If we refer to guild regulations, we find that these went as far as to specify a particular type of wood for a particular type of job. Paris guild regulations stated in 1260, for instance, that: ‘Coopers working in Paris may only make barrels in one of four ways ... that is to say using heartwood oak without sapwood, pear, whitebeam, or maple.’1Boileau 1879: 103–4. These conditions could vary, however, at the customer’s request. Article 6 of the statutes of the Abbeville painters and sculptors, in 1508, stated that ‘works belonging to the said guild of woodcarvers will be of good oak or bois d’irlande’ unless the customers themselves preferred ‘elm or walnut with no trace of rotten wood’.2Thierry 1835: 343.

Using certain varieties of wood together was also prohibited. The regulations of the carpenters and joiners’ guild in Angers set out the following prohibition in 1487: ‘The said carpenters and joiners shall not use nor be compelled to place white wood with oak in their work, but will use oak with oak, white wood with white wood, and walnut with walnut.’3Ordonnances des rois de France, vol. XX, p. 17. Municipal regulations in Noyon state a similar type of requirement in 1398: ‘Anyone who makes chests, boxes, and benches may make them from oak and walnut together, and may make a bench with a frame in any wood, except for sapwood and bad wood [morbois], and all joints must be free of sapwood.’4Fons 1841: 23, note.

The species of wood used for the secondary elements of the support frequently differed, in fact, from that chosen for the support. The contract awarded in Barcelona on 15 October 1569 to the craftsman Martin Diez de Liatzasolo (ca. 1500–1583), who was to make a St Steven Altarpiece, which Pedro Nunyz would then paint for the parish church in Castellar, details the different types of wood that could be used: ‘Shall make a Retablo de San Esteban in good wood ... with regard to the wood with which the said Master Martin shall make and build the said altarpiece, it shall be various [divers], that is to say, the columns in cypress, the friezes and carvings of all the said altarpiece should be in very resinous pine or in cypress, and all the flat surfaces and mouldings should be in poplar, all this in good wood.’5Madurell Marimon 1944: 233.

Another contract agreed in Barcelona on 11 August 1534 between the sculptor Joan de Tours and the Fraternity of San Miguel de los Carniceros, to construct an altarpiece for their chapel, likewise states that ‘the altarpiece will be made of wood with six figures carved in cypress ... the main part will be in poplar as will the top, and the flat surfaces in pine from Valencia or Tortosa’.6Madurell Marimon 1944: 237. For another example, see p. 170 (P. Nunys, Barcelona, 29 April 1538).

Different species of wood

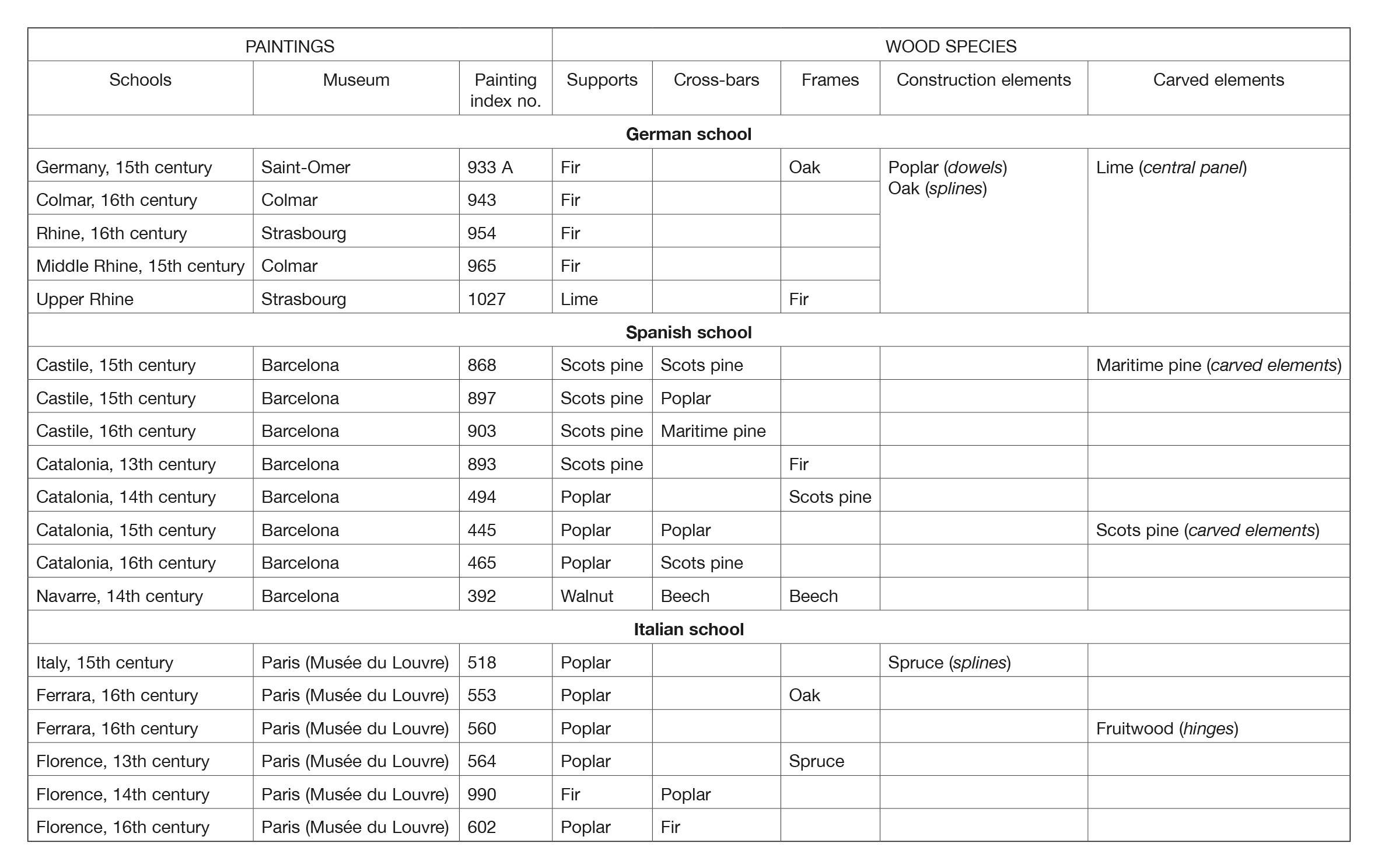

Like the carved elements of the panel, the cross-bars, dowels and frames are all frequently made of a different species of wood than the panel.

In the same support

The boards making up a support are not always the same species of wood. Although this is very rare, an example is found in the Nice School around 1500 and in the Catalan School in the first third of the 16th century. The first of these examples is the most interesting: it is the Virgin and Child with St Peter and St Paul in the Musée Masséna,7Nice school, 16th century (Painting index, nos. 367 and 986). which consists of five boards, four spruce and one fir. Examination of the painting leaves no doubt, however, as to its authenticity. A 16th-century Catalan panel8Joan Gascó, Scene of Invalids at the Tomb of a Saint, Barcelona (Painting index, no. 383). is likewise constructed using several different species of wood.

In the same ensemble

It is more common to find panels made of different woods combined within a triptych. In Italy, an example can be found in the 14th-century triptych9Venice (Painting index, nos. 535, 1049 and 1050). in which the central panel and right wing are limewood and the left wing poplar. The difference in wood type is particularly significant here: unlike the Masséna Virgin and Child panel, it is not different varieties of the same species that are used, but different species altogether.10We did not include this triptych in our chapter on anomalies as the wood varieties used in these panels are local ones. Similarly, the two wings from the School of Raphael in the Louvre showing Abundance and the Small Holy Family were painted on walnut in one case and poplar in the other.11Painting index, nos. 432 (walnut) and 541 (poplar). These panels do not constitute an anomaly for Italy, either, since the types of wood in question existed locally. Once again, however, the difference between the species of wood used is so large that the paintings deserve, in our view, a particularly close examination.

Similar cases are found in Spain, in the Catalan School of the 12th–14th century. To cite a particular example, the polyptych with the Virgin Mary and the Three Kings in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, painted in 1150,12Painting index, nos. 478, 479, 480 and 481 (poplar), and 62 and 63 (oak). is made up of six panels, two of which are painted on poplar and four on oak. Similarly, the two side panels of an altarpiece in the same museum, showing St Paul and St Peter with Four Angels, painted in Lleida around 1200, are on Scots pine and poplar respectively.13Painting index, nos. 490 (poplar) and 890 (Scots pine).

Two examples of panels painted on fir and spruce are from Central Germany. These are the two panels by the Master of the Altarpiece of the Regular Canons from the town of Erfurt, in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, showing the Presentation of Mary in the Temple and the Death of the Virgin.14Painting index, nos. 972 (fir) and 355 (spruce). The two panels of Jan Polack’s (1450–1519) altarpiece from the Bavarian School, representing St Corbinian and the Bear and the Death of St Corbinian,15Toire, nos. 935 (fir) and 323 (spruce). are likewise painted on spruce and fir.

In France, the Master of the Aix Annunciation painted the central panel of the Annunciation Altarpiece on poplar, the right wing on spruce and the left wing on fir.16Central panel, Eglise de la Madeleine, Paris (Painting index, no. 502); right wing, Brussels (Painting index, no. 362); left wing, Amsterdam (Painting index, no. 983). Louis Bréa (ca. 1450–ca. 1523) likewise used two different varieties of softwood to paint the predella and the side panels of the St Margaret Altarpiece in Luceram.17Painting index, nos. 363 and 364 (spruce), and 984 and 985 (fir). These panels belong to the Musée Masséna in Nice. The central panel, which is still in the church at Luceram, has not been studied.

On 22 October 1505, Canon Louis Quinet of Cavaillon agreed to the terms of a contract for an altarpiece for the church at Mazan, specifying to the carpenter and joiner Jean Vial (Vialis), also from Cavaillon, that the corpus should be in white poplar and the outer parts in walnut.18Chobaut 1939: 99. Antonio Ronzen similarly undertook on 3 May 1512 to make an altarpiece, the central panels (lo plan) of which would be in poplar and the rest in fir.19The contract for this painting reads as follows: ‘Antonio Ronzen, painter and sculptor of Venice, residing in Aix and Marseille, undertakes on 3 May 1512 to paint in the Charity of Sainte-Tulle, in the church of that place, in Cucuron, and to make an altarpiece dedicated to the Saint … measuring 1 canne high, 7 palms wide’; Chobaut 1939: 124. And on 28 May 1520, Manuel Genovese agreed to make and paint an altarpiece for the Fraternity of St Eligius in Cucuron. The body of the altarpiece, in walnut, was to be nine and a half palms high (including the predella) and as wide as the altar of St Eligius. The back and the predella were to be made of white wood.20Chobaut 1939: 106.

In the secondary parts

Considerable diversity is found in the choice of wood species, both in different countries and within the same school. Poplar, Scots pine and maritime pine, for instance, are used interchangeably in Spain to make cross-bars for the supports, and fir, Scots pine and beech for frames. Likewise in Italy, fir or poplar was used for cross-bars and species as different as oak and spruce for frames. Different types of wood were also used in Germany to construct the frames and dowels for panels. There does not appear, therefore, to have been any rule governing the choice of wood type used in the secondary elements. It was evidently left up to the woodworkers or artists themselves. To illustrate this, we have set out several examples of this diversity in Table 1.

Table 1 Wood species used for the secondary elements of the support.

Wood of the same species

Although contracts often specify a different species of wood for the construction of the secondary elements of a support, these instructions are not systematic. It is also frequently the case that contracts, while specifying the nature of the wood, only mention a single species.21See ‘Extracts from painters’ contracts’ for the nature of the wood used for the supports according to painters’ contracts. There are many examples of panels of this kind in medieval Europe, where the support, reinforcements and frame are all made of the same wood. An example is Melchior Broederlam’s altarpiece for the Chartreuse at Champmol.22Dijon (Painting index, nos. 185 and 186). The central panel, carved by Jacques de Baerze (active before 1384–died after 1399), is made of oak, as is the support of the wings and the frame. The frame and support of the Venasque Altarpiece23Avignon School, 15th century (Painting index, nos. 407–409). in the Musée Calvet in Avignon are walnut; the frame and support of the Parisian panels painted around 1380–90 making up the Small and Large Bargello Diptychs24Florence (Museo Nazionale del Bargello) (Painting index, nos. 202–205). are in oak; and the cross-bars, frames and supports of the four Aragonese panels from the 13th to the 15th century in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya in Barcelona are made of Scots pine.25Barcelona, Aragonese School, 13th century, St John the Baptist Altarpiece (Painting index, no. 882); 14th century, St Ursula Altarpiece (Painting index, no. 883); St Philip and St James Altarpiece (Painting index, no. 884); 15th century, The Coronation of the Virgin (Painting index, no. 861). Lastly, the secondary elements of the four 12th–14th-century Catalan panels in the same museum are made of poplar, like the support itself.26Catalan School, 12th century, Christ, the Apostles and St Martin (Painting index, no. 878); 13th century, Christ Pantocrator and Apostles (Painting index, no. 891); Episodes from the Life of St Peter (Painting index, no. 892); 14th century, Eucharistic subjects (Painting index, no. 898). There is no general rule, therefore, but only specific cases. All the same, we noted a higher frequency of panels executed with different species of wood.

We would like to conclude by noting the presence of iron in panels from the Catalan School. This material, which was used for cross-members, contributed to the construction and reinforcement of the panels. The six panels by Pedro Nunyz that comprise the St Eligius Altarpiece in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya in Barcelona27Painting index, nos. 470–475. are reinforced by iron cross-members recessed into the wood across the width of the panels.

1 Boileau 1879: 103–4. »

2 Thierry 1835: 343. »

4 Fons 1841: 23, note. »

5 Madurell Marimon 1944: 233. »

6 Madurell Marimon 1944: 237. For another example, see p. 170 (P. Nunys, Barcelona, 29 April 1538). »

10 We did not include this triptych in our chapter on anomalies as the wood varieties used in these panels are local ones. »

16 Central panel, Eglise de la Madeleine, Paris (Painting index, no. 502); right wing, Brussels (Painting index, no. 362); left wing, Amsterdam (Painting index, no. 983). »

17 Painting index, nos. 363 and 364 (spruce), and 984 and 985 (fir). These panels belong to the Musée Masséna in Nice. The central panel, which is still in the church at Luceram, has not been studied. »

18 Chobaut 1939: 99. »

19 The contract for this painting reads as follows: ‘Antonio Ronzen, painter and sculptor of Venice, residing in Aix and Marseille, undertakes on 3 May 1512 to paint in the Charity of Sainte-Tulle, in the church of that place, in Cucuron, and to make an altarpiece dedicated to the Saint … measuring 1 canne high, 7 palms wide’; Chobaut 1939: 124. »

20 Chobaut 1939: 106. »

21 See ‘Extracts from painters’ contracts’ for the nature of the wood used for the supports according to painters’ contracts. »

25 Barcelona, Aragonese School, 13th century, St John the Baptist Altarpiece (Painting index, no. 882); 14th century, St Ursula Altarpiece (Painting index, no. 883); St Philip and St James Altarpiece (Painting index, no. 884); 15th century, The Coronation of the Virgin (Painting index, no. 861). »

26 Catalan School, 12th century, Christ, the Apostles and St Martin (Painting index, no. 878); 13th century, Christ Pantocrator and Apostles (Painting index, no. 891); Episodes from the Life of St Peter (Painting index, no. 892); 14th century, Eucharistic subjects (Painting index, no. 898). »