine, Marne), west and southwest (Bocage, Loire, Brittany, Garonne, etc.) – in the plains of the Rhône and the Po, and in certain valleys of northern Spain. Poplar wood has always been used for a variety of purposes through the ages, from furniture to construction. Despite its low tensile strength, poplar was attractive as lumber in a period before the widespread use of softwood.

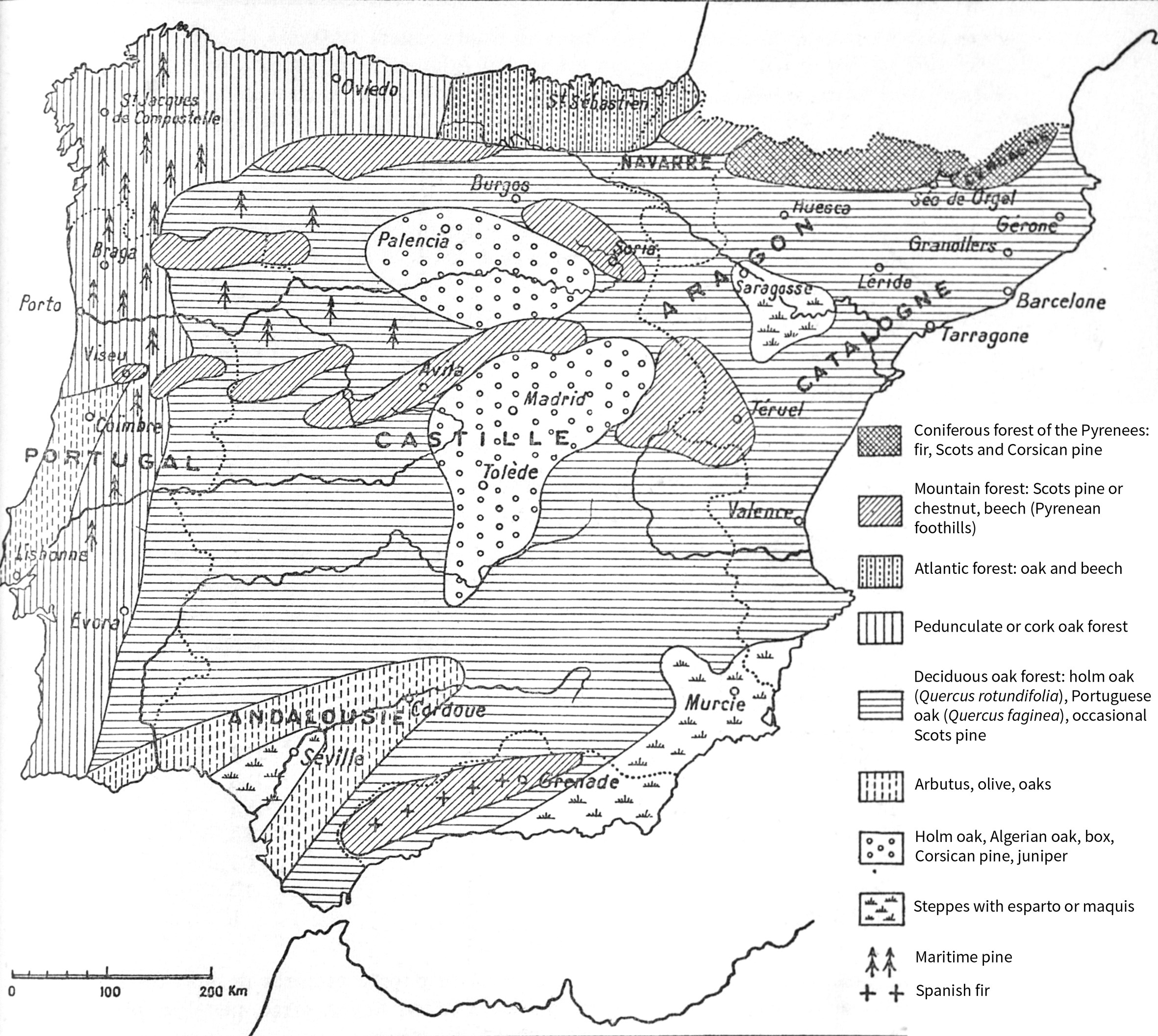

Iberian Peninsula

The picture presented by the various natural regions of Spain is similar to the European average. However, the destruction of its forest vegetation makes any precise description difficult. Judging by the residual forestation, it is however possible to detect the importance of oaks in the plains and highlands, Scots pine in all the mountain ranges, poplar in the valleys, and maritime pine along the entire Atlantic coast. Beech no longer occurs on a significant scale, except in the foothills of the Pyrenees and in certain small valleys, where it has been protected from destruction. Fir, which is abundant on the French side of the Pyrenees, grows less frequently on the Spanish side, although without disappearing entirely. Spanish fir is found in southern Spain, in the Sierra Nevada. Spruce does not occur anywhere in the Iberian Peninsula.

Finally, according to Gonzalez Vasquez, the climate and site conditions in Galicia, Catalonia, Aragon and Andalusia are favourable to walnut, which is currently present and which may be assumed to have been so in the past.10Gonzalez Vasquez 1947: 346. Théodore Schmucker11Schmucker 1942: map 50. locates the thuja in the south of the Iberian Peninsula and in North Africa, while P. Boudy12Boudy 1950, II: 706, 707. places it more specifically in the Cartagena region.

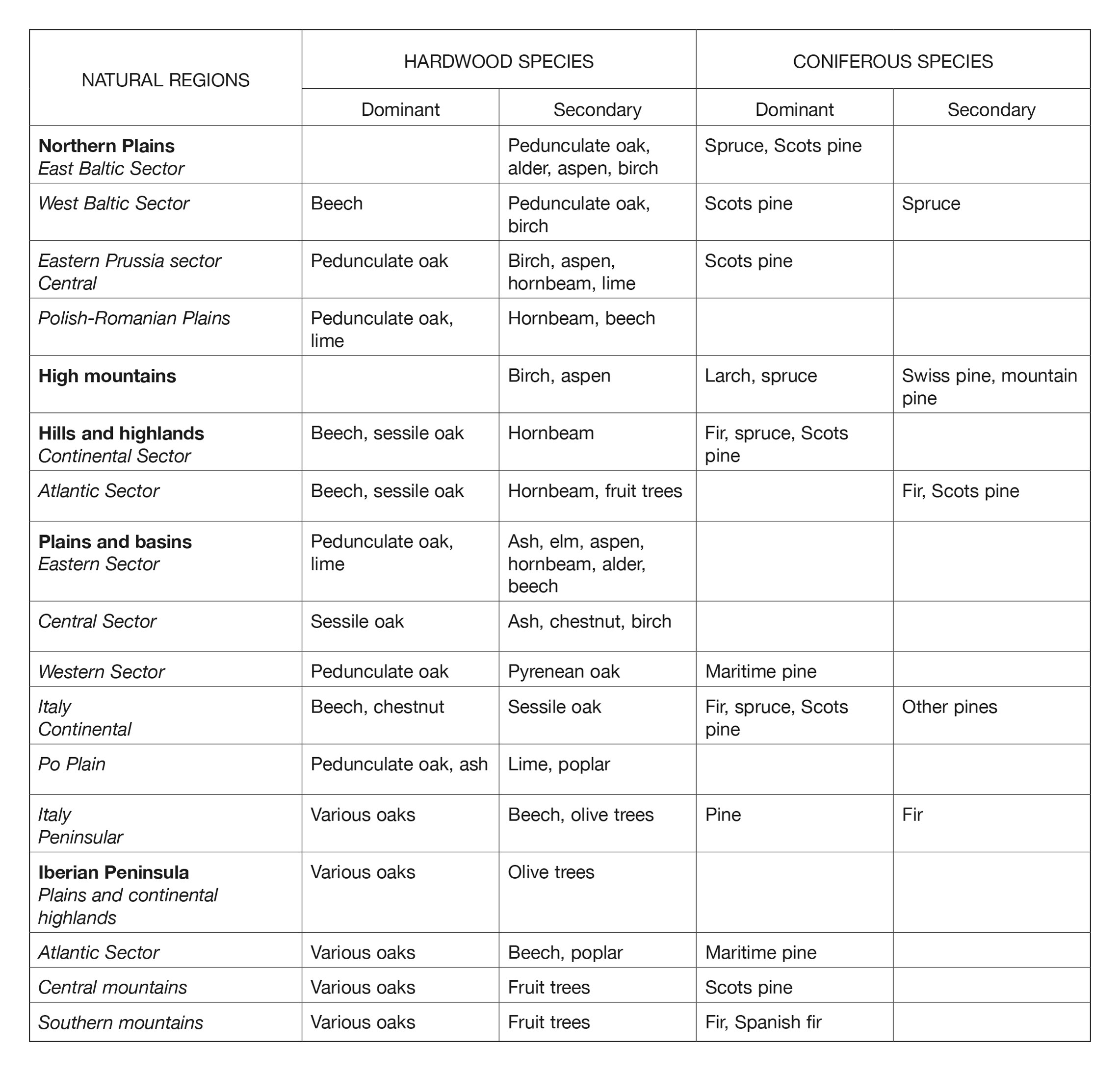

Table 1 contains a list of the varieties typical of the different forest regions described above.

Table 1 Distribution of forests in Europe prior to the 18th century.

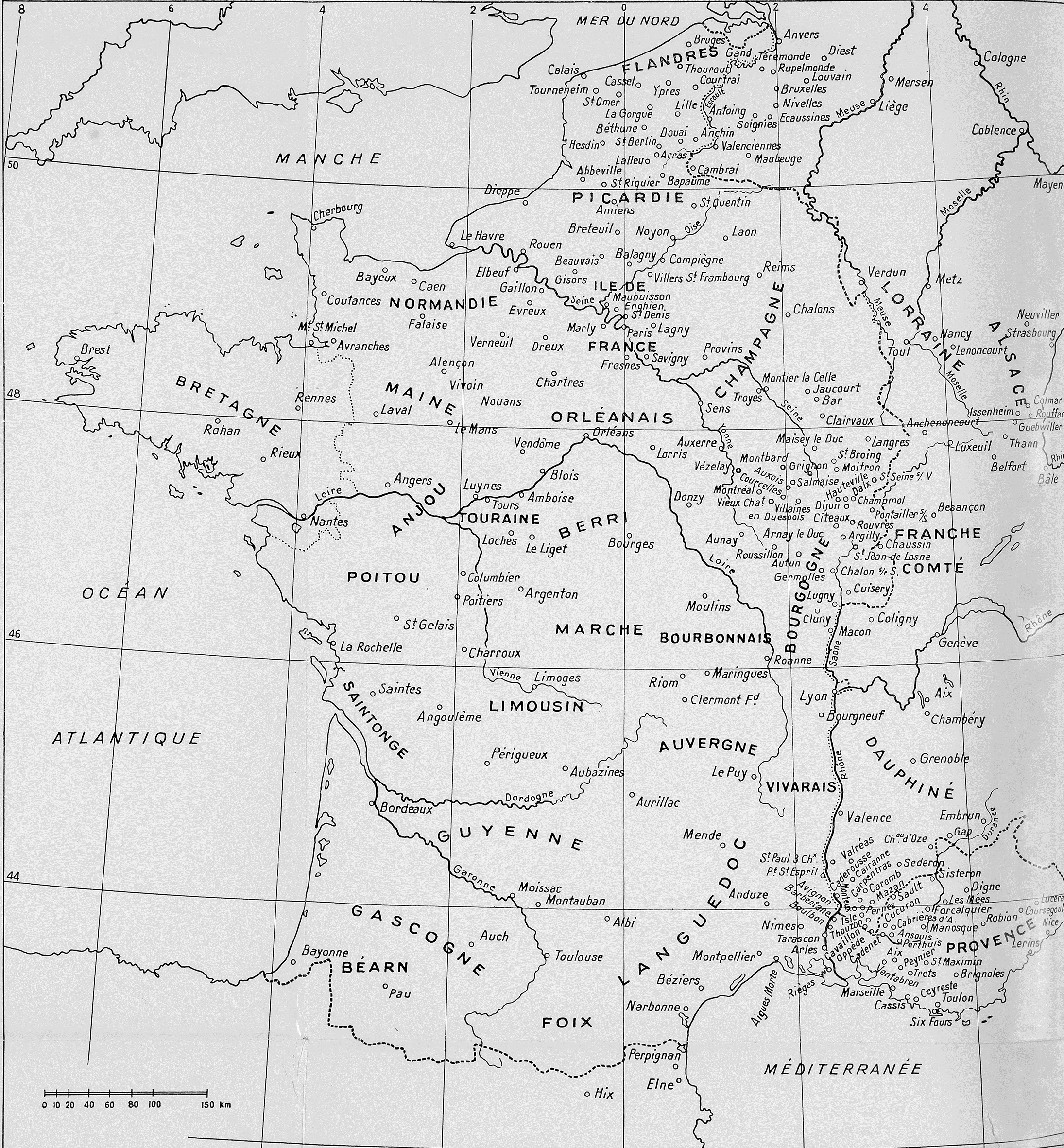

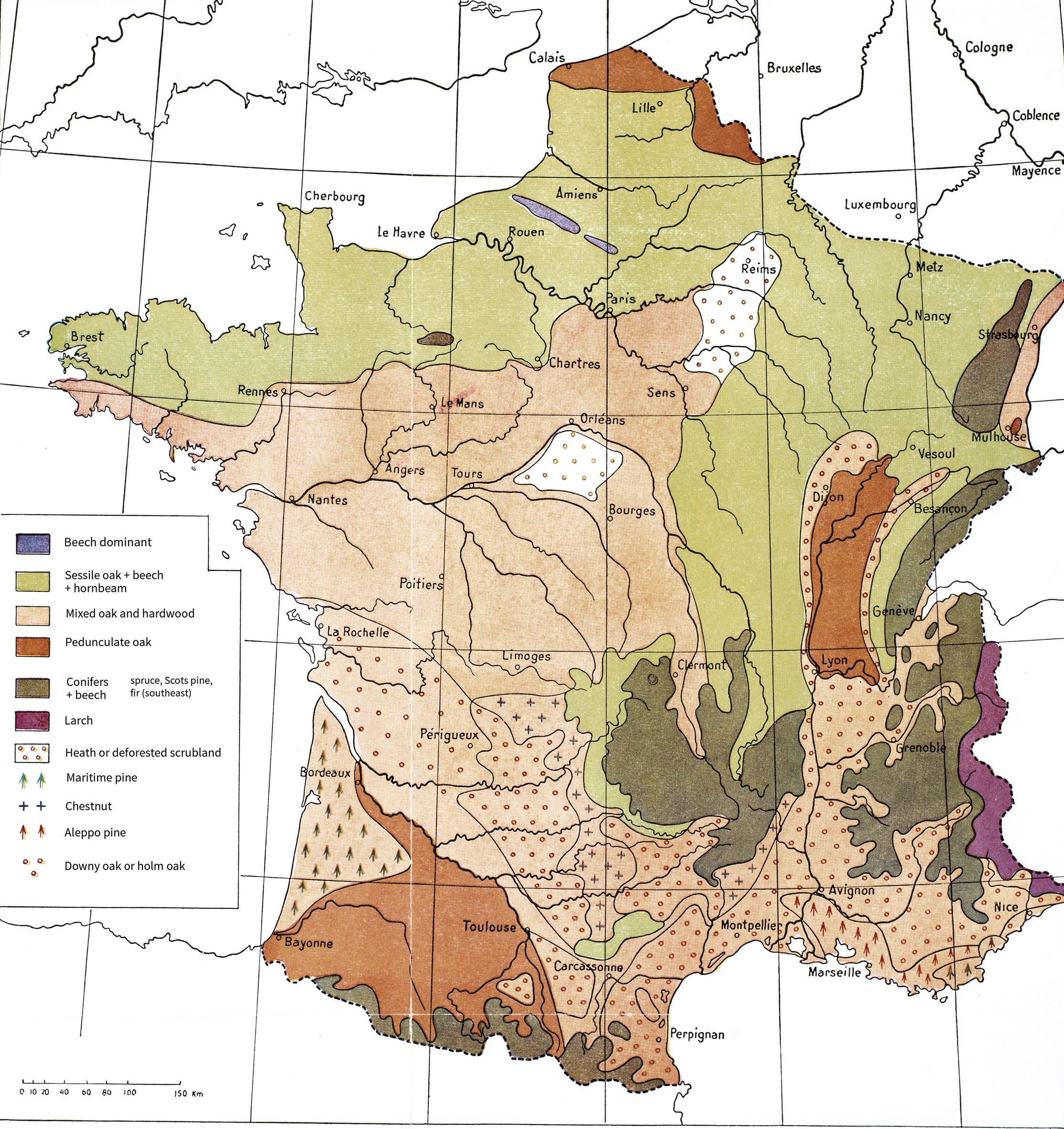

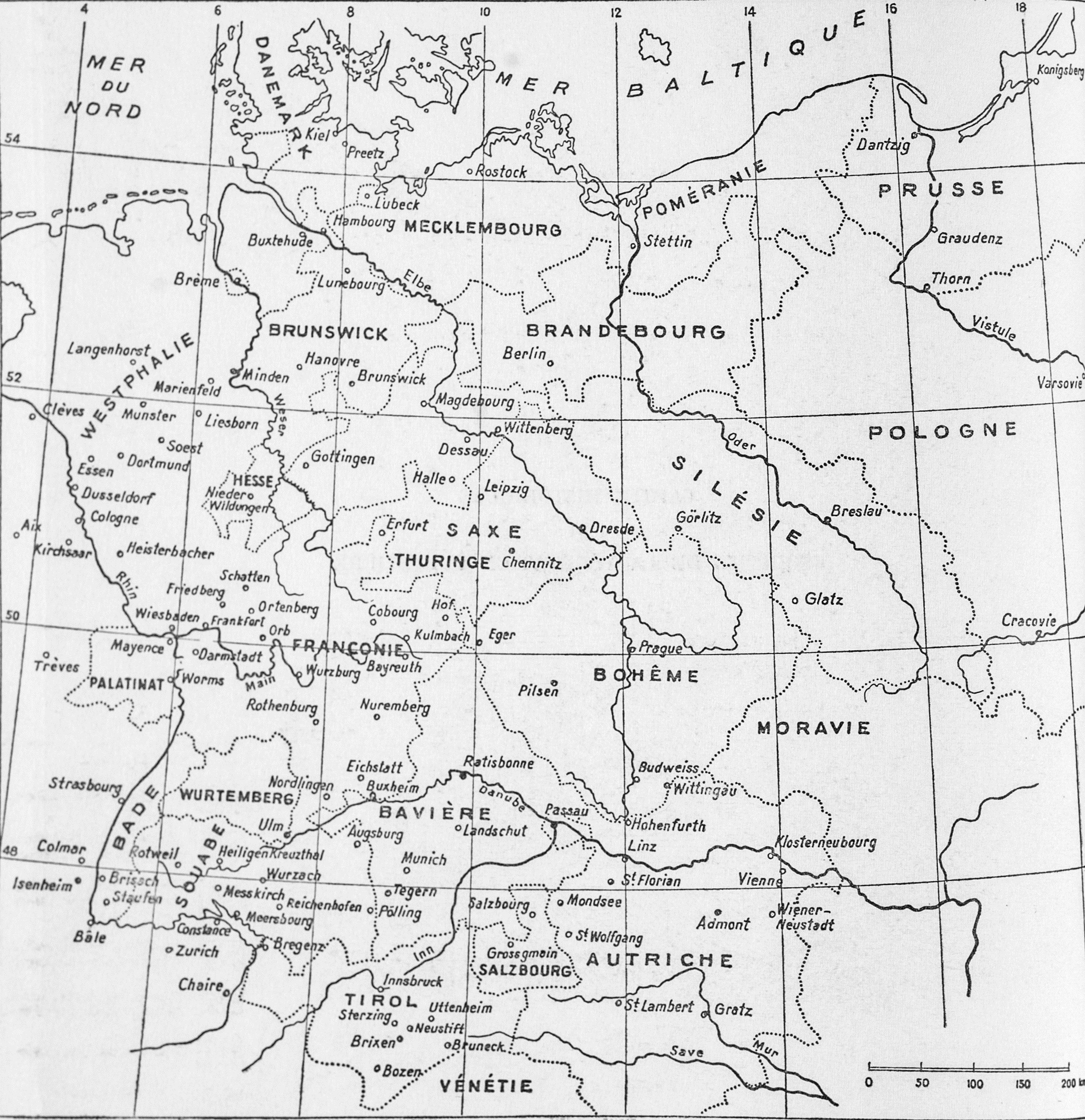

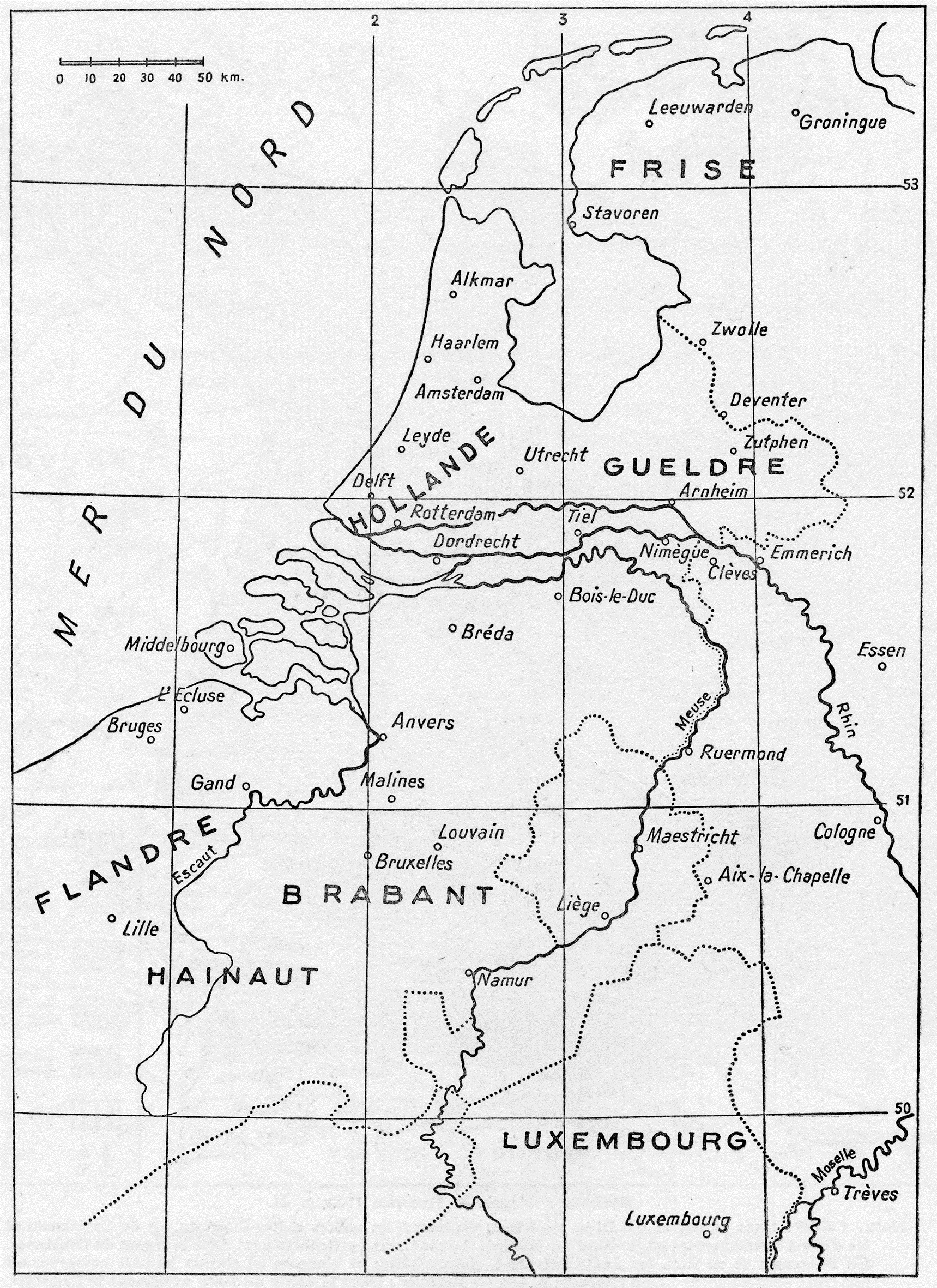

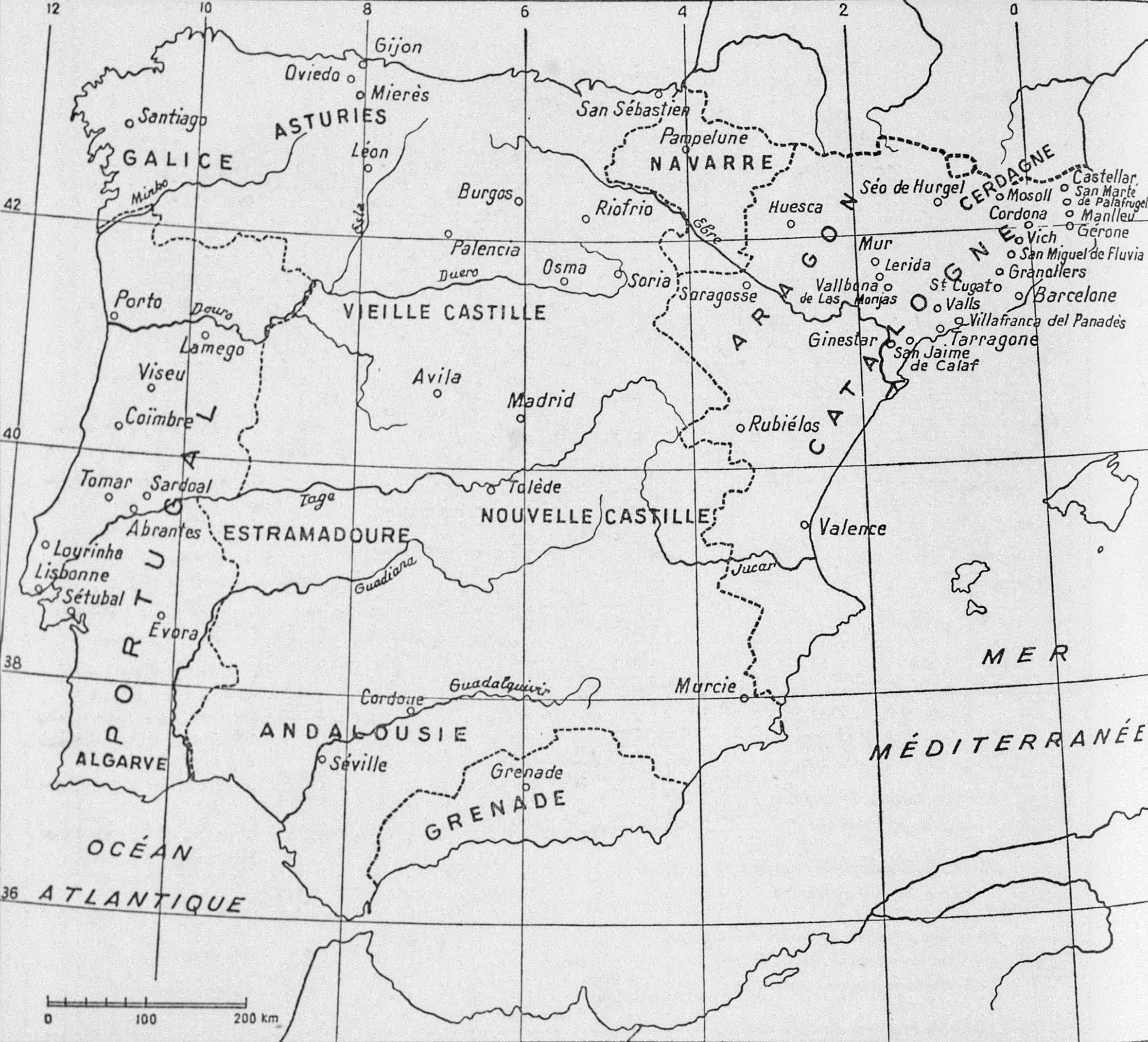

Sketches of the natural vegetation and medieval geographical maps of the regions studied13These sketches were prepared based on information provided by Prof. P. Silvy-Leligois of the École Nationale des Eaux et Forêts in Nancy, and the following works: Europe: Westermann 1956: 92–3; Vidal de La Blache and Gallois 1927–1934, IV: 86; Rubner and Reinhold 1953; P. Silvy-Leligois, personal communication; France: Gaussen 1942–1945: pl. 26, 30, 31, 32, 33; Rol 1935: pl. 38; Iberian Peninsula: Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 211; Vidal de La Blache and Gallois 1927–1934, VII: 85; Ceballos and Córdoba 1942: 1; Gonzalez Vasquez 1947: 346, 360 ; Boudy 1950: 706, 707 ; Schmucker 1942 : map 40 ; Italy: Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 227; The Netherlands and Belgium: Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 118; Germany: Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 44; Great Britain: Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 114. The historical maps were prepared by the author, drawing on the following works, exhibition catalogues and art publications: Schrader 1896; Westermann 1956: 92, 93; Vidal de La Blache 1950: 29, 31; Dictionnaire des postes de l’Empire 1859; Cottineau 1935–1937; Laclotte 1956: 1; Exposition des Maîtres de Cologne à Albert Dürer, Paris 1950, p. 18; Ring 1949: 255 ff; Sterling 1955: ix.

Forest sketches

The following forest maps (Figs 39–50) are sketches offering a breakdown of the overall forest vegetation prior to the 18th century. They make no claims to mathematical rigour. In reality, there are no forest borders: the most that can be done is to identify forested zones. This ought to be borne in mind while consulting these documents.

Walnut, which is a non-forest species, is not included in the map keys. It is found scattered around temperate regions, in plains and agricultural basins, and its location is indicated in a brief text following each map.

Figure 39 Historical map of medieval France.14The names indicated in this map were mostly taken from the historical texts cited in the course of this book. The author located places that no longer exist or are little known today based on the Dictionnaire des Postes de l’Empire 1859 and Cottineau 1935–1937; also Vidal de La Blache 1950: 28–9; Sterling 1955: ix; Ring 1949: 255ff.

Figure 40 Sketch of forest vegetation in France prior to the 18th century.15We consider this map to reflect the medieval situation. While some might consider this a step too far, the diagram nonetheless shows the distribution of the major forest types in relation to the climate. Since the latter has not changed significantly in the preceding centuries, it may be concluded that it represents the physiognomy of French forests in the Middle Ages with sufficient precision. All that would be required to bring it up to date would be to add the types of forest introduced artificially, primarily since the early 19th century: the pine forests of the Champagne and Sologne regions. Fir, spruce, larch: conifers such as fir, spruce, and larch, which occur naturally in the mountains, have also featured in the reforestation of numerous regions. Spruce is not found in the Lyonnais region, in the Pyrenees or in the Massif Central. It does occur in the Ain region, in the vicinity of the Jura, and in Burgundy. Fir is essentially localised in the region between Draguignan and the Italian border. Scots pine is found in the Lyonnais Mountains. Poplar: the broad alluvial valleys have been frequently planted with hybrid poplars in the past three-quarters of a century, radically altering the landscape, because of the often large areas involved. The ‘wild poplar’ of the Garonne and Rhône valleys, which was used in the Middle Ages, tended to come instead from ‘forest galleries’ running along the rivers (information kindly provided by R. Blais, Director of the Institut Agronomique de Paris, and published here with his kind authorisation). Elm, willow, lime and ash are found in the same regions. Walnut, which is a non-forest species, was planted diffusely to the south of the Loire, in the Périgord, Dordogne, Limousin, and Quercy regions. It was fairly abundant in the valleys of the Garonne, in Burgundy and in Normandy. Oak, which was widespread in the Rhône valley in the Middle Ages, has almost disappeared in our own time. Chestnut is found – outside the indicated zones – beyond the threshold of the Poitou region as far as the Paris Basin.

Figure 41 Historical map of Germany in the 15th–16th century.

Figure 42 Sketch of forest vegetation in France prior to the 18th century.16Lime: there is a distinction in the Upper Rhine region between the rich valleys (around Lake Constance) and the mountainous regions, where lime has been eradicated. It is especially prevalent in the Constance region. Mixed oak, beech and hornbeam forests at moist locations in Franconia and Saxony include a high proportion of lime (Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 86). Poplar: there are riparian forests rich in poplar and willow in the Rhine valley adjoining the Palatinate, and in the Bavarian Basin (Rubner and Reinhold 1953). Fir is found in mixed forests and hardwood forests rich in spruce, but only in small quantities. Walnut is encountered in favourable conditions in regions with the warmest and sunniest climate, such as Alsace, the Swiss Plateau and the Upper Rhine valley, where it has been extended by cultivation, but in a more recent period.

Figure 43 Historical map of the Low Countries in 1494.

Figure 44 Sketch of forest vegetation in the Low Countries prior to the 18th century.17Poplar is found in the valleys of the Netherlands.

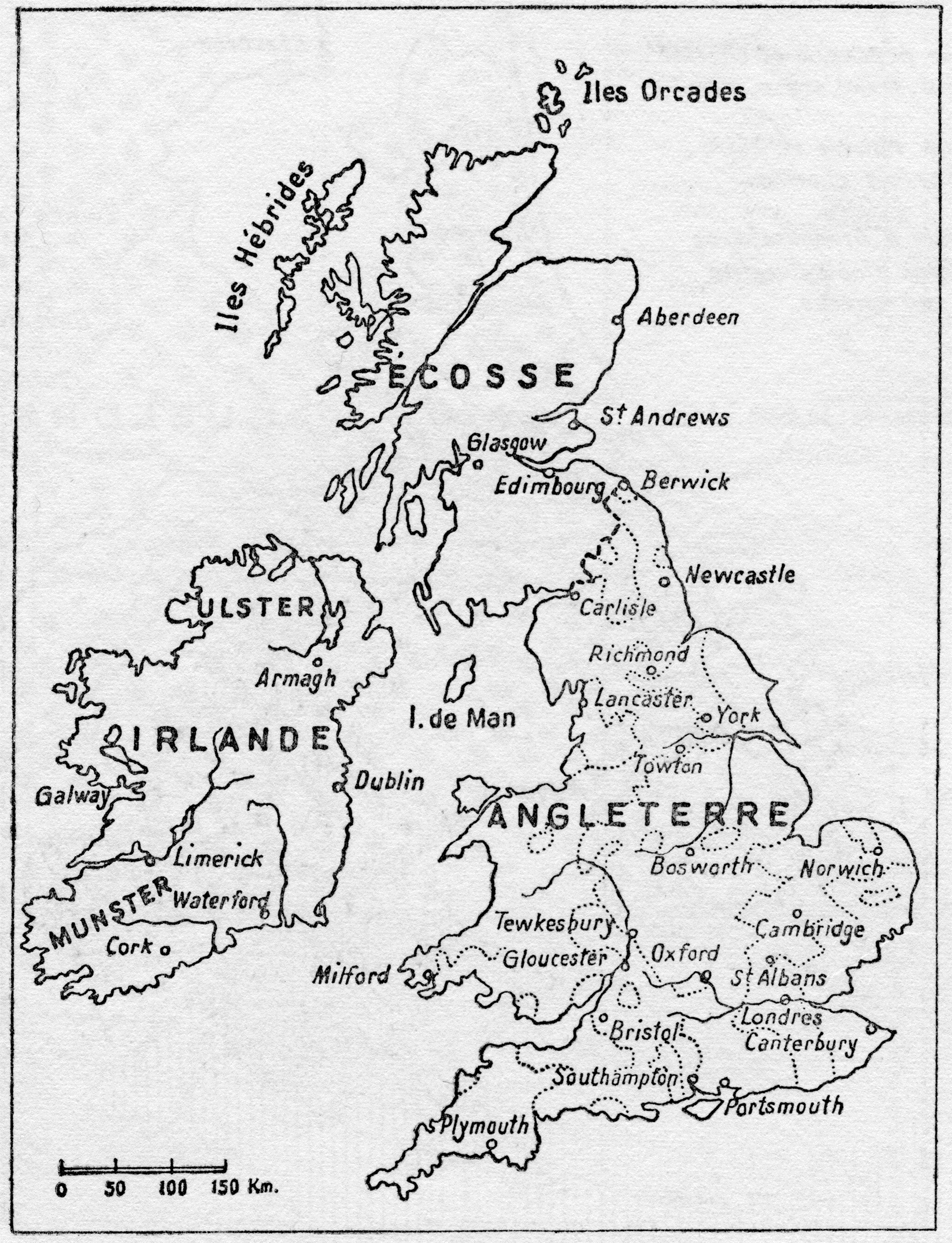

Figure 45 Historical map of the British Isles in 1476.

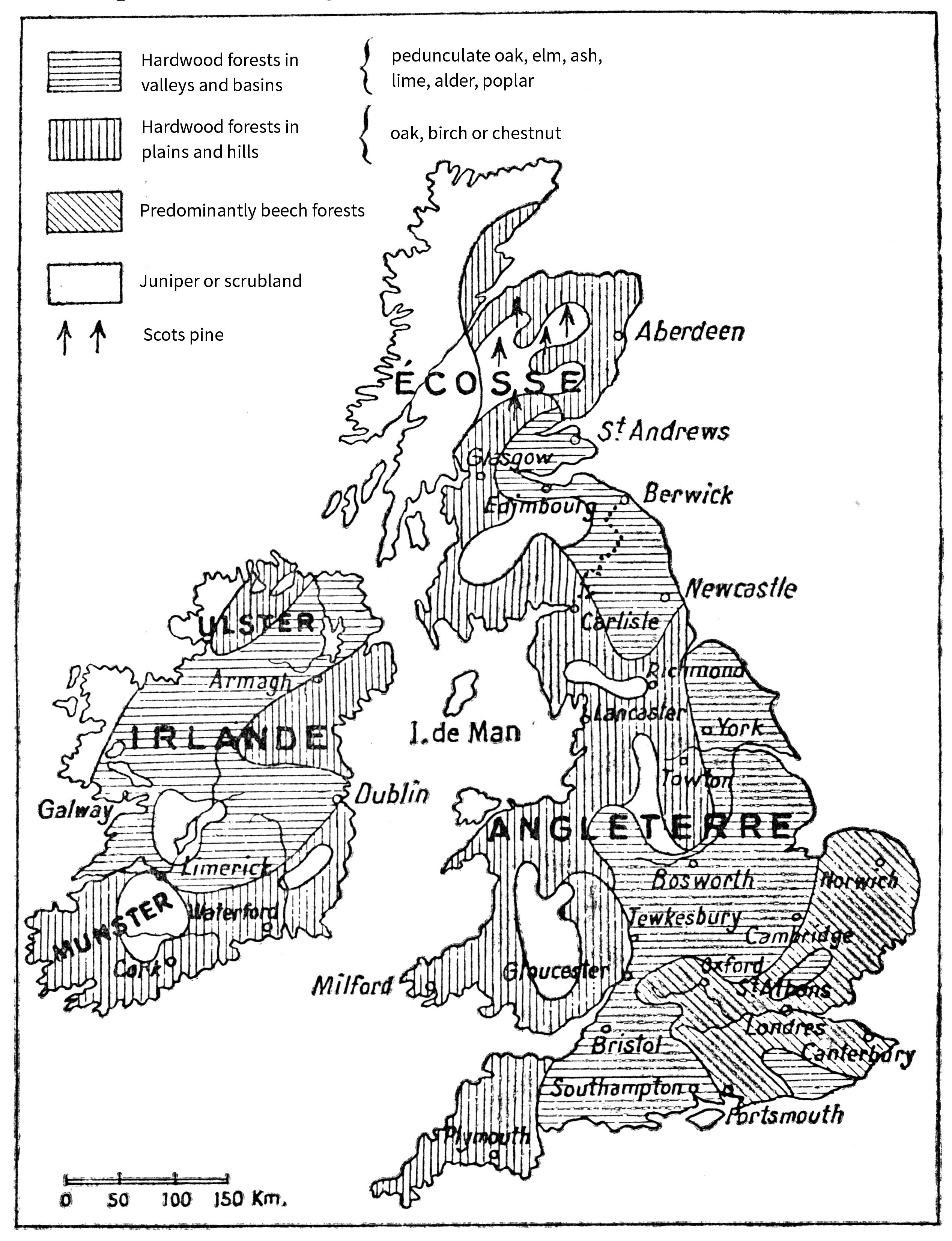

Figure 46 Sketch of forest vegetation in the British Isles prior to the 18th century.18Walnut was introduced to Britain during the Roman occupation. It was not used in woodworking before the 17th century (Macquoid 1904–1908, 2: 5–6). Elm and yew are naturally occurring varieties.

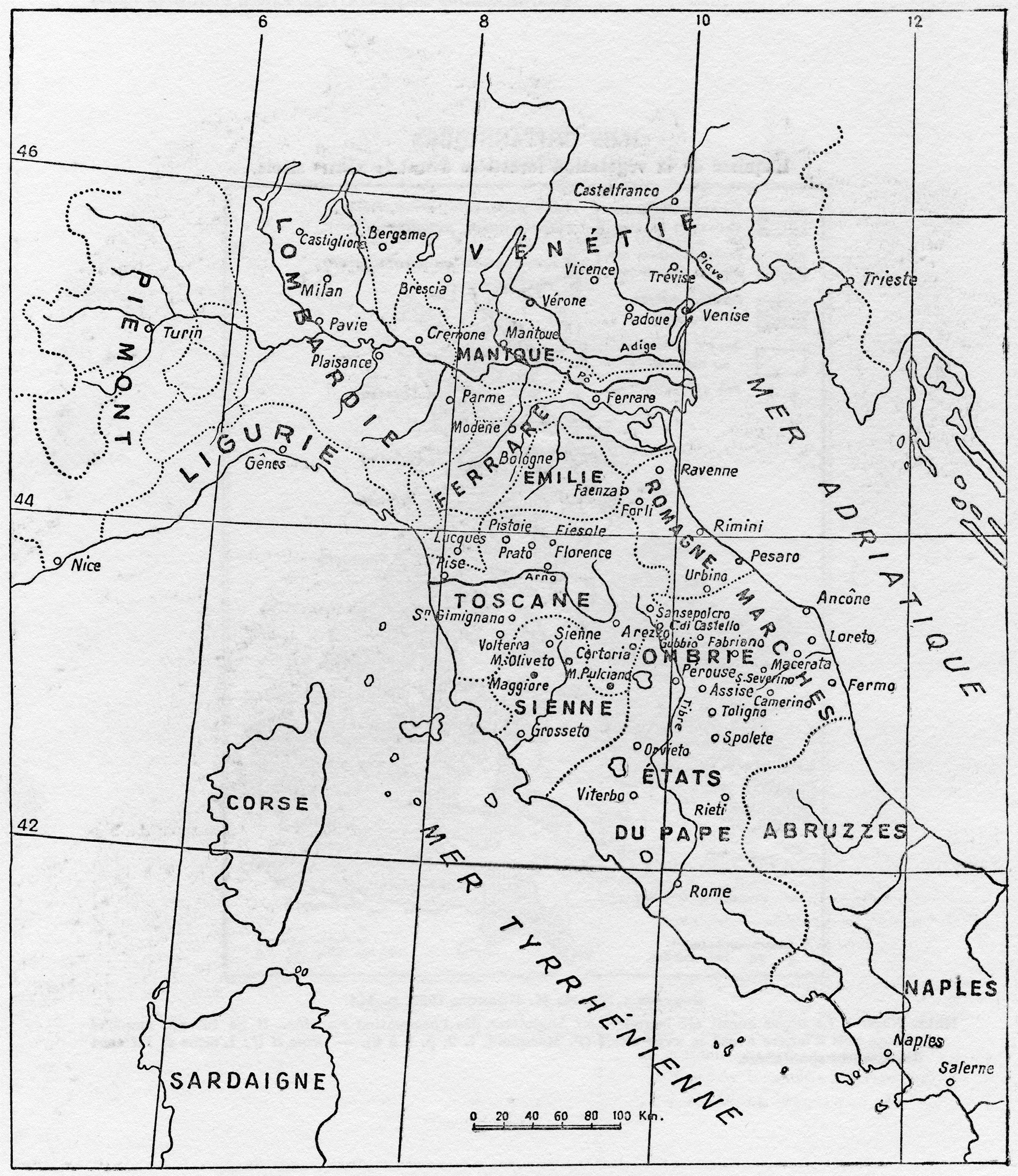

Figure 47 Historical map of Italy in the 14th–15th century.

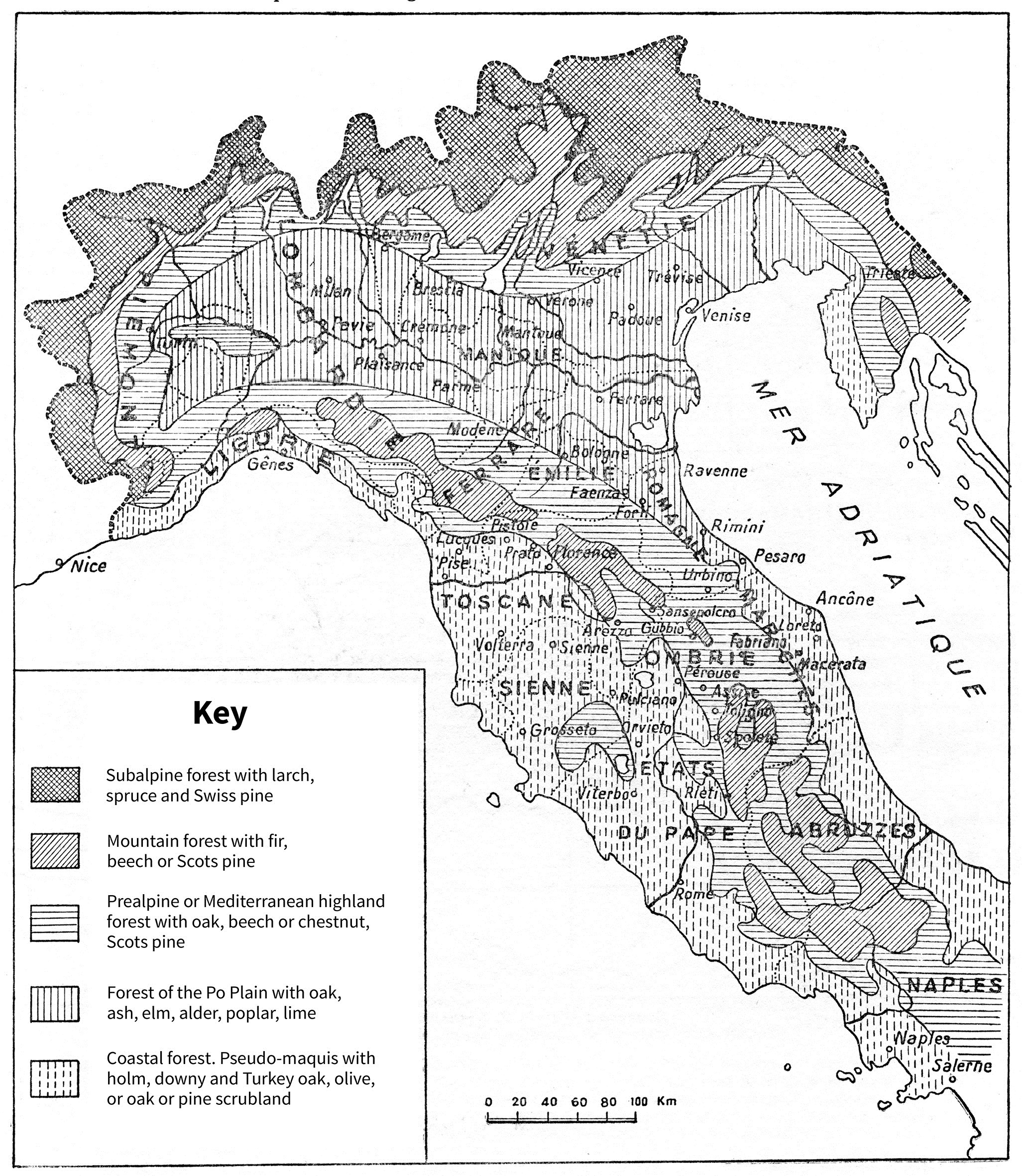

Figure 48 Sketch of forest vegetation in Italy prior to the 18th century.19Poplar is found in all the valleys of the Italian peninsula. As in France, willow occurs with poplar in the valleys. Walnut is dispersed throughout the territory, with its warm, sunny climate.

Figure 49 Historical map of Spain and Portugal in 1494.

Figure 50 Sketch of forest vegetation in Spain and Portugal prior to the 18th century.20Maritime pine occurs north of San Sebastian, in the Bay of Biscay area. The climate and site conditions in Galicia, Catalonia, Aragon and Andalusia are favourable to the walnut, which is currently present and may be assumed to have been so in the past (Gonzalez Vasquez 1947: 360). The black and white poplar (i.e. the indigenous species) occurs in the valleys of northern Spain, especially Catalonia (Gonzalez Vasquez 1947: p. 346). Chestnut is found in the indicated areas, which correspond with the mountain forests, but only in areas with siliceous soil (Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 209). Beech: the Arab invasion from the 8th to the 13th century profoundly altered the ancient physiognomy of the flora. First and foremost, the deforestation of large areas of Spain made the country more arid. Beech disappeared in many cases, to be replaced by Scots pine and, like fir, only survives in the mountains. It no longer occurs on a significant scale, except in the foothills of the Pyrenees and in certain small valleys, where it has been protected from destruction. Scots pine: sporadic species located below the zone of fir on the eastern foothills of the Spanish Pyrenees (Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 211). Thuja: Schmucker (1942) locates this species in the south of the Iberian Peninsula and in North Africa. Boudy (1950: 706, 707) places it more specifically in the Cartagena region.

1 Use was made when preparing this chapter of data and documents made available to us by Professor P. Silvy-Leligois of the École Nationale des Eaux et Forêts in Nancy. »

2 In addition to our study, we recommend reading the chapter ‘Variations sommaires du paysage forestier dans l’histoire’ in Blais 1947: 2–6. Editors’ note: See also Haneca et al. 2006: 137–44. »

3 Spain: pending evidence to the contrary, the spruce did not cross the natural cut-off formed by the Rhône valley. It is not found, therefore, in either the Massif Central or the Pyrenees. Beech has virtually disappeared from the mountains of the interior. Poplar: Poplars are found in certain northern valleys. The Netherlands: poplars are found in the valleys. »

4 Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 209. »

5 In the iconography of the trades of that era, Gathering Chestnuts dates from the 15th century (Fig. 65). »

6 Schmucker 1942: map 122. »

7 Macquoid 1904–1908, II: 5. »

9 Wollbrett: 1957: 20, 21. »

10 Gonzalez Vasquez 1947: 346. »

11 Schmucker 1942: map 50. »

12 Boudy 1950, II: 706, 707. »

13 These sketches were prepared based on information provided by Prof. P. Silvy-Leligois of the École Nationale des Eaux et Forêts in Nancy, and the following works: Europe: Westermann 1956: 92–3; Vidal de La Blache and Gallois 1927–1934, IV: 86; Rubner and Reinhold 1953; P. Silvy-Leligois, personal communication; France: Gaussen 1942–1945: pl. 26, 30, 31, 32, 33; Rol 1935: pl. 38; Iberian Peninsula: Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 211; Vidal de La Blache and Gallois 1927–1934, VII: 85; Ceballos and Córdoba 1942: 1; Gonzalez Vasquez 1947: 346, 360 ; Boudy 1950: 706, 707 ; Schmucker 1942 : map 40 ; Italy: Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 227; The Netherlands and Belgium: Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 118; Germany: Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 44; Great Britain: Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 114. The historical maps were prepared by the author, drawing on the following works, exhibition catalogues and art publications: Schrader 1896; Westermann 1956: 92, 93; Vidal de La Blache 1950: 29, 31; Dictionnaire des postes de l’Empire 1859; Cottineau 1935–1937; Laclotte 1956: 1; Exposition des Maîtres de Cologne à Albert Dürer, Paris 1950, p. 18; Ring 1949: 255 ff; Sterling 1955: ix. »

14 The names indicated in this map were mostly taken from the historical texts cited in the course of this book. The author located places that no longer exist or are little known today based on the Dictionnaire des Postes de l’Empire 1859 and Cottineau 1935–1937; also Vidal de La Blache 1950: 28–9; Sterling 1955: ix; Ring 1949: 255ff. »

15 We consider this map to reflect the medieval situation. While some might consider this a step too far, the diagram nonetheless shows the distribution of the major forest types in relation to the climate. Since the latter has not changed significantly in the preceding centuries, it may be concluded that it represents the physiognomy of French forests in the Middle Ages with sufficient precision. All that would be required to bring it up to date would be to add the types of forest introduced artificially, primarily since the early 19th century: the pine forests of the Champagne and Sologne regions. Fir, spruce, larch: conifers such as fir, spruce, and larch, which occur naturally in the mountains, have also featured in the reforestation of numerous regions. Spruce is not found in the Lyonnais region, in the Pyrenees or in the Massif Central. It does occur in the Ain region, in the vicinity of the Jura, and in Burgundy. Fir is essentially localised in the region between Draguignan and the Italian border. Scots pine is found in the Lyonnais Mountains. Poplar: the broad alluvial valleys have been frequently planted with hybrid poplars in the past three-quarters of a century, radically altering the landscape, because of the often large areas involved. The ‘wild poplar’ of the Garonne and Rhône valleys, which was used in the Middle Ages, tended to come instead from ‘forest galleries’ running along the rivers (information kindly provided by R. Blais, Director of the Institut Agronomique de Paris, and published here with his kind authorisation). Elm, willow, lime and ash are found in the same regions. Walnut, which is a non-forest species, was planted diffusely to the south of the Loire, in the Périgord, Dordogne, Limousin, and Quercy regions. It was fairly abundant in the valleys of the Garonne, in Burgundy and in Normandy. Oak, which was widespread in the Rhône valley in the Middle Ages, has almost disappeared in our own time. Chestnut is found – outside the indicated zones – beyond the threshold of the Poitou region as far as the Paris Basin. »

16 Lime: there is a distinction in the Upper Rhine region between the rich valleys (around Lake Constance) and the mountainous regions, where lime has been eradicated. It is especially prevalent in the Constance region. Mixed oak, beech and hornbeam forests at moist locations in Franconia and Saxony include a high proportion of lime (Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 86). Poplar: there are riparian forests rich in poplar and willow in the Rhine valley adjoining the Palatinate, and in the Bavarian Basin (Rubner and Reinhold 1953). Fir is found in mixed forests and hardwood forests rich in spruce, but only in small quantities. Walnut is encountered in favourable conditions in regions with the warmest and sunniest climate, such as Alsace, the Swiss Plateau and the Upper Rhine valley, where it has been extended by cultivation, but in a more recent period. »

18 Walnut was introduced to Britain during the Roman occupation. It was not used in woodworking before the 17th century (Macquoid 1904–1908, 2: 5–6). Elm and yew are naturally occurring varieties. »

19 Poplar is found in all the valleys of the Italian peninsula. As in France, willow occurs with poplar in the valleys. Walnut is dispersed throughout the territory, with its warm, sunny climate. »

20 Maritime pine occurs north of San Sebastian, in the Bay of Biscay area. The climate and site conditions in Galicia, Catalonia, Aragon and Andalusia are favourable to the walnut, which is currently present and may be assumed to have been so in the past (Gonzalez Vasquez 1947: 360). The black and white poplar (i.e. the indigenous species) occurs in the valleys of northern Spain, especially Catalonia (Gonzalez Vasquez 1947: p. 346). Chestnut is found in the indicated areas, which correspond with the mountain forests, but only in areas with siliceous soil (Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 209). Beech: the Arab invasion from the 8th to the 13th century profoundly altered the ancient physiognomy of the flora. First and foremost, the deforestation of large areas of Spain made the country more arid. Beech disappeared in many cases, to be replaced by Scots pine and, like fir, only survives in the mountains. It no longer occurs on a significant scale, except in the foothills of the Pyrenees and in certain small valleys, where it has been protected from destruction. Scots pine: sporadic species located below the zone of fir on the eastern foothills of the Spanish Pyrenees (Rubner and Reinhold 1953: 211). Thuja: Schmucker (1942) locates this species in the south of the Iberian Peninsula and in North Africa. Boudy (1950: 706, 707) places it more specifically in the Cartagena region. »