Cloth

Study based on historical texts and contracts

Recipes

‘These old masters when they laid the ground on their panels, fearing lest they should open at the joints, were accustomed to cover them all over with linen cloth attached with glue of parchment shreds, and then above that they put on the gesso to make their working ground.’1Vasari 1907: 224. The practical implementation of the work is explained at length by Vasari (1511–1574), Cennino Cennini (c.1370–c.1440), and in the contracts and orders agreed with painters. ‘When you have done the sizing’, Cennini writes, ‘take some canvas, that is, some old linen cloth, white threaded, without a spot of any grease. Take your best size; cut or tear large or small strips of this canvas; sop them in this size; spread them out over the flats of these anconas with your hands; and first remove the seams; and let them dry for two days.’2Cennini 1933: 70. Cloth, in the form of strips glued over the joins,3Requin 1908: 59. or pieces covering the entire surface of the panels, on both the front and back,4Chobaud 1939: 89, 105, 116. insulated the paint layer more effectively from the wood, while also providing the panels with better protection.

Contracts

Contracts dating from between 1403 and 1416 with the painter Luis Borrassà (1350–1424) in Barcelona likewise specify ‘that the said Luys shall size and cover with canvas’ all or part of the altarpieces.5Madurell Marimon 1950: 151, 156, 165, 213, 328. The contract dated 13 January 1518, in which the painter Pedro Nunyz is engaged to paint an altarpiece for the castle chapel at San Marçal, of which ‘the joins will be sealed with linen all around ... wherever this is necessary’,6Madurell Marimon 1944: 147. is the last to refer to the use of cloth. Contracts awarded to the same painter in Barcelona from 1527 to 1569 do not mention it, simply stating that the panel should be ‘filled, sealed and plastered’.7Madurell Marimon 1944: 180, 205, 233, 237.

Supplies

In October 1378, the duke’s8Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. painter Jean de Beaumetz (c.1335–1396) reimbursed ‘20 sous for chalk, varnish, and 5½ ells of cloth, used for a painting of the Virgin and Child with St John and Other Saints, by order of the duke and ... 2 francs for cloth, blanc de Paveille and paints, for an image of Our Lady for the Charterhouse at Lugny’.9Prost 1902–1913, II: nos. 239, 252. Linen was most commonly used, with hemp cloth mentioned just once in the receipts published by Monget: ‘10 ells of coarse hemp cloth to cover every part of the aforesaid frame, to protect it from rotting against the wall.’10Monget 1898: 209 (receipt dated 22 November 1389).

Linen, on the other hand, is mentioned frequently. A 1398 document states: ‘Jehan Malwel [Malouel], painter of Burgundy, is supplied with cloth with which to cover the panels he is to paint ... the large sheets he will use to protect his panels and tear into strips for the frames or borders.’ The receipt provided to the supplier of these materials on 4 September 1398, reads: ‘To Robin Gauthier, merchant, residing in Joingny, for the sale of 38 ells of white linen cloth, à fleur, delivered to Jehan Malwel, for use in covering several panels and altarpieces, and on which to paint several altars for the Carthusian church, at the price of 2 sols 11 deniers tournois per ell’. That same year, Robin Gauthier supplied the artist with a further ‘35 ells of linen cloth to make strips to put on the edges [ès lymandes] of the painting he is doing for the Carthusians’ chapterhouse’.11Monget 1898: 295, 314.

From Belot, the tixière (mercer), and Guilot Poissonier, both Dijon merchants, Jean Malouel purchased ‘6 large lengths of linen, each one three toilles wide ... to cover several panels and altarpieces ... and white linen cloth to cover also and to glue onto the aforesaid altars and panels, to prepare them for painting’.12Monget 1898: 296, 313. Theophilus, the monk, is more flexible, recommending ‘medium-weight new cloth’,13Editors’ note: Theophilus 1979: 27. which could be either linen or hemp. All the same, the results of the twenty-two microscopic analyses we performed confirm both Vasari’s indications and the information gleaned from artists’ contracts and quittances for the period in question.

Application to the panels

The samples taken from both the backs and fronts of the panels did indeed all turn out to be linen cloth. Hemp does not appear to have been used therefore on painting supports in this period. The overview at the end of this chapter includes a breakdown of the cloth found on the fronts and backs of some of the panels. We found textiles to be used more frequently on the front than on the back, while in some cases they were applied to both. Strips of cloth across joins are quite rare: it is most common for the cloth to cover the entire surface of the wood.

Theophilus makes a restriction: he advises the use of cloth, but only ‘if you lack hide’.14Editors’ note: Theophilus 1979: 27. Therefore as far as he is concerned, animal hide is the optimal material for this purpose. ‘Then the panels should be covered with the raw hide of a horse or an ass or a cow, which should have been soaked in water. As soon as the hairs have been scraped off, a little of the water should be wrung out and the hide while still damp laid on top of the panels with cheese glue.’15Editors’ note: Theophilus 1979: 26. Textile coverings are indeed replaced in some cases with parchment, which is what we assume Theophilus means by ‘hide’.16Editors’ note: Namur, Museum Gaiffier d’Hestoy, Annunciation of Walcourt, parchment on the joints; see Verougstraete-Marcq and Schoute 1989: 53. We found four panels covered with parchment in this way. Two of them are from the Aragonese School of the 13th and 14th centuries,17Front of the St John the Baptist Altarpiece (Painting index, no. 882); St Ursula Altarpiece (Painting index, no. 883). and are now in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, and there are also two by Albrecht Altdorfer (1488–1538) in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich: Danube Landscape near Regensburg and St George in the Forest.18Painting index, nos. 373 and 1003. The backs of these four panels are completely covered in parchment.

Fibres

Fibres are an important element in the preparation of panels for the Spanish and German schools.19Editors’ note: The method of securing joins by applying parchment and gluing horse or cow hair transversely to the join, while used mainly in the 15th and 16th centuries, also continued in the first quarter of the 17th century (Sonnenburg and Preusser 1979). The use of canvas as a reinforcing material for panels is documented into the 17th century. A premature conclusion regarding this should be avoided before thorough research has been carried out, since later paintings on canvas were glued onto panels – a conservation measure already practised by the 17th century. They are rare, however, in Italy, for which we only found one example – on the central panel of the St Zeno Altarpiece.20St Zeno Altarpiece: The Crucifixion, Musée du Louvre (Painting index, no. 695). The only textual references to their use occur in Spanish contracts. Orders placed in Barcelona and Malenyanes, between 1515 and 1541, with Pedro Nunyz and Enrique Fernández, state the following: ‘Use filler ... stop up the panels before painting them ... seal the joins, and all the flat surfaces.’21Madurell Marimon 1944: 147, 155, 166, 172, 205. The ‘filler’ in question will no doubt have been fibres. We found fifteen Spanish panels prepared in this way, distributed among the Catalan, Aragonese and Castilian schools of the 15th and 16th centuries, and fifteen German panels from the Upper Rhine, Bavarian, Tyrolean and Swabian schools of the 15th and 16th centuries. The fibres are found either in strips across the joints, as we can see on the back of the St Zeno Altarpiece, or across the entire surface, soaked in size or ground (enduit) (Fig. 109).

Of the fifteen German panels, eight have strips and seven are covered with fibres across the whole of their backs. Seven of the Spanish panels are completely covered, with four having only strips across the joints. Having been soaked in enduit, the fibres used for the German panels were sometimes painted, either in a solid colour or with a painted scene. The backs are treated in this way for the Portrait of Margrave Christopher of Baden by Hans Baldung Grien (c.1484–c.1545); Christ before Pilate by Master W.S. with the Maltese Cross; and Albrecht Altdorfer’s St George in the Forest and Susanna Bathing and the Punishment of the Slanderers. The paintings in question are in the museums of Munich and Strasbourg.22Munich, Alte Pinakothek (Painting index, nos. 1029, 1003 and 1004); Strasbourg, Musée des Beaux-Arts (Painting index, no. 1036).

What distinguishes the Spanish from the German schools, however, is the presence or otherwise of fibres on the front of the panels. As far as we know, there are no German panels with fibres beneath the painted layer on the front. On the other hand, these are found in Spain as we were able to confirm at the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona on numerous Catalan and Castilian panels.23Attributed to Francisco de Comontes, St Martin (Painting index, no. 903); attributed to Pedro Espalargues, Male and Female Saints (Painting index, no. 895); Joan Gascó, St Sebastian and St Martial, Bishop (Painting index, no. 488); Pedro Nunyz, St Eligius Altarpiece (Painting index, nos. 470–475). Fibres are found in these instances on both sides of the panel.

It is evident from this brief survey that the use of fibres in Spain was chiefly a feature of the Catalan and Castilian schools (Barcelona, Lleida and Toledo) and that it is not found prior to the 15th century. It may be concluded, therefore, that the Spanish schools initially used cloth and parchment interchangeably. However, while use of the latter ceased in the 14th century, cloth continued to be employed, with fibres making their appearance in the 15th century. Those German schools that use this technique – the Upper Rhine and Bavaria in particular – only do so, moreover, on the front of the panels.

Nature of the fibres

The fibres used on panels take the form of strips of varying width, held in place and fixed to the wood by enduit. They can be of plant or animal origin (Figs 16–22), the former including linen and hemp. The results of the fibre analyses we performed break down as follows:

•Plant fibres: hemp 9; linen 1

•Animal fibres:24The only example of animal fibres we found came from the school of Parma. The work in question is Parmigianino’s Portrait of an Artist (?) (Florence (Galleria degli Uffizi), Painting index, no. 700). There are likely to be other examples – certainly in Italy and probably in Germany. The information we gathered at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich suggests that this is indeed the case. Unfortunately, we were unable to obtain samples of fibre at this museum in order to provide scientific confirmation. horsehair 1

Glues

‘Beginning to work on panel, in the name of the Most Holy Trinity: always invoke that name and that of the Glorious Virgin Mary’, Cennino Cennino wrote. The first step, he said, is to make the ‘various sorts of size’.25Cennini 1933: 65. He then gives recipes for these different types of glue, which are used for a range of purposes: fish glue, goat glue, parchment clippings and soft cheese for ‘making lutes, tarsias, fastening pieces of wood and foliage ornament together, tempering gessos, doing raised gessos; and it is good for many things’,26Cennini 1933: 67.

A 14th-century manuscript, Dehaisnes writes,27Dehaisnes 1886, II: 559. contains a detailed description of a size made with softened cheese, which was used to join the various parts of a wooden painting. He is no doubt referring to Cennino Cennini’s Il libro dell’arte, paragraph CXII, of which contains instructions for making a glue out of lime and cheese for use by master carpenters. The cheese is soaked in water to soften it, then mixed with a little quicklime. The resulting glue joins pieces of wood and ‘fastens them together well’.28Cennini 1933: 68. Cennini also gives a recipe for ‘a perfect size for tempering gessos for anconas or panels’. It is made from clippings of parchment, washed thoroughly and boiled ‘until the three parts are reduced to one’. He declares that ‘you cannot get any better one anywhere’ and advises his reader, ‘when you have no leaf glue, I want you just to use this size for gessoing panels or anconas.’29Cennini 1933: 67–8. In Huguenin Le Vicaire’s receipt made out in Dijon on 21 January 1391 there is a reference to parchment clippings to be supplied to the duke’s painter, Jean de Beaumetz, for use in sizing the altarpieces and the paintings that each of the said Carthusians must have in his cell.30Prost 1902–1913, II: no. 3,776.

Size clearly played a crucial role in both the construction and the protection of the panels. Painters were, for instance, ‘required to size’ the altarpieces in the contracts; they were asked to ‘undertake to size’ and to make ‘all necessary preparations, sealing the panels, which shall be well sized’; and it was specified that they would ‘first plaster the panel and then seal it all over with plaster and strong glue’.31Madurell Marimon 1944: 155, 166, 172, 180, 205; 1950: 89, 91, 114, 156.

Having completed this examination of the nature and the composition of the coatings and other elements related to the preparation process, we are left with a sense of uniformity and the certainty that the nature of the enduit does not reflect the choice of wood used to construct the support.

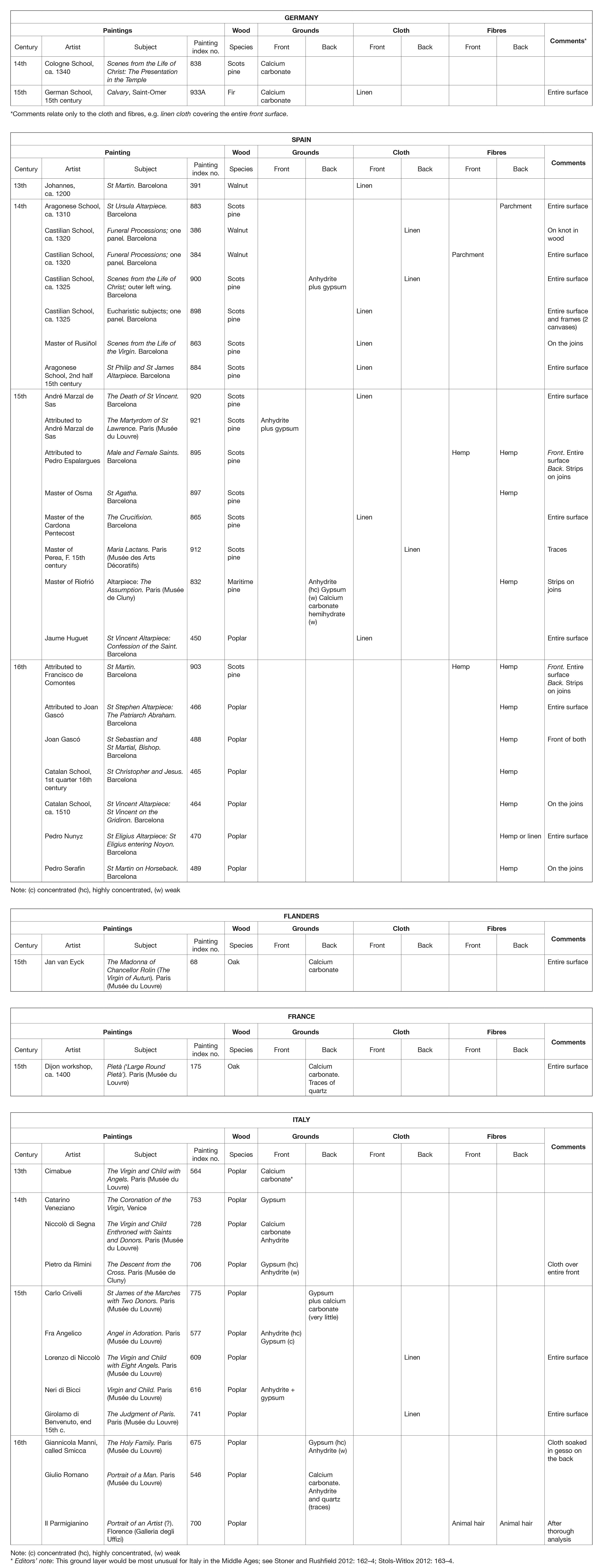

Overview of coatings, fibres, cloth and parchment on the front and back of a number of panels

1 Vasari 1907: 224. »

2 Cennini 1933: 70. »

3 Requin 1908: 59. »

4 Chobaud 1939: 89, 105, 116. »

5 Madurell Marimon 1950: 151, 156, 165, 213, 328. »

6 Madurell Marimon 1944: 147. »

7 Madurell Marimon 1944: 180, 205, 233, 237. »

8 Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. »

9 Prost 1902–1913, II: nos. 239, 252. »

10 Monget 1898: 209 (receipt dated 22 November 1389). »

11 Monget 1898: 295, 314. »

12 Monget 1898: 296, 313. »

16 Editors’ note: Namur, Museum Gaiffier d’Hestoy, Annunciation of Walcourt, parchment on the joints; see Verougstraete-Marcq and Schoute 1989: 53. »

17 Front of the St John the Baptist Altarpiece (Painting index, no. 882); St Ursula Altarpiece (Painting index, no. 883). »

19 Editors’ note: The method of securing joins by applying parchment and gluing horse or cow hair transversely to the join, while used mainly in the 15th and 16th centuries, also continued in the first quarter of the 17th century (Sonnenburg and Preusser 1979). The use of canvas as a reinforcing material for panels is documented into the 17th century. A premature conclusion regarding this should be avoided before thorough research has been carried out, since later paintings on canvas were glued onto panels – a conservation measure already practised by the 17th century. »

21 Madurell Marimon 1944: 147, 155, 166, 172, 205. »

22 Munich, Alte Pinakothek (Painting index, nos. 1029, 1003 and 1004); Strasbourg, Musée des Beaux-Arts (Painting index, no. 1036). »

23 Attributed to Francisco de Comontes, St Martin (Painting index, no. 903); attributed to Pedro Espalargues, Male and Female Saints (Painting index, no. 895); Joan Gascó, St Sebastian and St Martial, Bishop (Painting index, no. 488); Pedro Nunyz, St Eligius Altarpiece (Painting index, nos. 470–475). »

24 The only example of animal fibres we found came from the school of Parma. The work in question is Parmigianino’s Portrait of an Artist (?) (Florence (Galleria degli Uffizi), Painting index, no. 700). There are likely to be other examples – certainly in Italy and probably in Germany. The information we gathered at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich suggests that this is indeed the case. Unfortunately, we were unable to obtain samples of fibre at this museum in order to provide scientific confirmation. »

25 Cennini 1933: 65. »

26 Cennini 1933: 67. »

27 Dehaisnes 1886, II: 559. »

28 Cennini 1933: 68. »

29 Cennini 1933: 67–8. »

30 Prost 1902–1913, II: no. 3,776. »

31 Madurell Marimon 1944: 155, 166, 172, 180, 205; 1950: 89, 91, 114, 156. »