Grounds

Study based on historical texts and contracts

Formulas

André Félibien, writing in his Entretiens sur les vies et sur les ouvrages des plus excellens peintres, advises artists who wanted their works to last for a long time to pay due attention to applying a durable ground and to use colours that do not fade. It is true, he concedes, that artists ‘are not always free to choose the grounds for their paintings, being obliged to work sometimes on plaster, sometimes on wood, and often on canvas ... yet it is always within their power to take great care in preparing the different grounds’.1Félibien 1725: 9.

The preparation of grounds was indeed the focus of the greatest possible care. Cennino Cennini does not leave out a single detail. He dwells at length on the making of gesso grosso and gesso sottile, on their respective use, and their application to wooden panels.2It is useful to read paragraphs CXV, CXVI, CXVII, CXVIII, CXIX, CXX and CXXI on the preparation of wooden panels in Part Six of The Craftsman’s Handbook ‘Il Libro dell’Arte’ by Cennino Cennini (translated by Daniel V. Thompson, Jr.), New Haven 1933 (repr. New York 1960), pp. 70–74. Without explaining how to make the grounds themselves, Theophilus, the monk, nevertheless recommends taking ‘some gypsum burned in the fashion of lime (or some of the chalk-white with which skins are whitened) ... grind it carefully ... when it is dry spread a little more on thickly ... when it is completely dry ... rub the white [surface] until it is completely smooth and bright’.3Editors note: Theophilus 1979: 27.

Contracts

The advice of these early authors appears to have been followed in the contracts. Around the time Cennino Cennini was writing his invaluable Craftsman’s Handbook and roughly two centuries after Theophilus’ curious work Diversarum artium schedula, a contract was agreed in Barcelona, on 20 January 1396, between the priest Joan Humiach and the painter Luis Borrassà (1350–1424). The latter was to ‘cover with coarse plaster and fine plaster’, as good craftsmanship required, the altarpiece he was to paint for the church of Sant Joan de Valls, a dependency of Tarragona.4Madurell Marimon 1950: 114. On 26 January 1402, the same painter was contracted to ‘size and coat with good plaster, coarse and fine’, the altarpiece he was to paint for the Chapel of the Incarnation at Santa Maria church in Copons.5Madurell Marimon 1950: 143.

Contracts dating from 1403, 1404, 1414 and 1415 further specify that the painter Luis Borrassà should properly cover the panels in fine plaster, ‘providing all the layers necessary’, that he ‘shall make all other necessary preparations for the said work ... the parts and the whole will be covered ... that he shall also cover all the flat surfaces, and likewise that he will cover all the rest ... the statues will be prepared with coarse plaster and fine plaster’.6Madurell Marimon 1950: 151, 156. Somewhat later, on 27 August 1534, Master Enrique Fernández was contracted in turn to paint the altarpiece for the Chapel of St Onophrius at the Augustine abbey in Barcelona, on a panel covered with fine plaster. The contract specifies that he should devote ‘the care that the said work deserves’.”7Madurell Marimon 1944: 166.

Similar requirements are expressed in the contracts granted to the painter Pedro Nunyz by the hospital of St Severus in Barcelona on 14 March 1541 and the parish of Sant Genís dels Agudells (Horta) on 31 October 1552. It is specified here that all the images (carvings) in these altarpieces ‘shall be covered in coarse plaster and fine plaster’, and that the painter ‘shall cover and fill the piece as a whole with plaster and strong size’.8Madurell Marimon 1944: 172, 180.

Material: chalk

Monget’s publication of receipts dating from 1390 to 1396 for goods purchased on behalf of the Chartreuse at Dijon provides information in particular regarding the nature of the materials used to prepare wooden panels: ‘To Huguenin le Vicaire, of Dijon, for the sale of 350 pounds of chalk [craie] to cover the altarpieces of the church of the Chartreuse and the paintings [tableaux] that each of the said Carthusians must have in his cell, since the eighth day of August 1390, at the price of 1 franc 8 gros per hundred.’9Monget 1898: 199. Another receipt relating to Guiot Poissonnier, a merchant of Dijon, states: ‘He provided Malwel [Malouel] for the painting of several panels and altarpieces ... chalk [craie], [??] glue [glux de noe] on which to paint.’10Monget 1898: 313. These receipts also give us an insight into the practical execution of the work: ‘To Huguenin Lavoignier, plasterer [torchour], for twenty-two days’ work done by him and his father ... to prepare the ground for the altarpiece of His Grace the Duke of Berry.’11Monget 1898: 296. According to Labarte, white chalk helped preserve the freshness of the colours, but could be detrimental to the adhesion and elasticity of the paint layer.12Labarte 1864–1866, II: 559. Editors’ note: This comment seems somewhat misleading given current knowledge, since most northern panel paintings and altarpieces from the 14th to the end of the 16th century were executed on chalk grounds (see Stols-Witlox 2014).

Application to the panel

Preparing the front and back

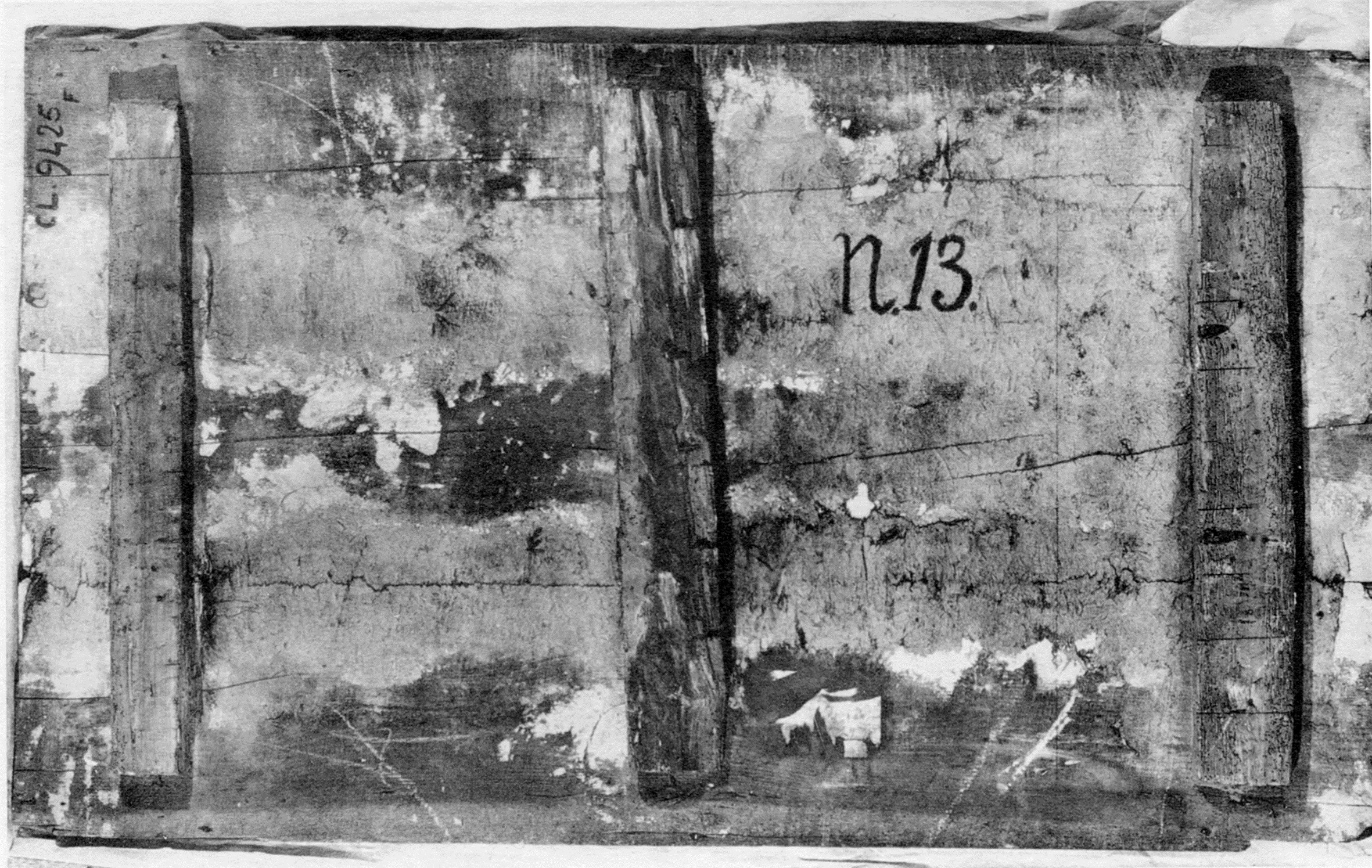

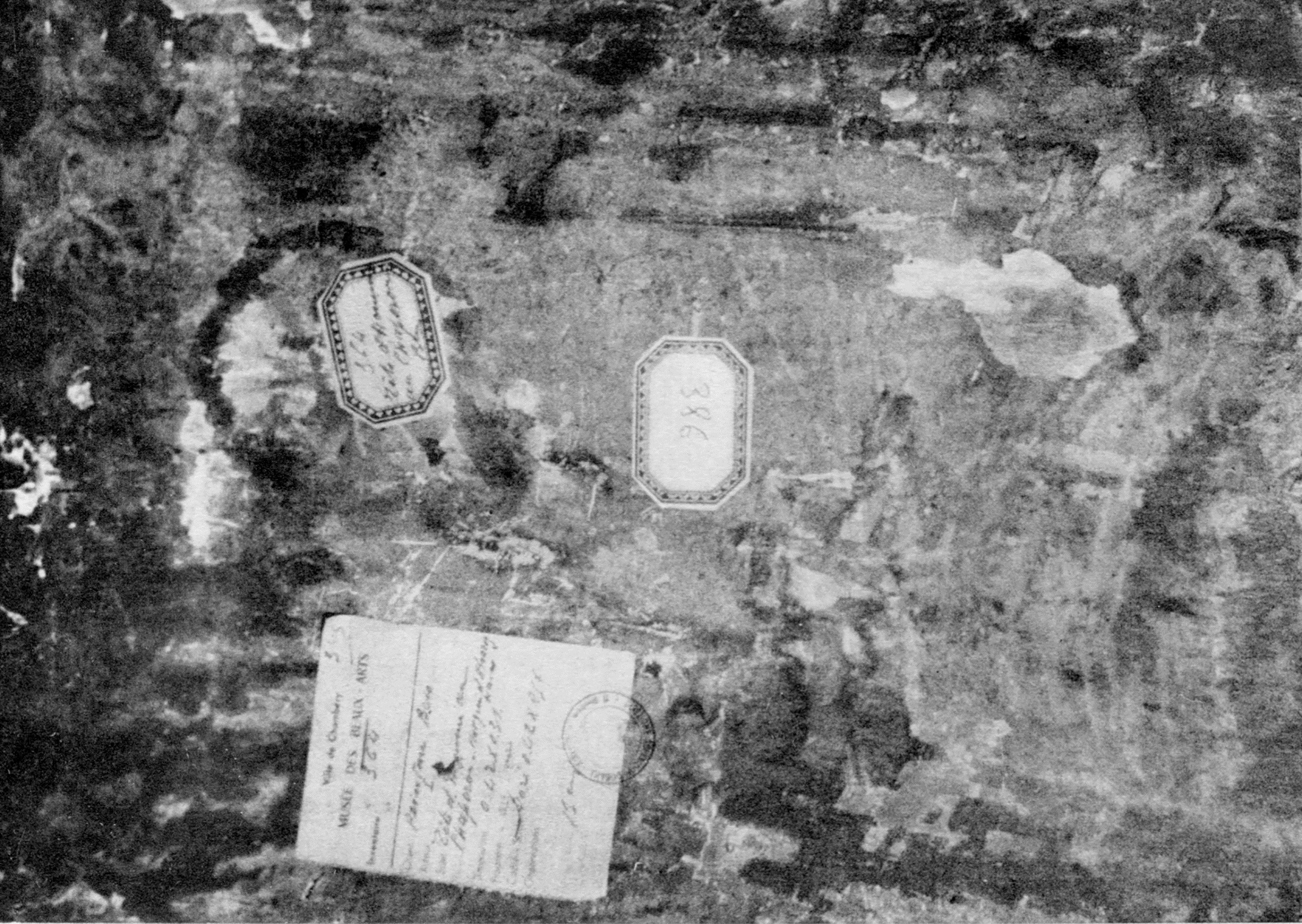

It appears that the backs of panels were at first mostly coated for protection. We counted over a hundred panels from every school and every era with grounds that remain intact. On the backs, as in the Portrait of a Young Man in the Musée de Chambéry by Paolo Uccello (Fig. 134); that of the Coronation of the Virgin by Jacopo di Cione (ca. 1325–after 1390) (Fig. 93); and the altarpiece panels by the Master of Riofrió in the Musée de Cluny (Fig. 133). Some of these traces are more visible than others, but they are extremely common on the backs of the panels. For the most part, they are very thick. Since they were not intended as the ground for a painting, these coatings covered the back of the entire panel. In some cases they are simple, while in others they are mixed with additional materials, such as fibres or cloth, and may or may not have been painted.

We noted that in Germany, in particular, most panels painted on both sides have virtually no ground layer on the reverse side. Examples include the Visitation by the Master of the Guebwiller Altarpiece13Guebwiller Triptych (Painting index, no. 331). in the Museum of Strasbourg; the Resurrection from Hans Pleydenwurff’s (ca. 1420–1472) Hof Altarpiece and the Beheading of John the Baptist attributed to Martin Schongauer (ca. 1448–1491) in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich;14Painting index, nos. 950 and 332. several panels from the Passion Altarpiece by the workshop of Martin Schongauer;15Colmar (Painting index, nos. 333–345). St Conrad of Constance by the Master of the Coburg Roundels (active ca. 1470–1500) in the Museum of Strasbourg;16Strasbourg (Painting index, no. 970). and the Crucifixion by the School of Martin Schongauer and St Ursula and her Companions from the Rhine School, in the Museum of Colmar.17Colmar (Painting index, nos. 937 and 959).

It is interesting to note that these paintings mostly belong to the Rhine schools. The preparation of the backs of these panels is so minimal that the cut and grain of the wood can be seen beneath the paint layer, which is itself very thin. This way of preparing the backs of panels for painting is not always found, however, on the fronts of the same supports, many of which have been given a much thicker ground layer. The fronts of the panels, unlike the backs, always have a ground layer, the thickness of which varies considerably. It is generally substantial in the case of the Spanish schools, and thin for the German18It is interesting to note that The Ascension in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Besançon (Painting index, no. 436), which was formerly attributed to the German school, had been an exception to these findings. Its reattribution to the Spanish school confirms our observations. and Portuguese schools.19Editors’ note: Considerable research has since been done on the composition, preparation and application of ground layers, as well as on practices associated with medieval workshops and the division of labour; see Federspiel 1995; Nadolny 2008; Stols-Witlox 2012.

For the most part, grounds in France, as in the Northern countries, are sufficiently substantial to conceal any trace of either the grain of the wood or the method used to cut the boards. The layers in question are neither as fine as those found on Portuguese panels nor as thick as those in Spain. The two paintings from the Loire School, dating from around 1460, showing the Virgin and Child with St Benedict and the Adoration of the Magi,20Le Mans, Musée de Tessé (Painting index, nos. 177 and 178). are exceptions to this pattern. Indeed, both these paintings were executed almost directly onto the wood. The paint layer is so thin that the cut of the wood is clearly visible beneath it.

There is little question, therefore, of deriving a fixed rule. In addition to varying from one school to another, the thickness of the preparatory layers also reflects the relevant period. It is therefore reasonable to postulate a relationship between the amount of ground and the period in which the painting was done. However, since this relationship cuts across that with the individual school, it is impossible to draw any conclusions from it.

Chemical composition of the grounds

All these grounds shared the same characteristics in the Middle Ages, whether they were used on the front or back of the support or on the mouldings of the frame. They were whitish in colour and there was little variation in terms of their chemical composition. We initially thought that the species of wood might have influenced the nature, composition and thickness of the grounds. One might expect, for instance, that the resin found in certain varieties would be exploited as a natural means of protection, thus reducing the need for a preparatory coating. Our study showed, however, that there is no evidence of this at all, and that no relationship appears to exist between the nature of the ground and that of the wood. In no case did we find, for example, that resinous softwood supports were given thinner grounds; on the contrary, there were many examples of oak panels with virtually no preparatory coating, especially among the Portuguese schools. The overview at the end of this study illustrates the lack of any correspondence between the chemical composition of the grounds and the type of wood used to construct the supports.

The grounds break down into two categories: plaster and chalk:21See X-ray crystallography analysis in Chapter 1.

•Plaster grounds (gypsum + anhydrite): if the plaster is prepared correctly and allowed to set, the result is pure gypsum, CaSO4.2H2O. If, however, the plaster is overheated during preparation, rather than forming hemihydrate CaSO4. ½H2O22Editors’ note: CaSO4.2H2O + heat → CaSO4.½ H2O + 1½ H2O. (which, as it rehydrates, sets and again forms gypsum), complete dehydration occurs and anhydrite (or anhydrous calcium sulphate, CaSO4) is formed, which does not hydrate. The result is a mixture of CaSO4 and CaSO4.2H2O (Figs 23–26).

•Chalk grounds23Analysis of the ground on the back of Van Eyck’s The Madonna of Chancellor Rolin (The Virgin of Autun), detected the presence of a tin oxide (SnO2) in addition to chalk. We note this purely for information purposes, as the question of pigments falls beyond the scope of our study. (calcium carbonate: CaCO3): calcium carbonate can come from recarbonation of lime on exposure to the air or to the presence of chalk in the initial ground (Figs 27–29).

Historical processes for making grounds

The presence of coarse and fine plaster of chalk, as mentioned by early authors and in Spanish contracts, and that of gypsum, as mentioned by Labarte in his Histoire des arts industriels au moyen âge,24Labarte 1864–1866, II: 559. is confirmed by analysis of the grounds found on the panels. These grounds were obtained in the Middle Ages through a fairly unreliable heating procedure. Since it was not possible to check the temperature of the ovens, heating was frequently uneven. The plaster obtained in this way therefore comprised a mixture of anhydrite and gypsum. Anhydrite formed at a temperature of around 300°C/572°F cannot rehydrate, and so plaster of this kind contains a certain amount of anhydrous sulphate produced by the overheating of the plaster (Figs 23 and 25, in particular).

We had hoped that chemical analysis of these plasters might provide an additional means of identifying paintings through comparison with analysis of plaster from a later period. If there had been a major advance in oven technology at the end of the Middle Ages, which improved the manufacture of plaster, it would indeed have been possible to distinguish between grounds (des plâtres) from different periods, thus providing art historians with a significant new tool. Sadly, this is not the case: 17th- and 18th-century ovens were every bit as primitive as those of earlier centuries. We have to wait until the latter part of the 19th century (after 1860) for the emergence of modern kilns, which altered the manufacture of plaster and its chemical composition.25Information provided by Prof. A. Guinier of the Sorbonne (Laboratoire des Rayons X, at the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers) and published with his kind permission. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to him.

It is not possible, therefore, to distinguish analytically between plaster made in the 14th century and that produced in the early 19th century.26This type of plaster is no longer produced now, except in Germany, where a product called ‘flooring plaster’ is manufactured, with the same properties as the old plaster. This is not, however, the result of imperfect heating as in the past, but is made with a specific view to obtaining these properties. Only the appearance of other characteristics, such as colour, allow distinctions to be made.

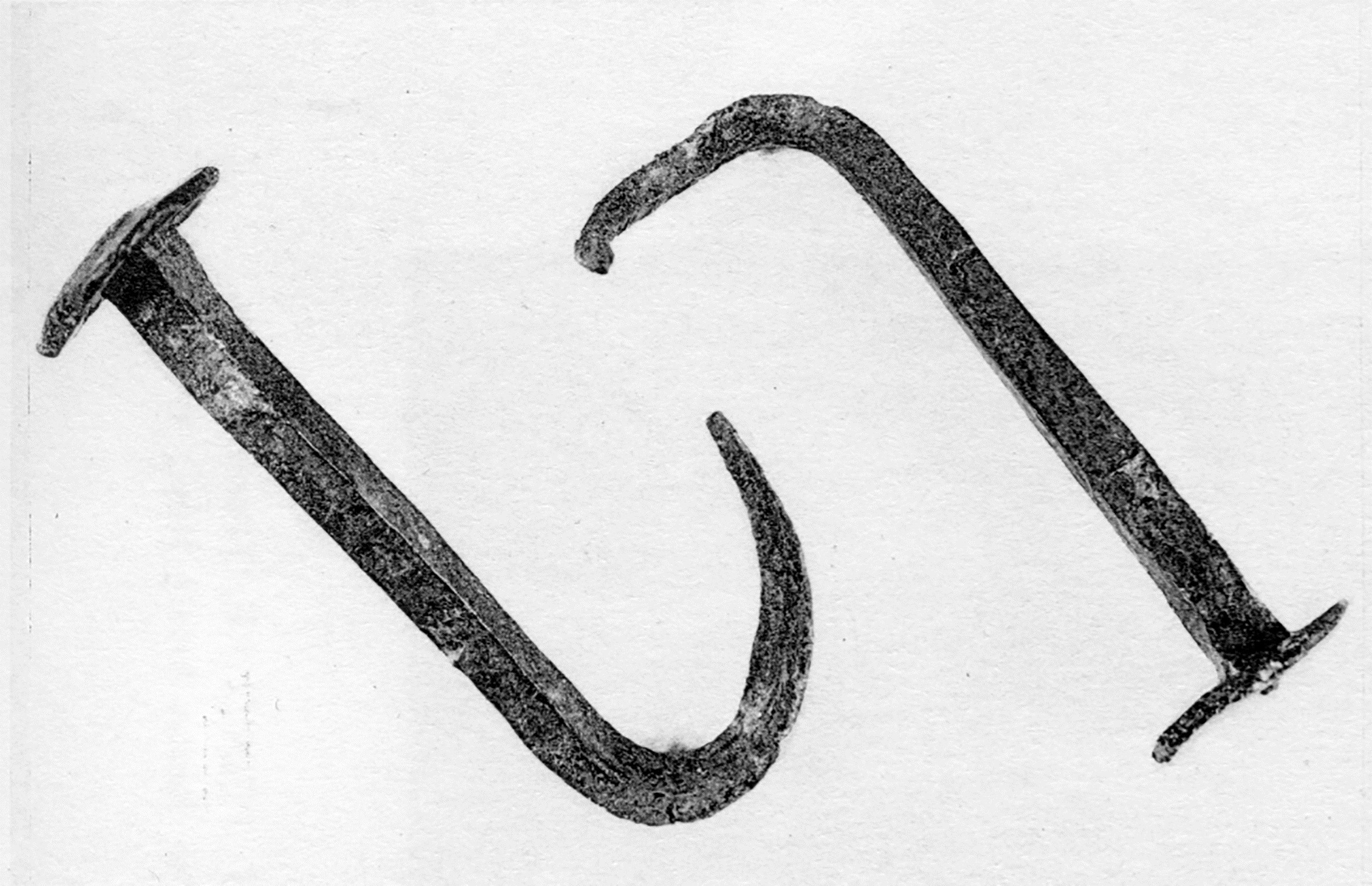

Figure 129 Nails used for fixing cross-bars to the panel. (Pascual Ortonéda, The Death of St Anthony. Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Post 1930–1953, VI : 602–4, fig. 266, scale 2:3.)

Figure 130 Reinforcing nails driven in from the edge of the panels. (Francesco Francia, Christ on the Cross. Paris, Musée du Louvre. Painting index, no. 561, scale 1:2.)

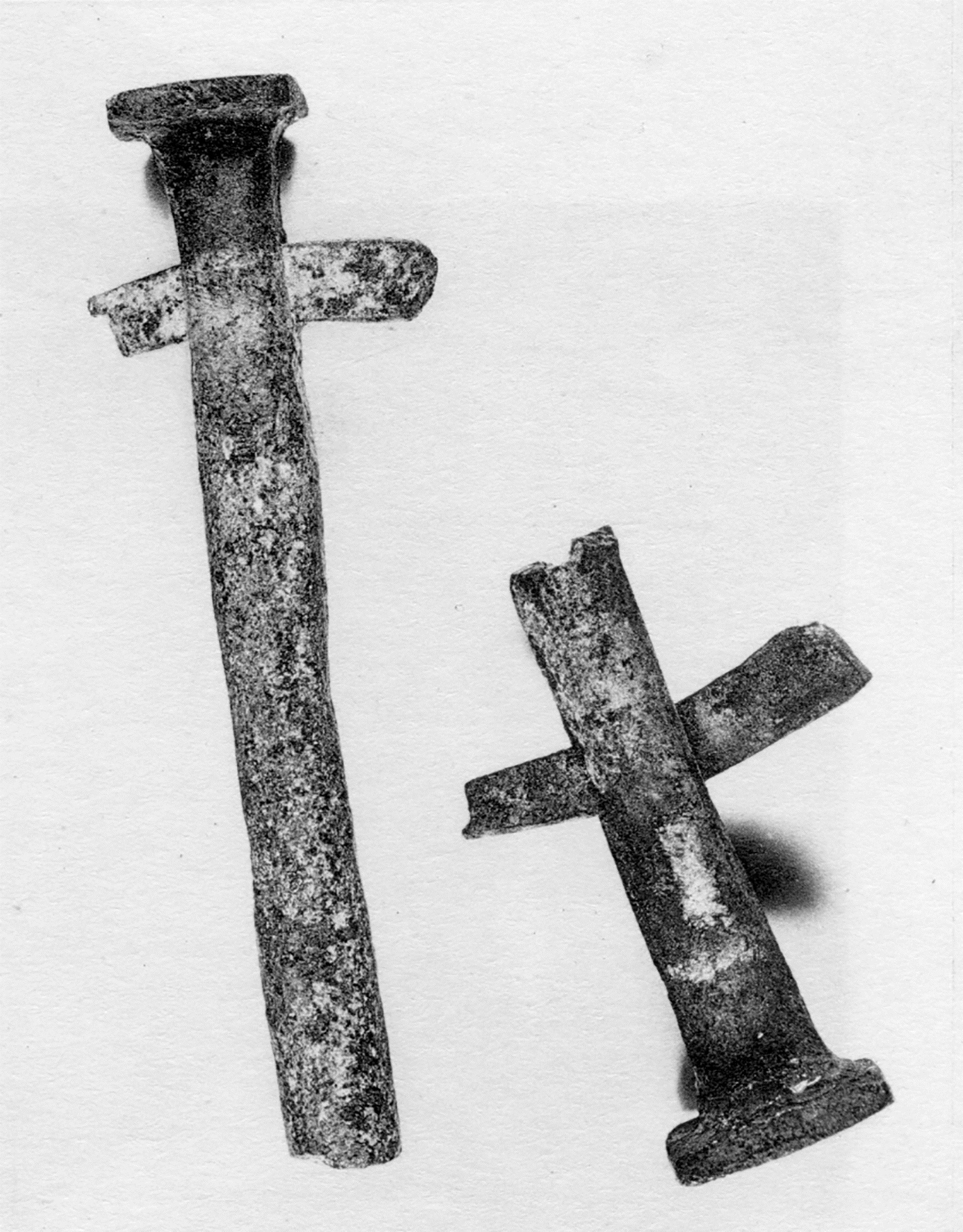

Figure 131 Peg used for fixing cross-bars to the panel. (Antonio Ronzen, Altarpiece of the Passion. Saint-Maximin, Dominican church. Painting index, no. 418, scale 1:2.)

Figure 132 Dowels used for fixing a cross-bar to the panel. (Vasco Fernandez, Creation of the Animals. Lamego, Museum. Painting index, no. 312.)

Figure 133 Protection of joins: ground and fibre. (Master of Riofrió, Altarpiece: The Crucifixion. Paris, Musée de Cluny. Painting index, no. 831.)

Figure 134 Protection of the back: ground and fibre. (Paolo Uccello, Portrait of a Young Man. Chambéry, Musée des Beaux-Arts. Painting index, no. 630.)

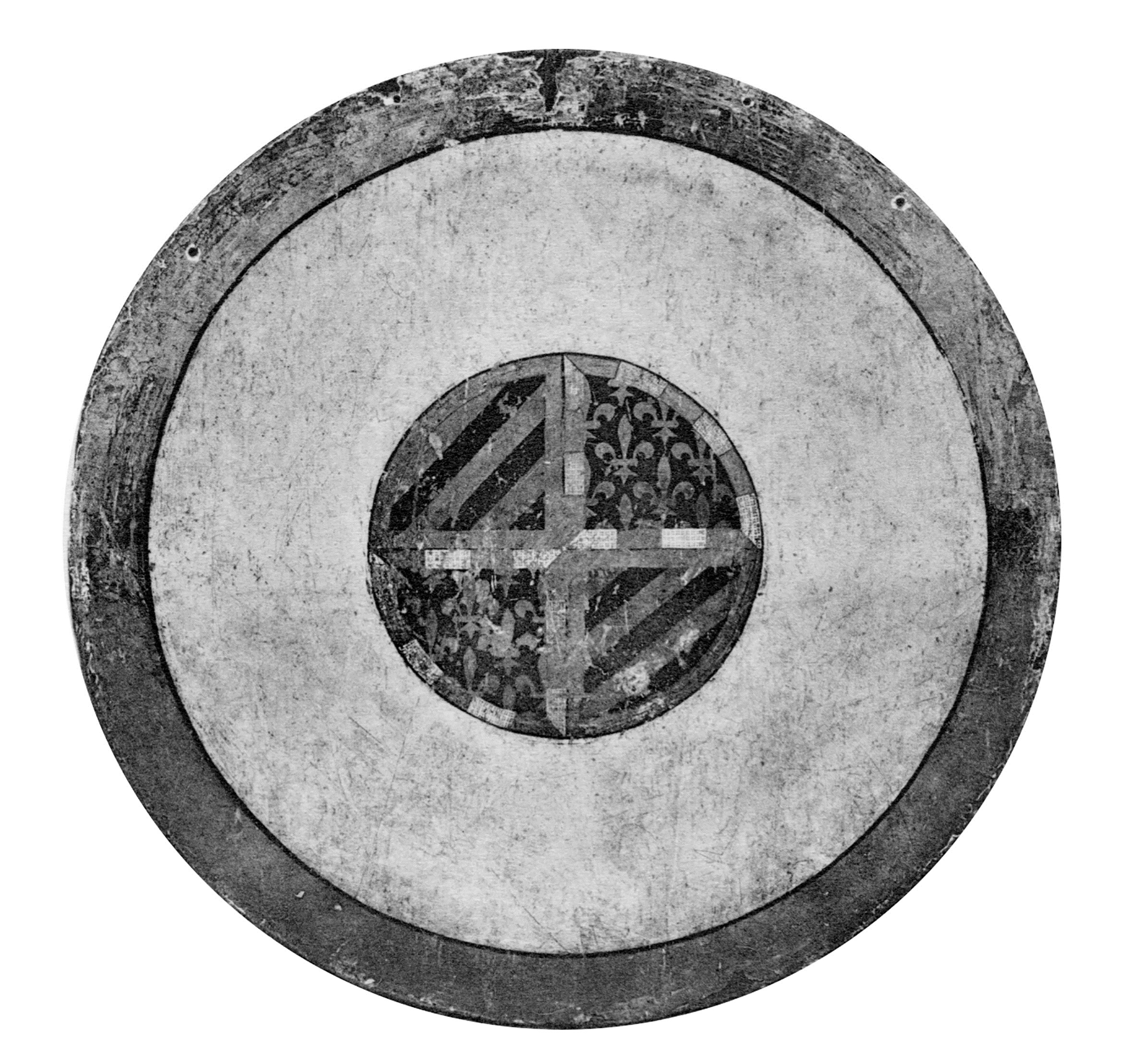

Figure 135 Panel painted on both sides. (Dijon workshop, c.1400, Pietà, known as the Large Round Pietà. Back. Paris, Musée du Louvre. Painting index, no. 175.)

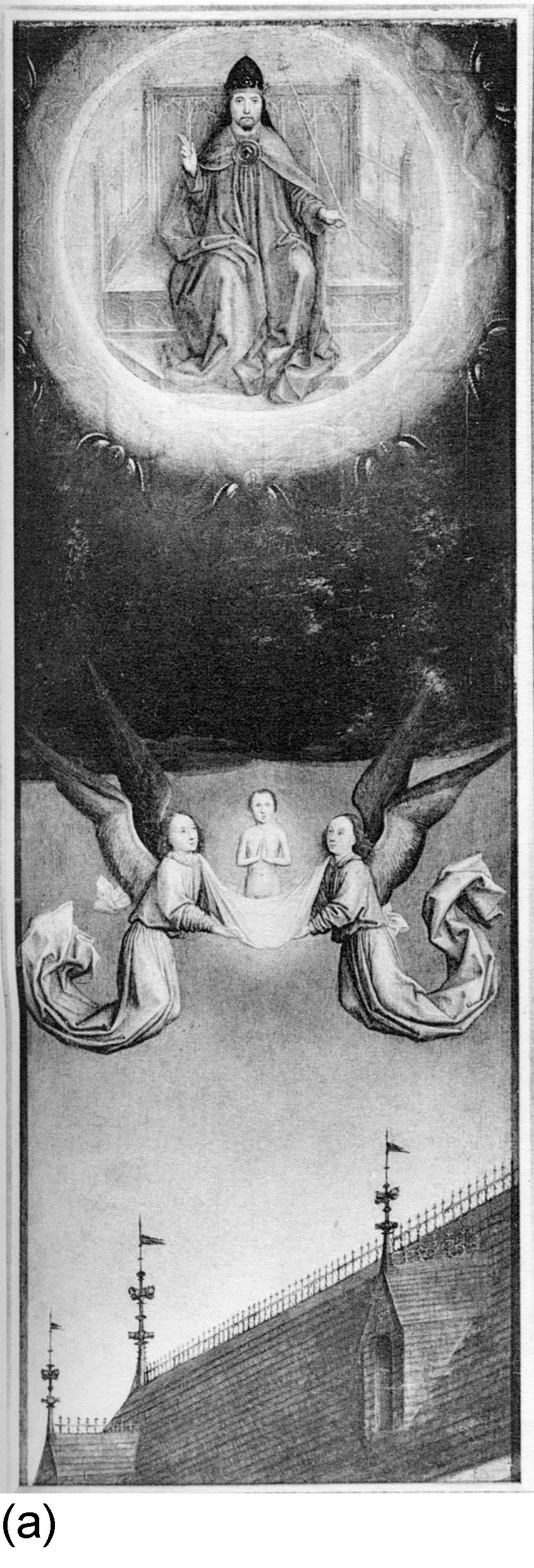

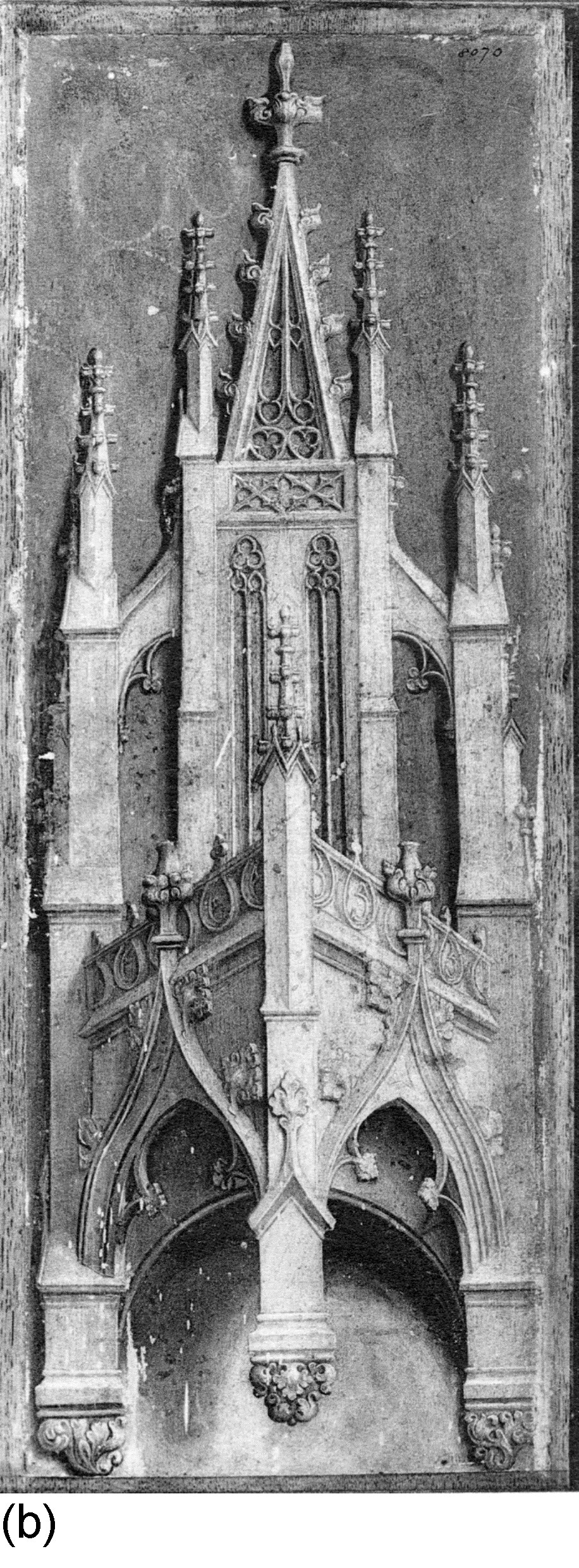

Figure 136 Panel painted on both sides. (Simon Marmion, St Bertin Altarpiece. Fragments. (a) Front: The Soul of St Bertin Carried up to God. (b) Back: Gothic canopies. London, National Gallery. Painting index, nos. 197 and 198.)

Figure 137 Dust guard. (School of Juan Rexach, 15th century, The Virgin Surrounded by Saints. Details; upper left part. Marseille, Comte de Demandolx-Dedons Collection. Painting index, no. 925.)

Panels painted on both sides

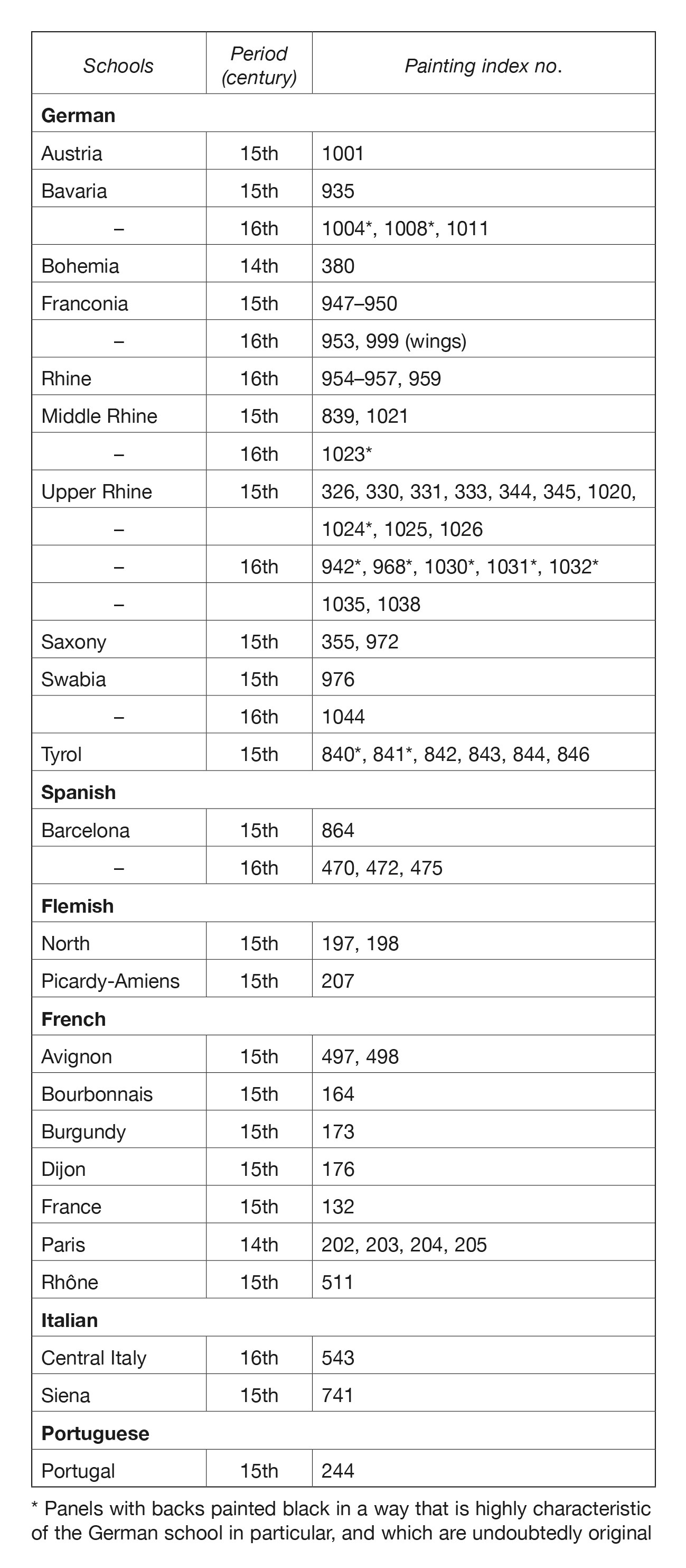

We are only concerned here with the painting of the backs of panels as a form of protection. Table 1 lists the schools that used this technique. We have deliberately left out examples of painting consisting solely of colourwashing, which could have been redone or restored more recently. Instead, we exclusively considered panels with backs painted in the form of a scene (Fig. 136b), a decorative motif (see the Preface), or a coat of arms (Fig. 135). These come primarily from Germany,27We found a number of panels belonging to Rhine schools, especially that of the Upper Rhine, which are painted black with either a grey Maltese cross or red dots over the entire surface, something highly characteristic of this school. Flanders, and France. Labande recorded the presence at the Papal Palace in Avignon of an altarpiece, the whereabouts of which are no longer known, showing ‘various images painted on both sides’.28Labande 1932, II: 243.

Table 1 Schools using the technique of painting of the backs of panels as a form of protection.

It was undoubtedly the fact that these panels were intended for use in altarpieces that caused them to be painted on both sides: this should not be interpreted as a technique for preserving the wood.29Editors’ note: Goetghebeur 1996. All the same, painting in this way did offer protection, as these panels are generally well preserved.30Editors’ note: The backs of some panels may still have their original ground, generally of the same material as that used on the front (Wadum 1998a).

1 Félibien 1725: 9. »

2 It is useful to read paragraphs CXV, CXVI, CXVII, CXVIII, CXIX, CXX and CXXI on the preparation of wooden panels in Part Six of The Craftsman’s Handbook ‘Il Libro dell’Arte’ by Cennino Cennini (translated by Daniel V. Thompson, Jr.), New Haven 1933 (repr. New York 1960), pp. 70–74. »

4 Madurell Marimon 1950: 114. »

5 Madurell Marimon 1950: 143. »

6 Madurell Marimon 1950: 151, 156. »

7 Madurell Marimon 1944: 166. »

8 Madurell Marimon 1944: 172, 180. »

9 Monget 1898: 199. »

10 Monget 1898: 313. »

11 Monget 1898: 296. »

12 Labarte 1864–1866, II: 559. Editors’ note: This comment seems somewhat misleading given current knowledge, since most northern panel paintings and altarpieces from the 14th to the end of the 16th century were executed on chalk grounds (see Stols-Witlox 2014). »

18 It is interesting to note that The Ascension in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Besançon (Painting index, no. 436), which was formerly attributed to the German school, had been an exception to these findings. Its reattribution to the Spanish school confirms our observations. »

19 Editors’ note: Considerable research has since been done on the composition, preparation and application of ground layers, as well as on practices associated with medieval workshops and the division of labour; see Federspiel 1995; Nadolny 2008; Stols-Witlox 2012. »

23 Analysis of the ground on the back of Van Eyck’s The Madonna of Chancellor Rolin (The Virgin of Autun), detected the presence of a tin oxide (SnO2) in addition to chalk. We note this purely for information purposes, as the question of pigments falls beyond the scope of our study. »

24 Labarte 1864–1866, II: 559. »

25 Information provided by Prof. A. Guinier of the Sorbonne (Laboratoire des Rayons X, at the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers) and published with his kind permission. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to him. »

26 This type of plaster is no longer produced now, except in Germany, where a product called ‘flooring plaster’ is manufactured, with the same properties as the old plaster. This is not, however, the result of imperfect heating as in the past, but is made with a specific view to obtaining these properties. »

27 We found a number of panels belonging to Rhine schools, especially that of the Upper Rhine, which are painted black with either a grey Maltese cross or red dots over the entire surface, something highly characteristic of this school. »

28 Labande 1932, II: 243. »

30 Editors’ note: The backs of some panels may still have their original ground, generally of the same material as that used on the front (Wadum 1998a). »