The durability of panels was just as much a concern to the artists of the period as the choice of wood and assembly of the boards. Vasari described the consequences of a poorly prepared support: ‘Whether the heat was excessive or the wood badly joined or ill-seasoned, the picture unfortunately split at the joints.’1Editors’ note: Vasari et al. 2005: 385. Vasari describes the method of applying canvas or linen to the panels before grounding and painting them. In his description, the linen not only had the advantage of covering unevenness and joints in the board but also offered a good grip for the ground (Berger 1901).

A similar preoccupation with the construction and preparation of supports is evident in contracts awarded to Pedro Nunys and Enrique Fernandez, in which these aspects are specified in detail. The contract agreed on 26 January 1402, under which the painter Luis Borrassà (ca. 1360–1425) was to supply an altarpiece for the Chapel of the Incarnation at the Santa Maria church in Copons, states that: ‘the support of the said altarpiece shall be made of good poplar, well seasoned and properly fitted with cross-bars’. Another contract with the same painter, dated 21 February 1403, further specifies that the altarpiece should be ‘properly fitted with cross-bars’ and ‘properly nailed’. Contracts from 29 August 1404, 18 April 1407, 17 April 1415 and 10 December 14162Madurell Marimon 1950: 143, 151, 156, 165, 218, 328. likewise contain a whole series of stipulations concerning the nature and quality of the wood.3Editors’ note: Cennino Cennini (ca. 1437) advised his fellow Italian painters to take some canvas or white-threaded old linen cloth, soak strips of it in sizing, and spread it over the surface of the panel or ancona; see Cennini 1859: ch. 114: ‘Come si dè impannare in tavola’ (‘How to put a cloth on a panel’). They describe in detail the system for reinforcing new ‘altar panels’. The construction of a painting support thus seems to have been inconceivable in Spain without the use of cross-bars for reinforcement.4Editors’ note: See Véliz 1998a. Antwerp altars more than 2 m high required the back to be secured by transverse battens – one at the neck, with more behind the main corpus. This requirement was incorporated in a new set of rules received by the Antwerp guild of Saint Luke on 20 March 1493 (Van Der Straelen 1855: 30–35).

We will briefly examine the different ways of strengthening supports that we have encountered, including strips of cloth or fibre placed across the joins, frames, and all manner of cross-members.

Panel reinforcements

Strips of linen and fibre

Strips of cloth were glued over the joins between the boards on the back and in many cases even on the front of the panels, where they simultaneously protected the join and strengthened the assembly. According to Abbé H. Requin, the Boulbon Altarpiece was painted on ‘wood covered with a light preparatory layer across its entire surface and strips of fabric three or four centimetres wide across the joins in the wood’.5Requin 1908: 9; 1904: 18 (the Boulbon Altarpiece has since been transposed). Both Spanish and French texts make frequent reference to this aspect of panel construction. In 1518, the artist Pedro Nunyz undertook to paint an altarpiece for the Chapel of San Marçal: ‘painted on panel ... the altarpiece will be caulked, the joins will be sealed with cloth all around ... wherever this is necessary’.6Madurell Marimon 1944: 147.

The panels we were able to list come from the Spanish, French, Italian, and German schools, although the first of these accounts for a significant percentage of the total. Within the Spanish School, almost all the panels come from Catalonia. They include two 13th-century antependia representing The Pantocrator and the Twelve Apostles and Scenes from the Life of St Andrew, painted on Scots pine, and several poplar panels painted by the Master of San Vicente dels Horts (active 13th century) around 1350 and by Jaume Huguet (1412–1492) around 1455–56, to mention only the most typical. Lastly, we also note the Profession of St Vincent Ferrier from the School of Jacomart Baçó (ca. 1410–1461) in Valencia on Scots pine, the St Quiricus and St Julietta Altarpiece by Pere Garcia de Benabarre (1445–1485) on poplar, and the Dream of a Pope on maritime pine from the mid-15th-century Spanish School.7The above paintings correspond with the following numbers in the Painting index: 891, 873, 441, 448–454, 904, 445–447 and 823.

Strips of fibre are even more common in Spain. We have found many examples by studying contracts awarded to Spanish painters, backed up by examination of their panels. The contract agreed with Pedro Nunyz in 1518 stipulates the use of cloth to seal the joins, but it also specifies that the altarpiece is to be ‘caulked’. Slightly later contracts with the same painter8Madurell Marimon 1944: 155, 166, 205. likewise recommend ‘placing caulk in all the joins on the front and back surfaces’. Terms such as ‘caulk’ and ‘seal’ indicate the use of fibres. All these bands of fibre take more or less the same form: they are generally soaked in enduit (the ground material) and then glued to the support. There are also numerous Spanish panels showing the caulking mentioned in the contracts, especially from Catalonia from the 16th or late 15th century.9Painting index, nos. 461–464, 465, 489 and 922. Bands of fibre to reinforce the joins are less common, but are found in Germany. The central panel of Dürer’s (1471–1528) Paumgartner Altarpiece in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich,10Painting index, no. 1017. for instance, displays eight strips of fibre that we assume to be original. The back of the Portrait of a Clergyman in the same museum, attributed to Mathis Gothardt-Neithardt (1475–1528), known as Grünewald, on which strips of linen and fibre alternate, is also curious.11Painting index, no. 1023.

Cross-bars

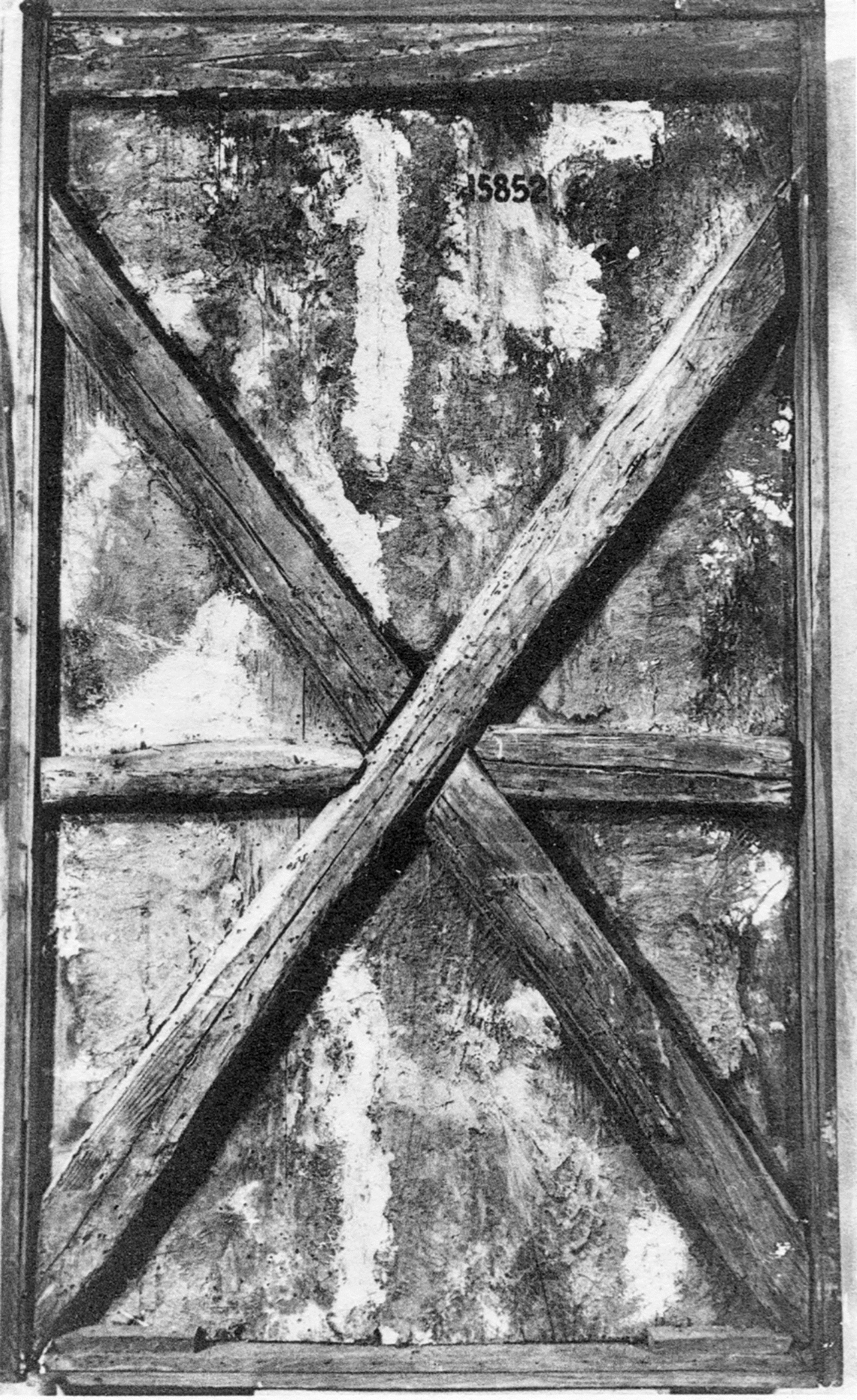

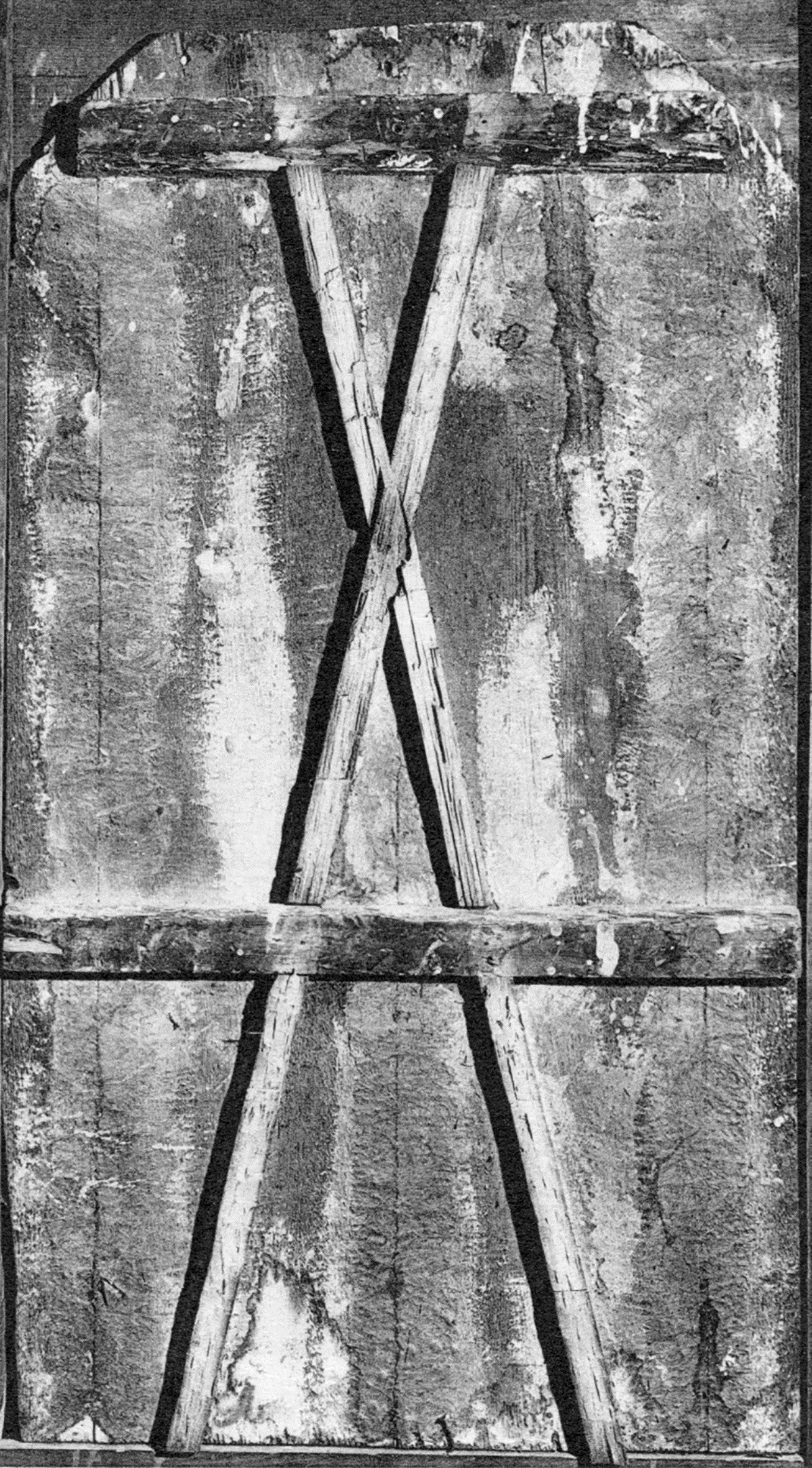

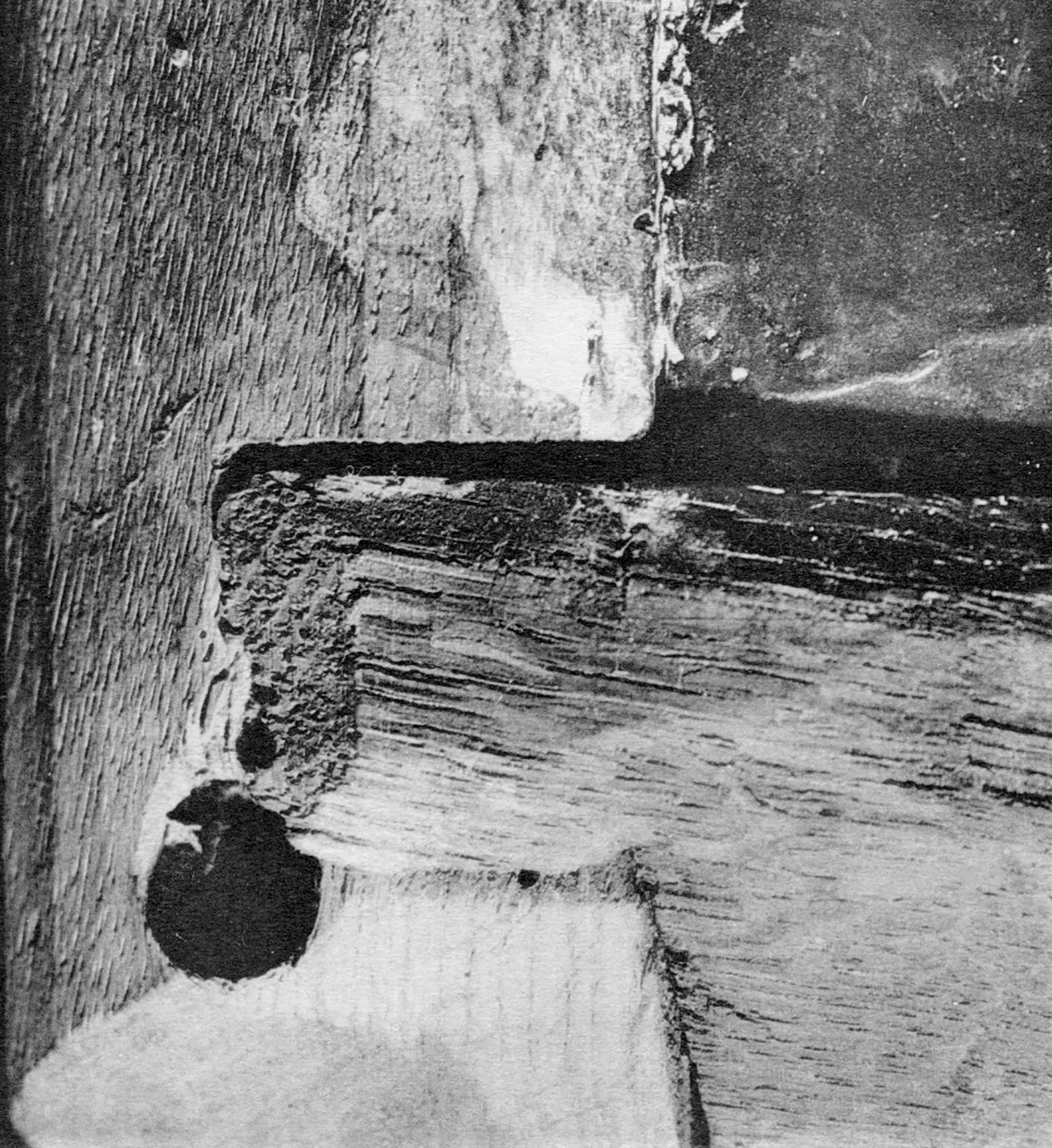

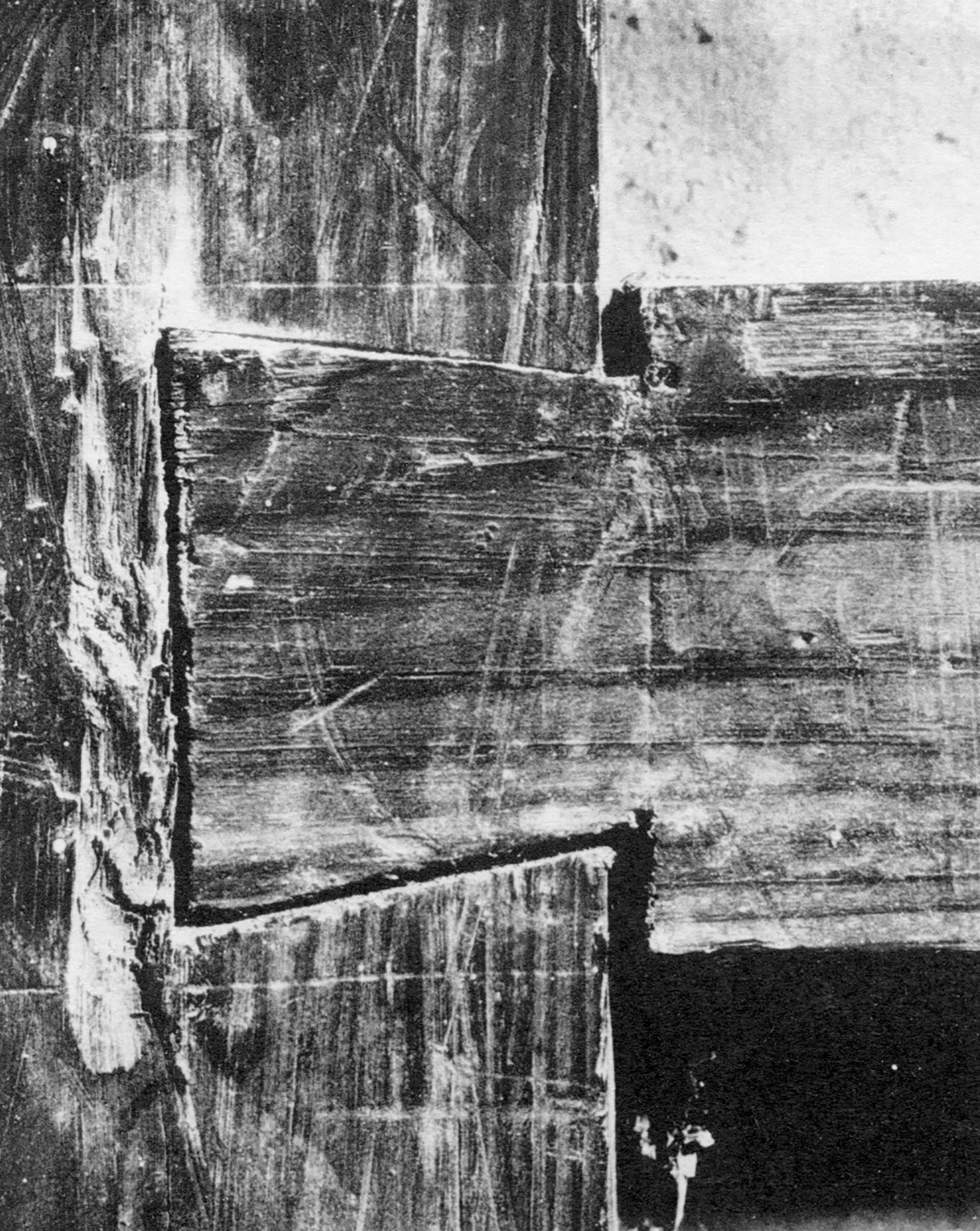

The use of cross-bars to reinforce the support is the oldest and most common technique employed in all the countries: ‘in addition to the wood being of good quality ... the panels will also have good cross-bars ... by which they will be properly held firm or secured’.12Madurell Marimon 1950: 151, 156, 165, 328. They are attached to the surface or deeply recessed – generally perpendicular to the grain – either without further reinforcing elements or with strips of linen or fibre, and fixed using nails driven through the front of the panel (Fig. 101), the points of which are clinched over on the cross-bar at the back of the panel (Fig. 102).

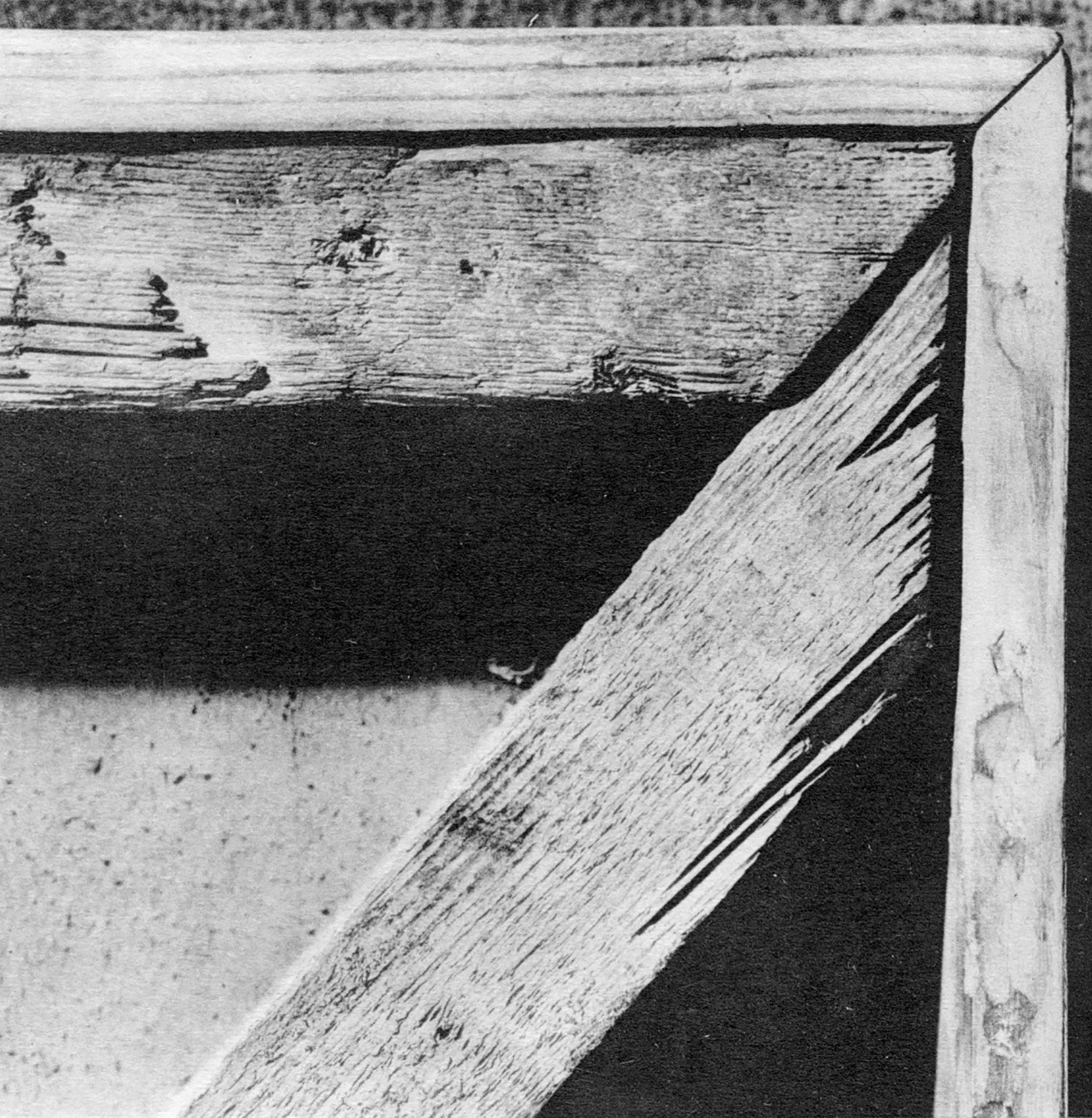

Surface-mounted cross-bars are the oldest. They can be applied without prior preparation of the support (Fig. 112), or can be applied to an area lightly thinned down in the area of the cross-bar (Fig. 100). There are numerous examples of panels reinforced like this with cross-bars. They are found in every school from the 12th to the 16th century. We noted, however, that cross-bars fitted onto thinned wood are less common in the 12th century, suggesting that this method is more recent than the others.13Editors’ note: Verougstraete-Marcq and Schoute 1989: 53.

Cross-bars recessed into the wood appear later. The dovetail on the back of Leonardo da Vinci’s Virgin and Child with St Anne (Fig. 124), for instance, is fixed into place without wooden dowels or iron nails. Cross-bars were generally straight up until the 16th century, but from that period onward, we also found numerous examples of tapering members. These are fitted across the back of the panels in opposite directions (Fig. 103).14Editors’ note: See the study of a late 16th-century Castilian altarpiece including a complete technical documentation of the altarpiece in all its aspects.

Diagonal braces and cross-bars

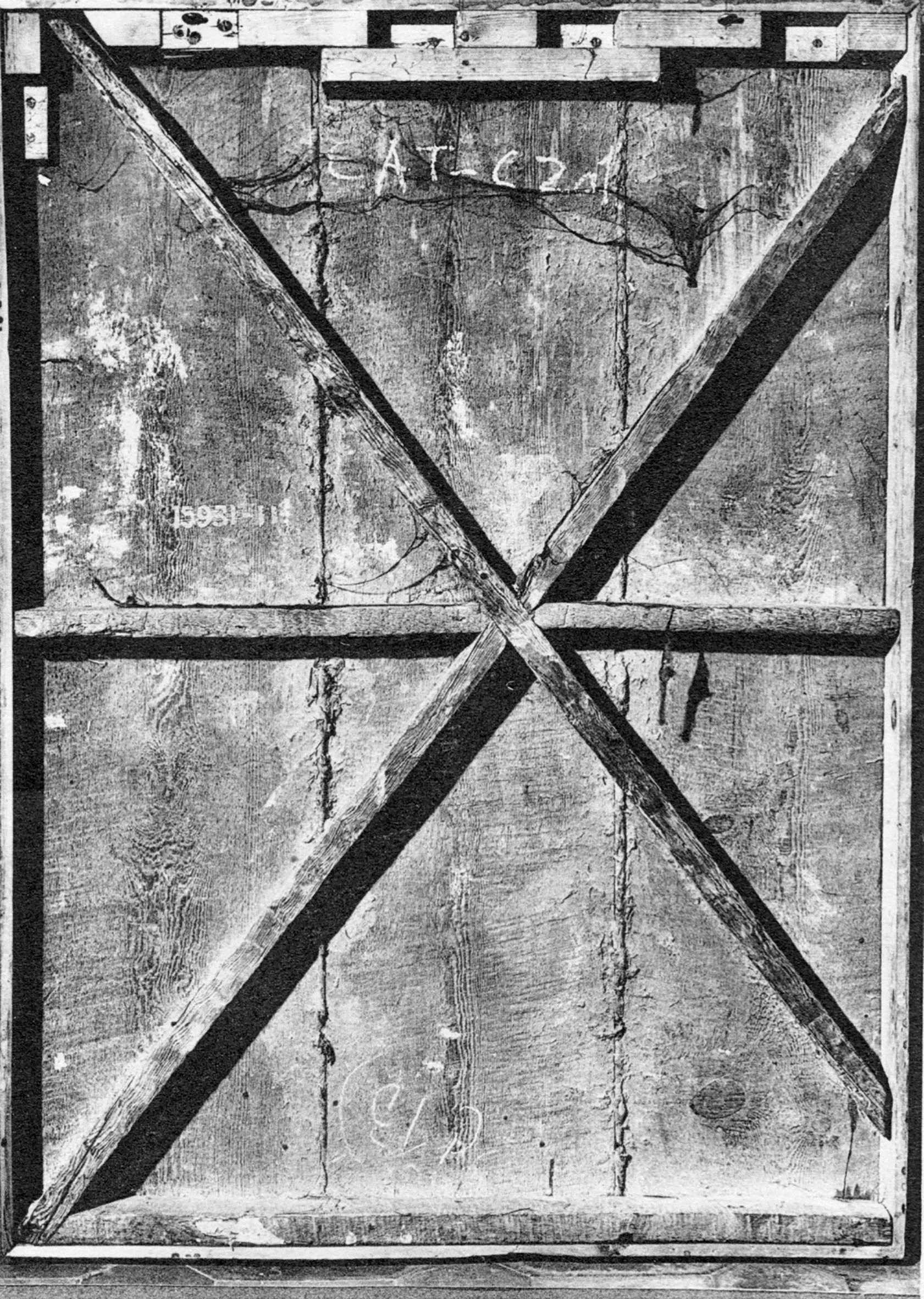

This method is common in Spain but appears to have been confined to that region: we did not find a single example anywhere else. It was nevertheless used by all the Spanish schools. We note those in particular from Catalonia, Valencia and Aragon, which we had more opportunity to study. With certain variations, all these schools had the idea from the 15th century onward of strengthening their wooden panels by adding primitive diagonal braces to rudimentary cross-bars.

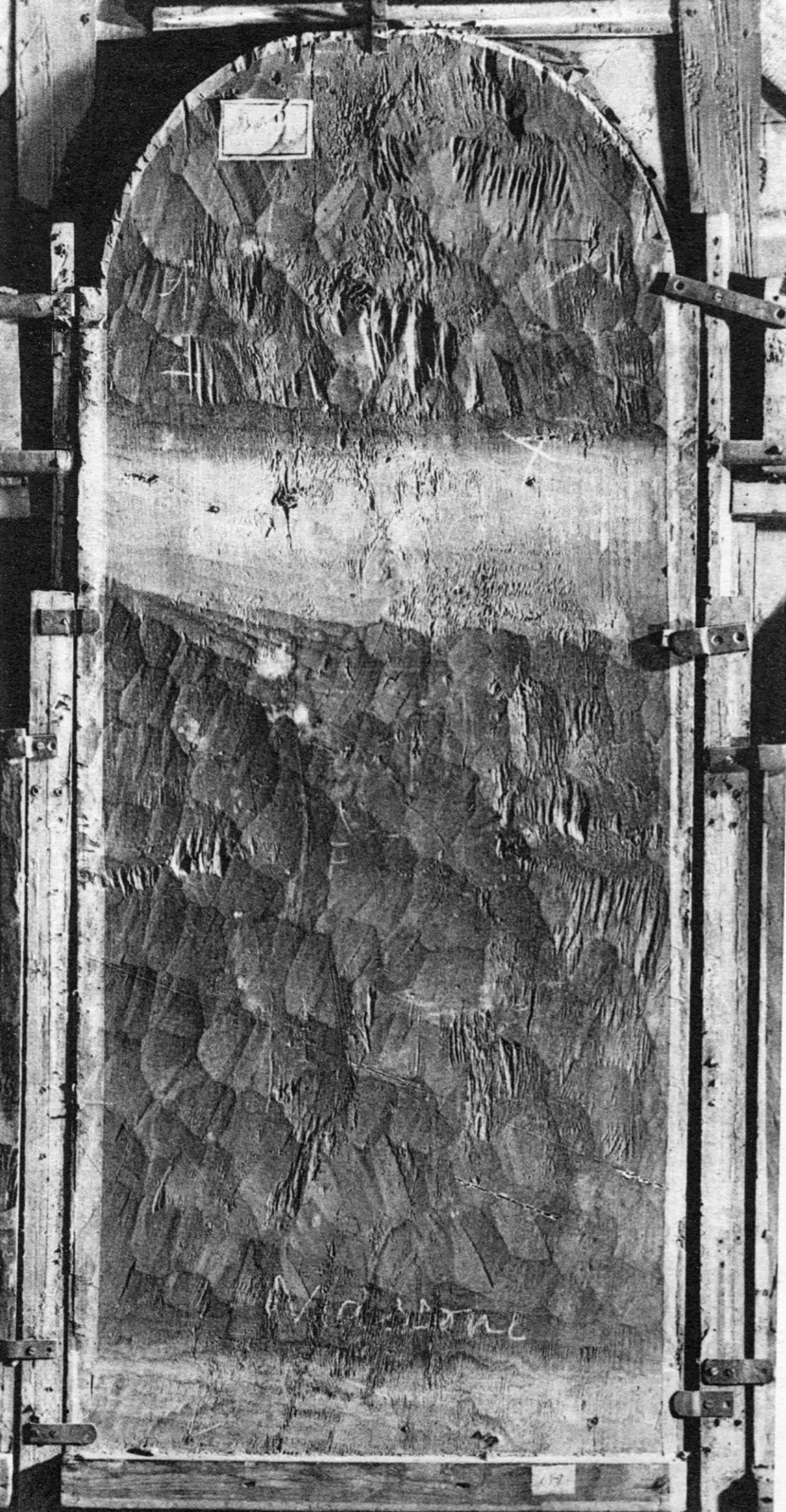

The use of simple cross-bars appears to be older than the combination of diagonal braces and horizontal members. Older Spanish panels – the 13th- and 14th-century antependia15Painting index, nos. 893 and 883. – are indeed fitted with simple cross-bars. It is only later, towards the end of the 14th century and beginning of the 15th, that diagonal braces first appear as reinforcements. The altarpiece panel painted in 1350 by the Master of San Vicente16Painting index, no. 441. is the earliest example of which we are aware (Fig. 104). The diagonal braces meet in the middle, linking the opposite corners of the panel. They generally abut the cross-bars at the top and bottom. One or more cross-bars sometimes reinforce the panel at the centre too.17Editors’ note: Example of transversal bars fixed on to the frame: A. Bouts, Triptych of the Assumption of the Virgin, Inv. no. 574, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique/Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België. In most cases there is only one (Figs 105 and 106). Variations on these arrangements exist: the outermost cross-bar may be absent and the braces may cross somewhere other than the middle of the panel.

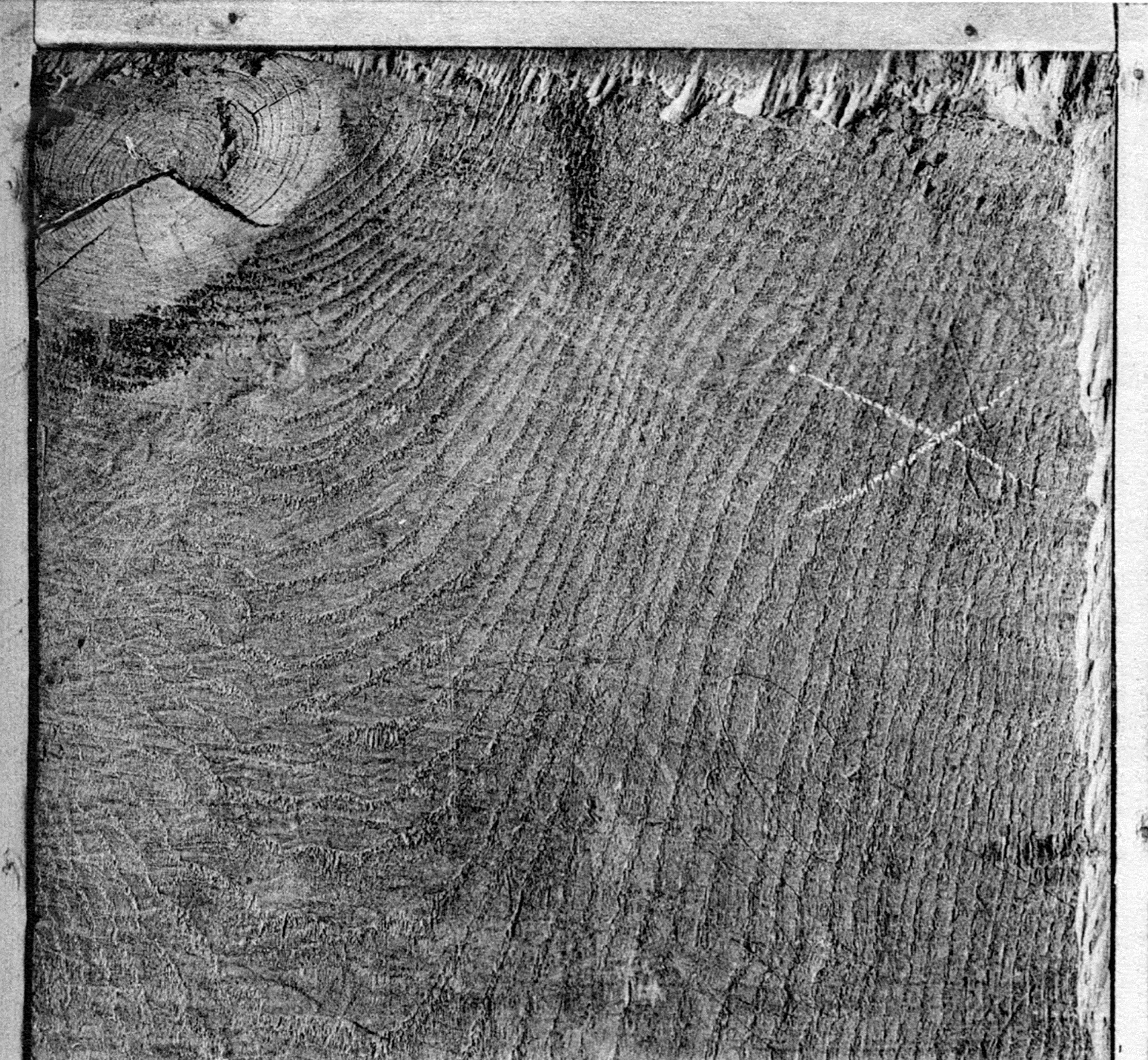

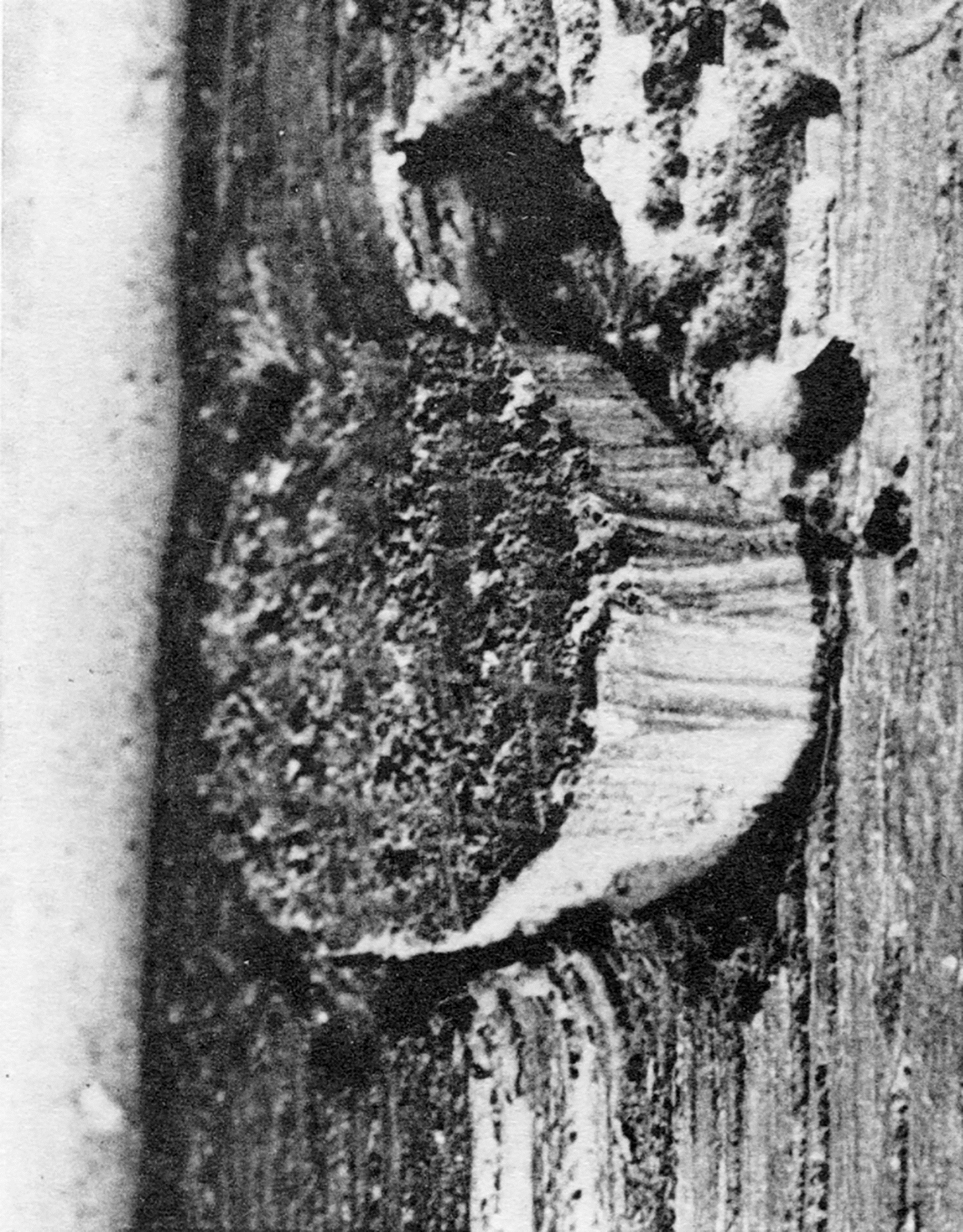

Figure 86 Tangential or plain-cut section: flaw in the wood. The knot in the left upper corner corresponding with a large branch cut off transversely. (Vasco Fernandez, St Peter Altarpiece. Viseu, Musée Grâo Vasco. Painting index, no. 10.)

Figure 87 Flaws in the wood: multiple knots. (Bréa workshop, late 15th century, St John the Baptist and St Bartholomew. Nice, Musée Masséna. Painting index, nos. 365 and 366.)

Figure 88 Large panel consisting of a single board. (Vasco Fernandez, Creation of the Animals. Lamego, Museum. Painting index, no. 312.)

Figure 89 Scarf-joined boards. (Portuguese School, early 16th century, The Resurrection. Tomar, Convent of Christ. Painting index, no. 254.)

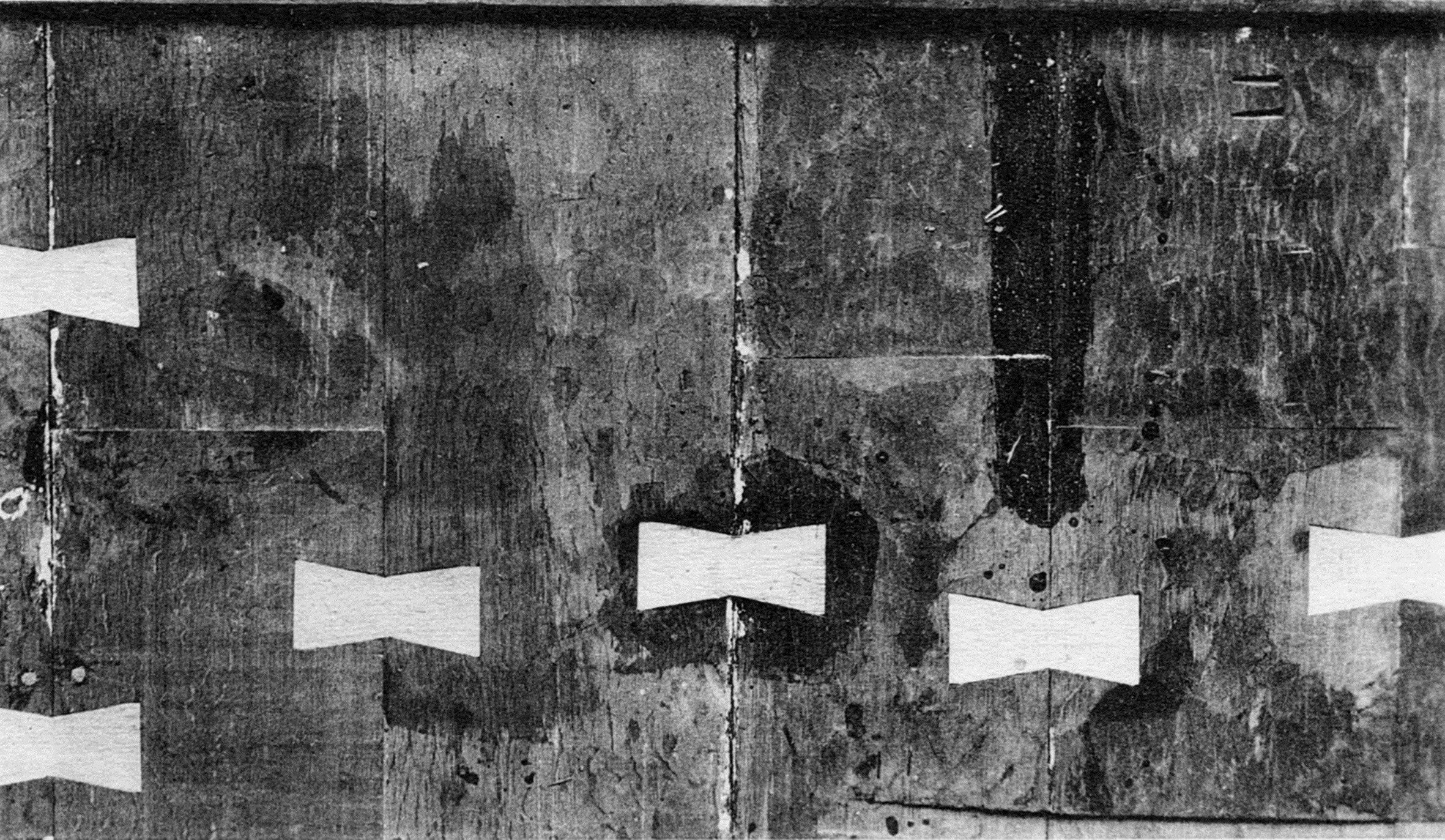

Figure 90 Boards joined with double dovetails on the front. (Aragonese School, 16th century, The Adoration of the Magi. Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, no. 438.)

Figure 91 Boards joined with butt joins on the back. (Aragonese School, 16th century, The Adoration of the Magi. Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, no. 438.)

Figure 92 Boards joined with a single dovetail on the front, visible on the joint at the centre of the image. (Jacopo di Cione, The Coronation of the Virgin with Adoring Saints. Florence, Galleria dell’Accademia. Painting index, no. 573.)

Figure 93 Boards joined with butt joins on the back. (Jacopo di Cione, The Coronation of the Virgin with Adoring Saints. Florence, Galleria dell’Accademia. Painting index, no. 573.)

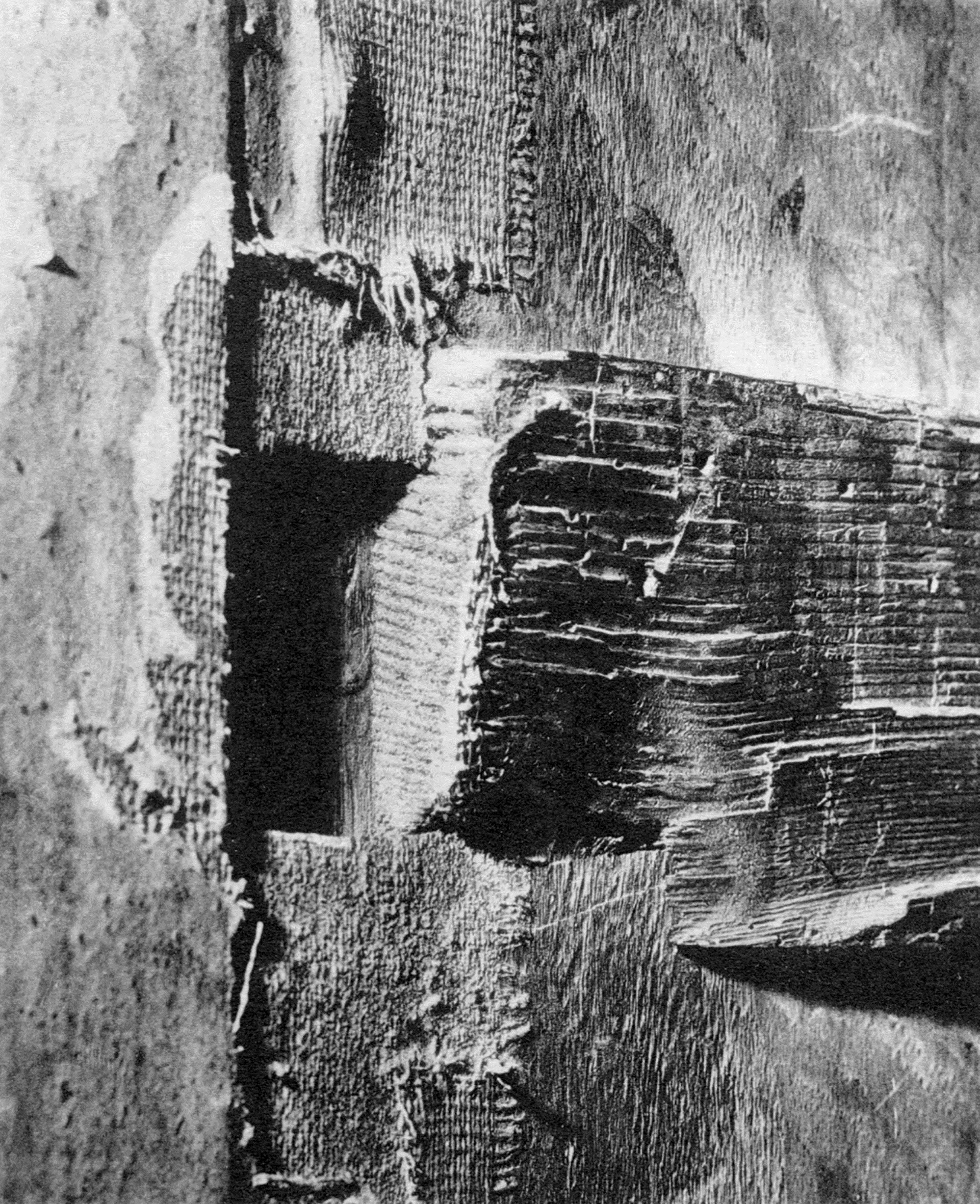

Figure 94 Boards joined with a halved cross-lap join, deep shouldering. (Lluís Dalmau, Virgin of the Consellers. Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, no. 61.)

Figure 95 Boards joined with a halved cross-lap join, shallower shouldering. (Castilian School, ca. 1320, Funeral Processions. – Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, nos. 384, 387 and 389.)

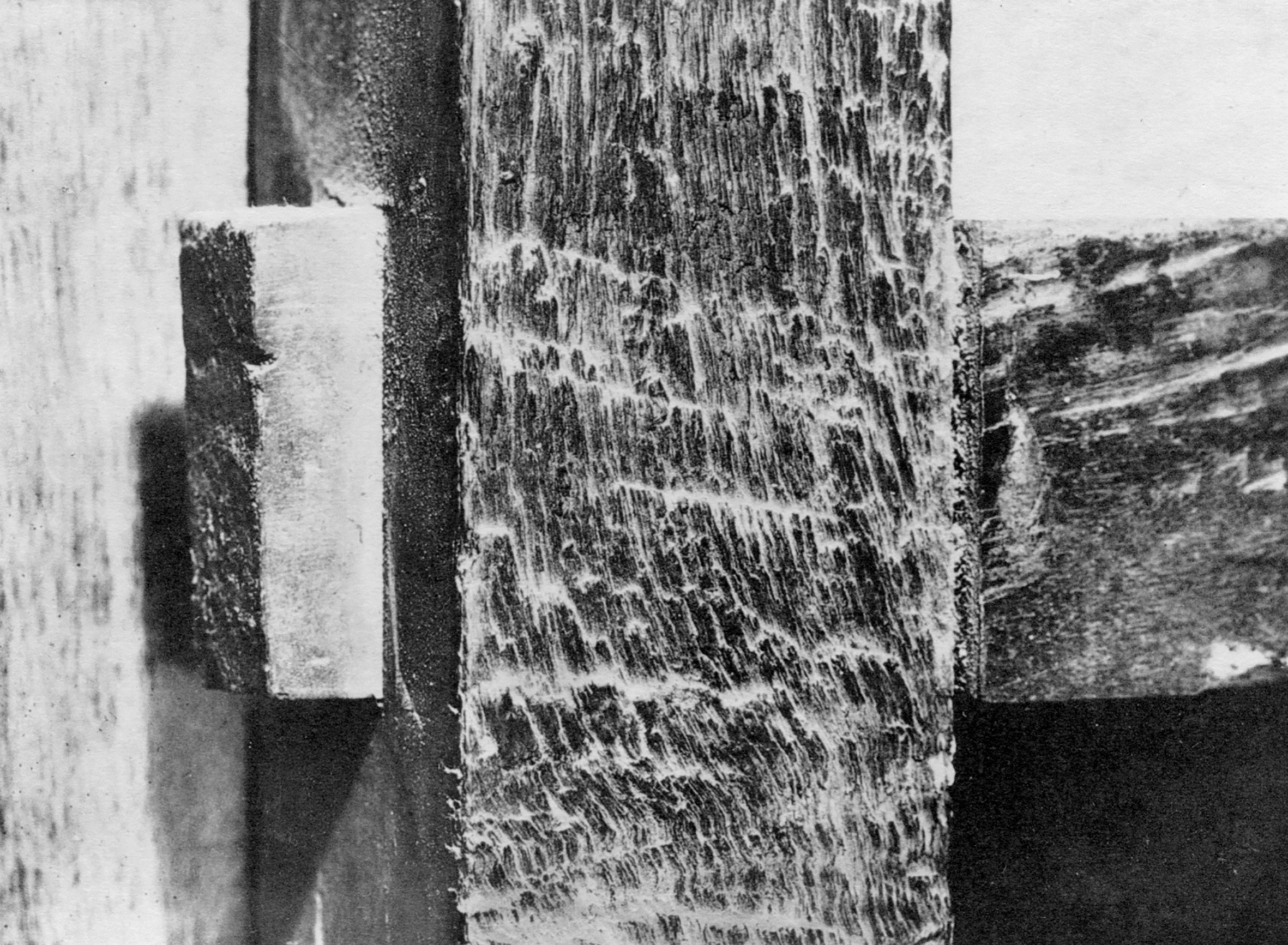

Figure 96 Boards joined with butt joins and filler. (Aragonese School, 14th century, St Ursula Altarpiece, detail, see Fig. 112. Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, no. 883.)

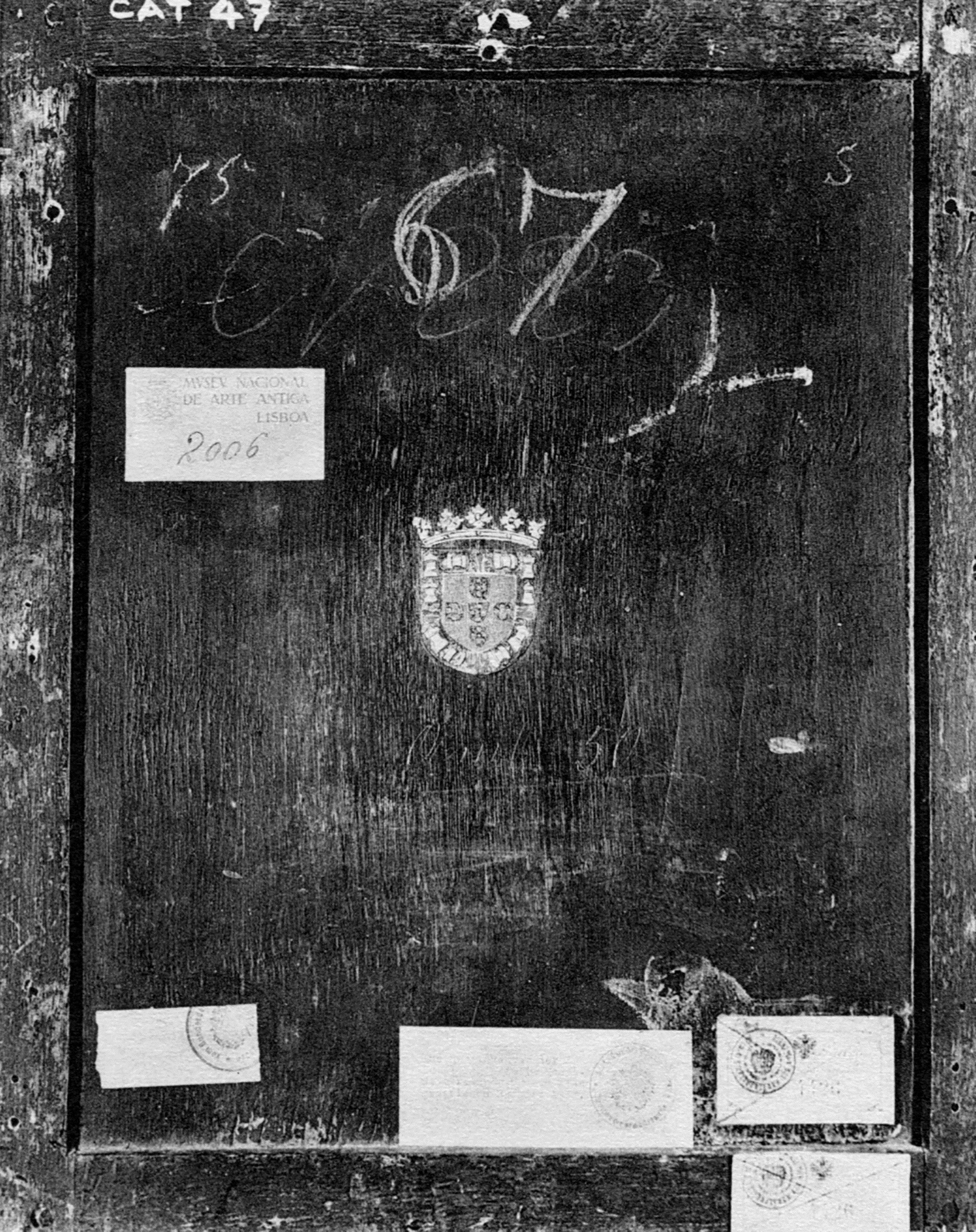

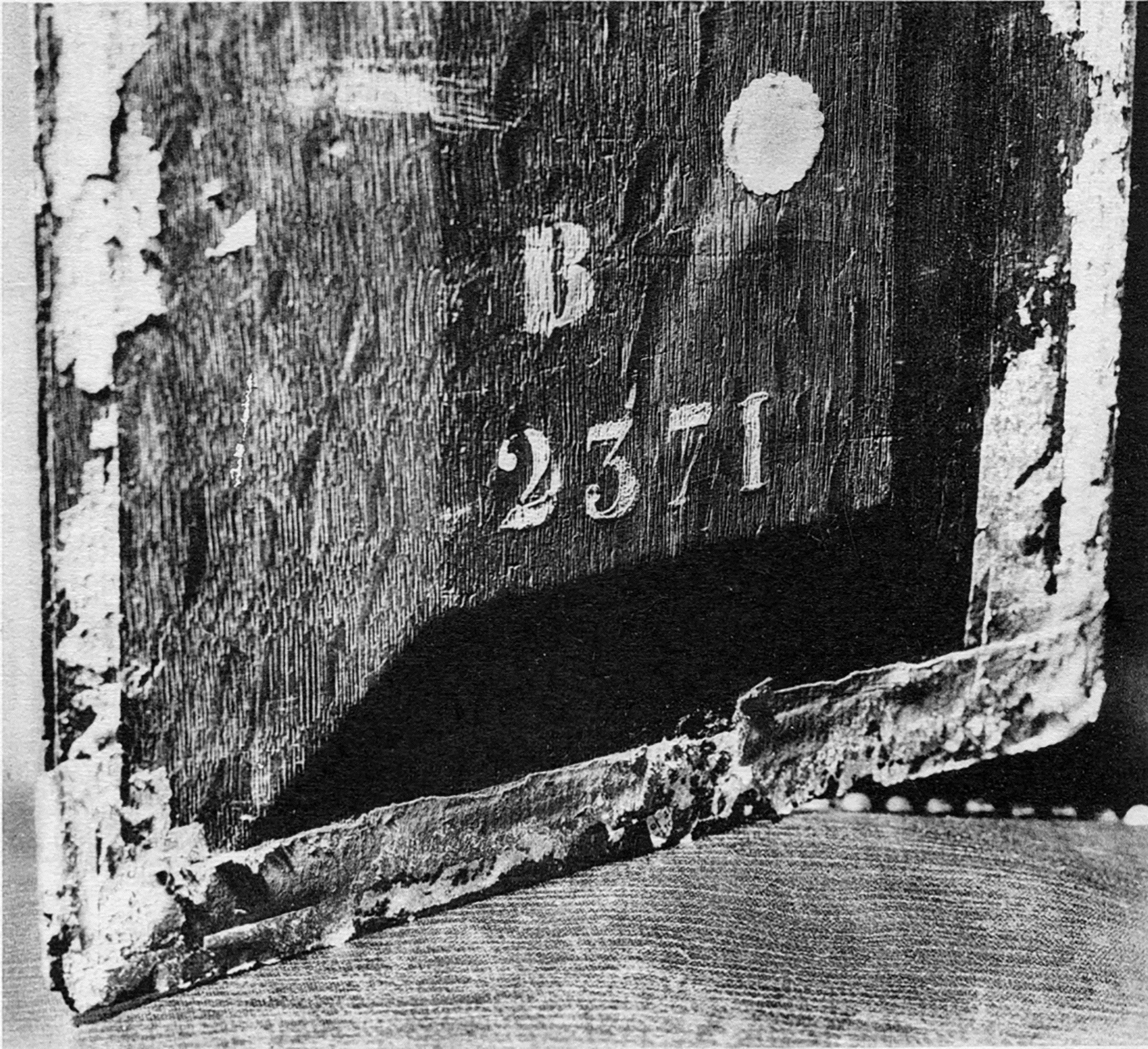

Figure 97 Dowel seen from the edge of the panel. (Nuno Gonçalves, St Vincent Polyptych: Three Benedictine Monks from Alcobaça. Lisbon, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga. Painting index, no. 298.)

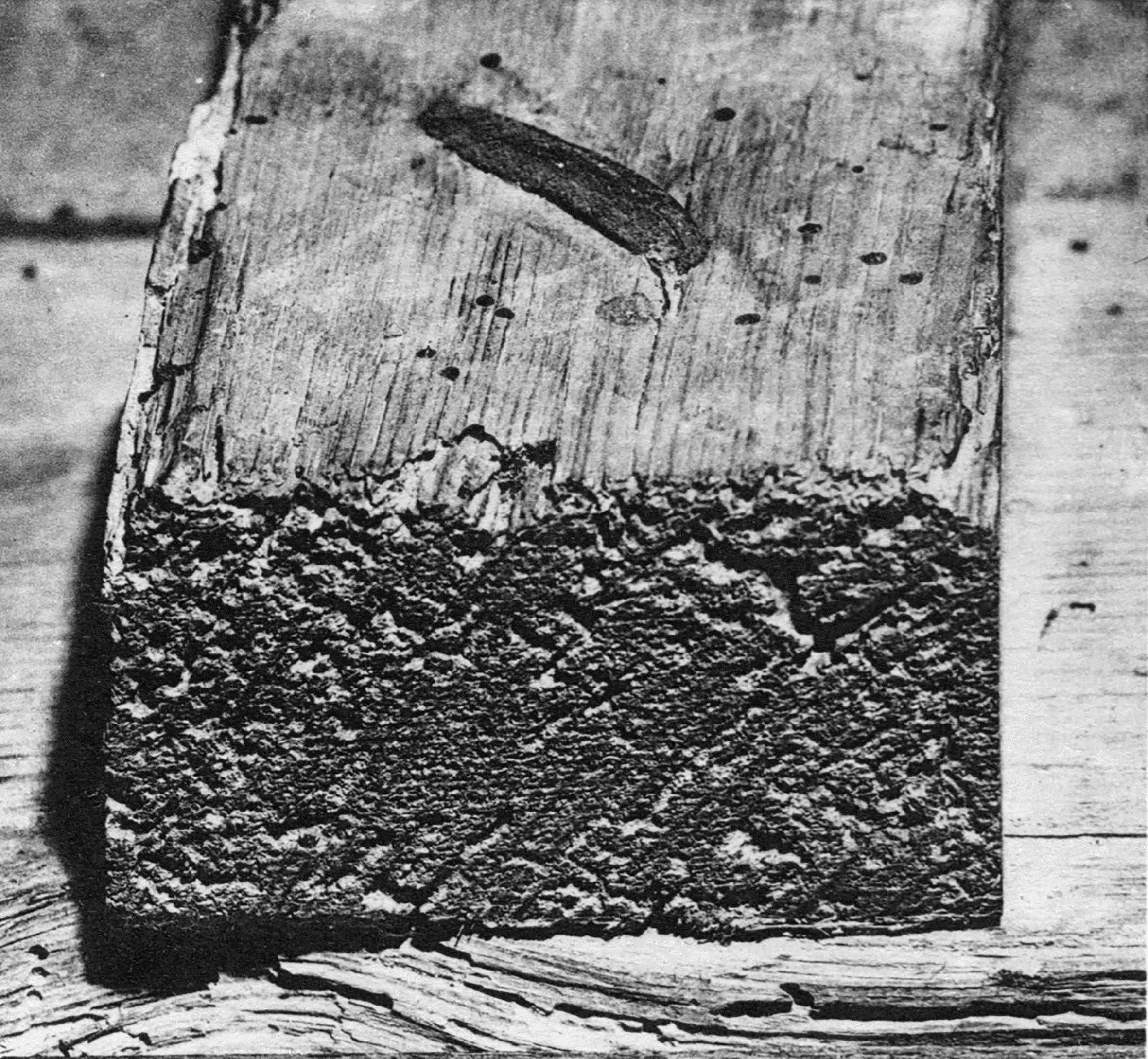

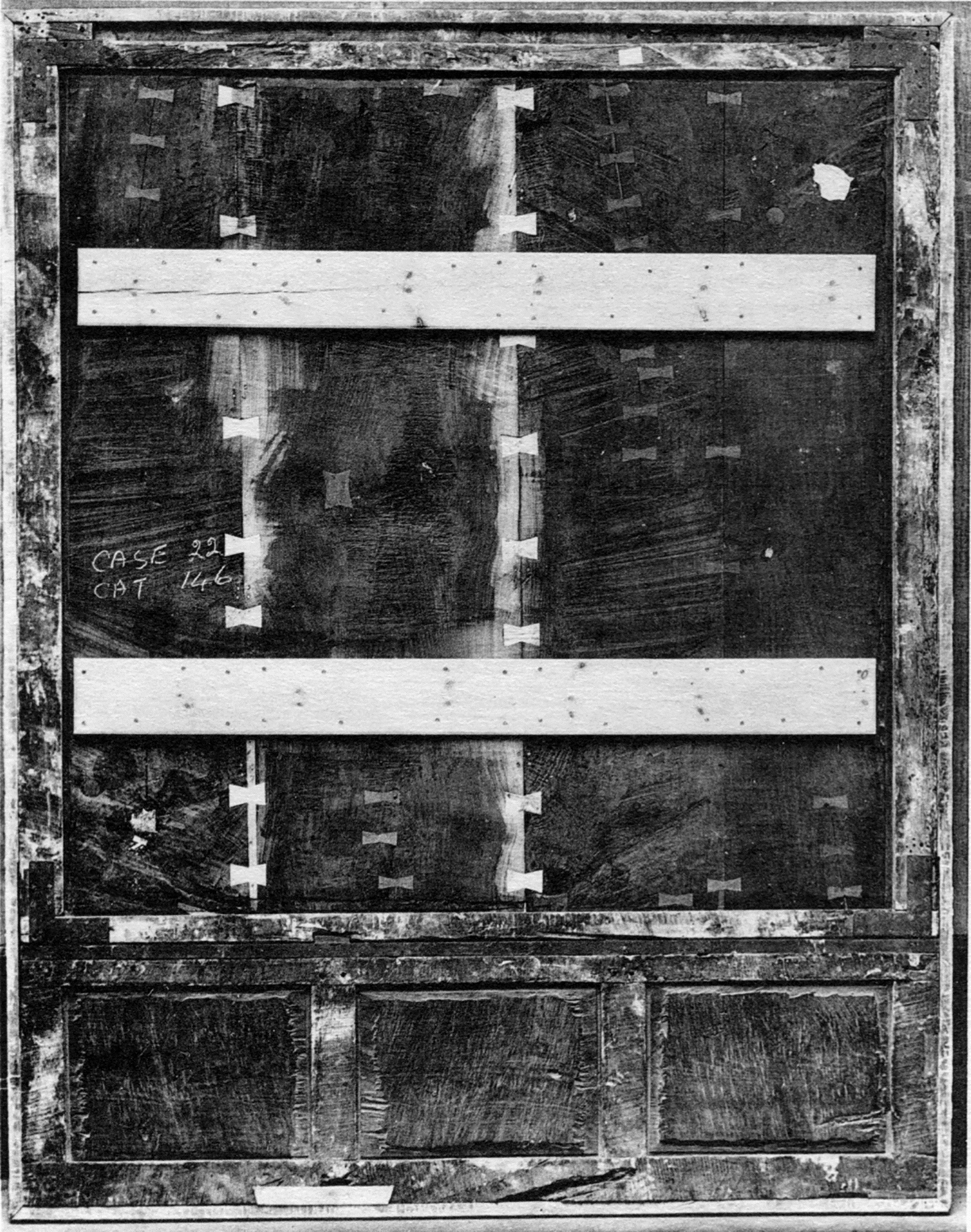

Figure 98 Dowels on the back of a split panel. (Nuno Goncalves, St Vincent Polyptych: Three Fishermen with their Net. Lisbon, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga. Painting index, no. 299.)

Figure 99 Overview of a split panel assembled using dowels. (Duccio, Maestà. Siena, Opera del Duomo. Van Marle 1924–1928, II: 20–60.)

Figure 100 Trace of a surface-mounted cross-bar with slight preparation of the support. (Giovanni Massone, Triptych. Paris, Musée du Louvre. Painting index, nos. 651–653.)

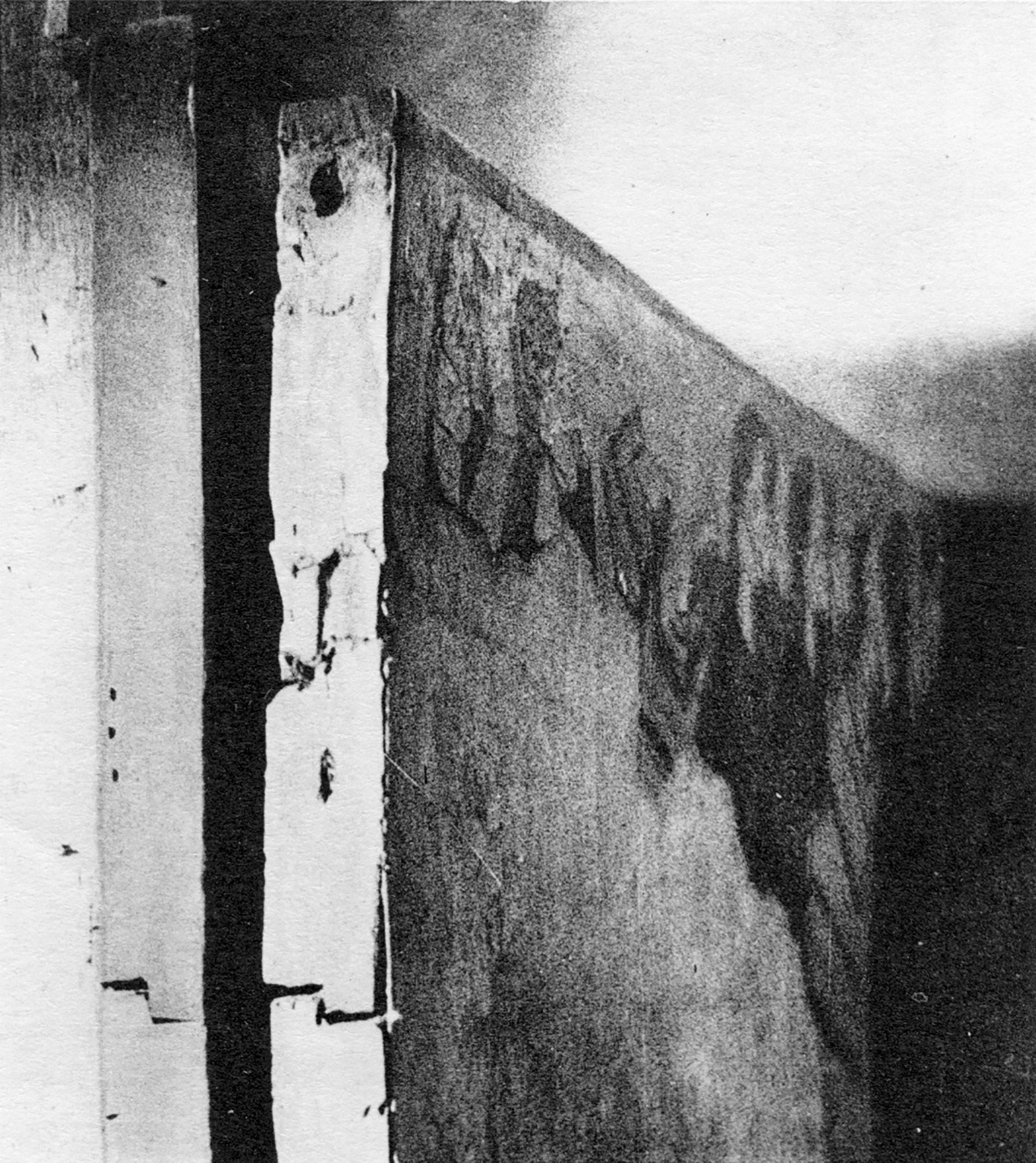

Figure 101 Cross-bars fixed to the support by clinched nails driven through the front. Nail heads are visible beneath the paint layer. (Giovanni Massone, Triptych. Detail. Paris, Musée du Louvre. Painting index, nos. 651–653.)

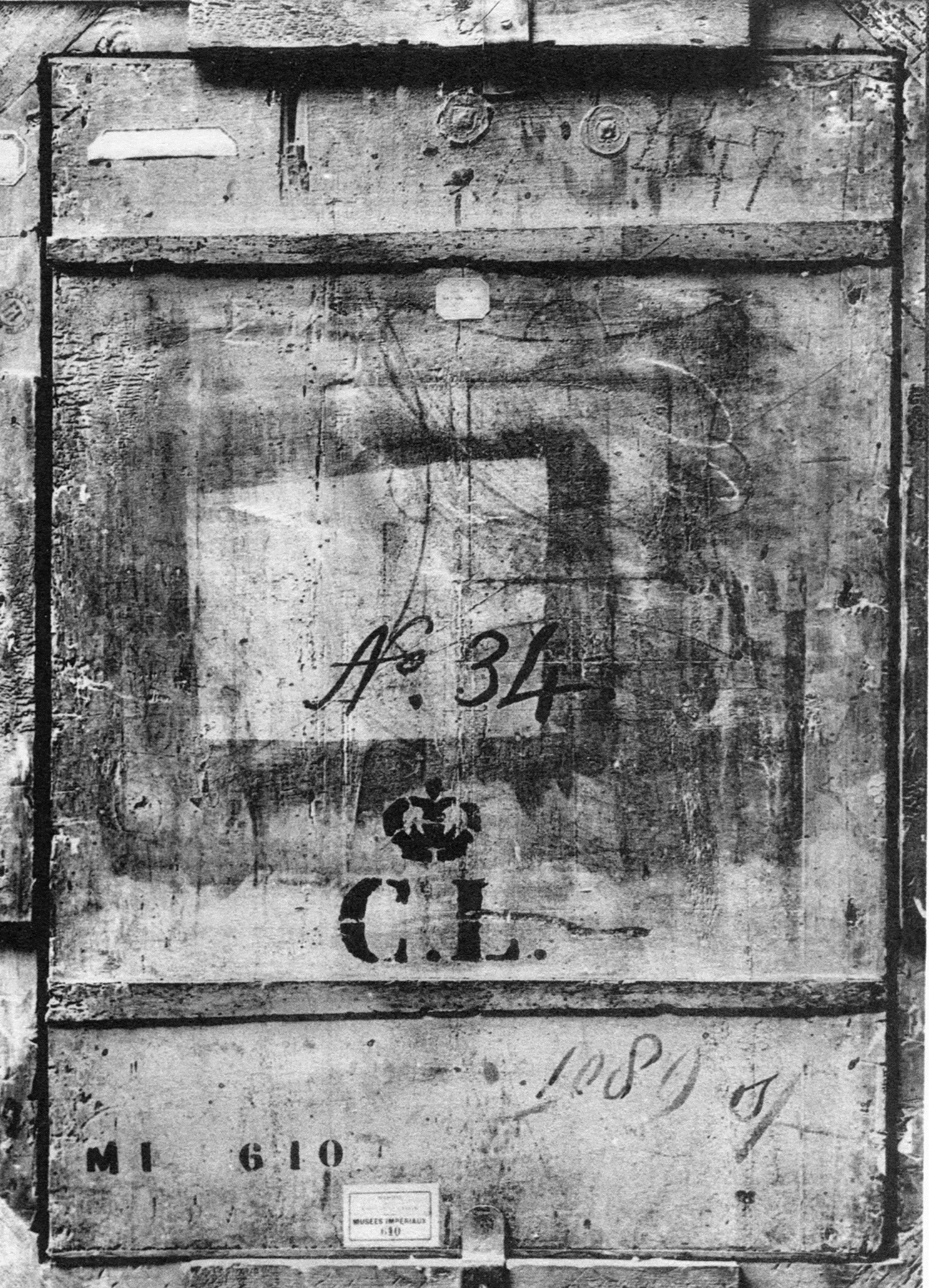

Figure 103 Tapering cross-bars mounted head to toe. (Paolo Zacchia il Vecchio, Portrait of a Musician. Paris, Musée du Louvre. Painting index, no. 529.)

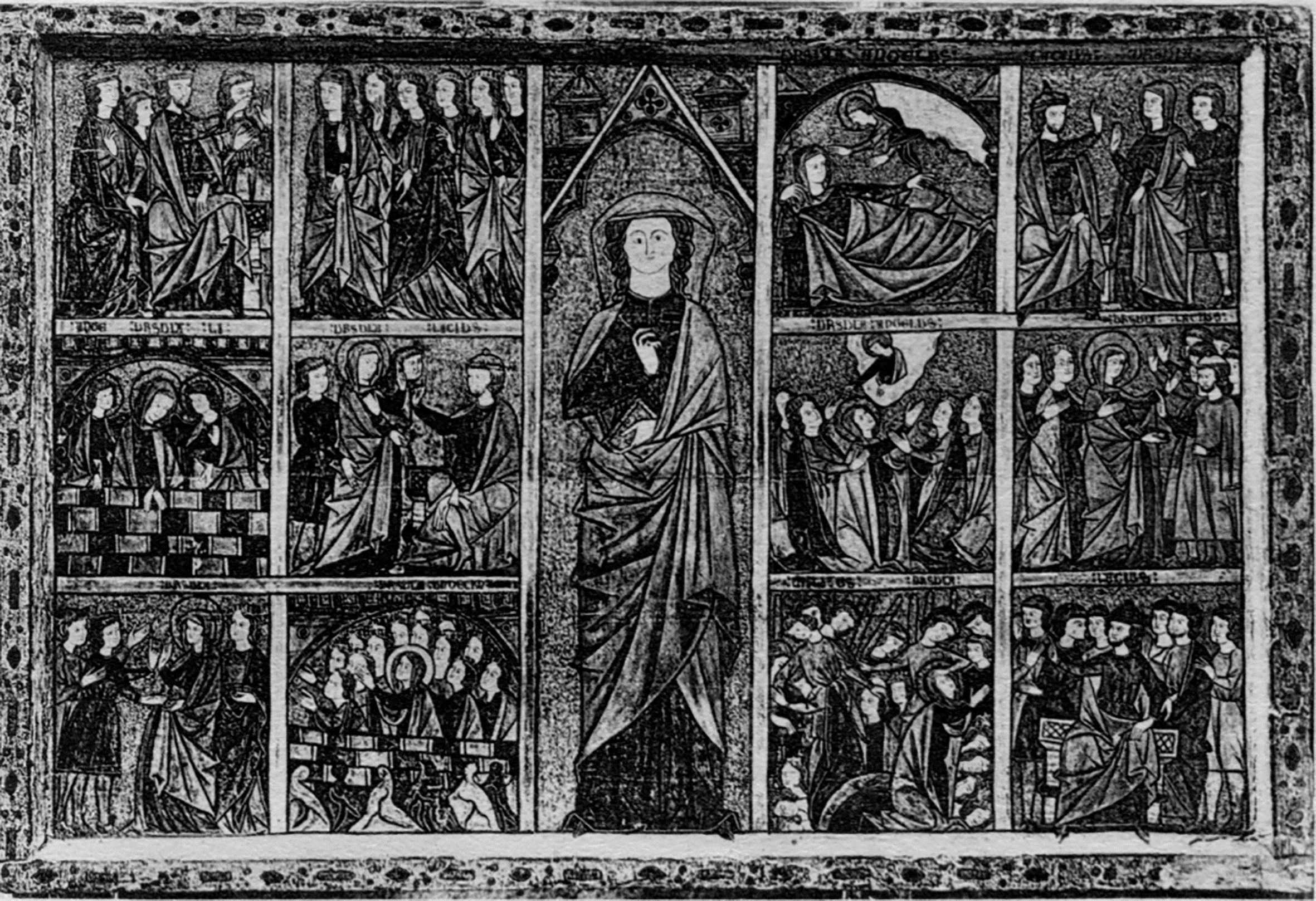

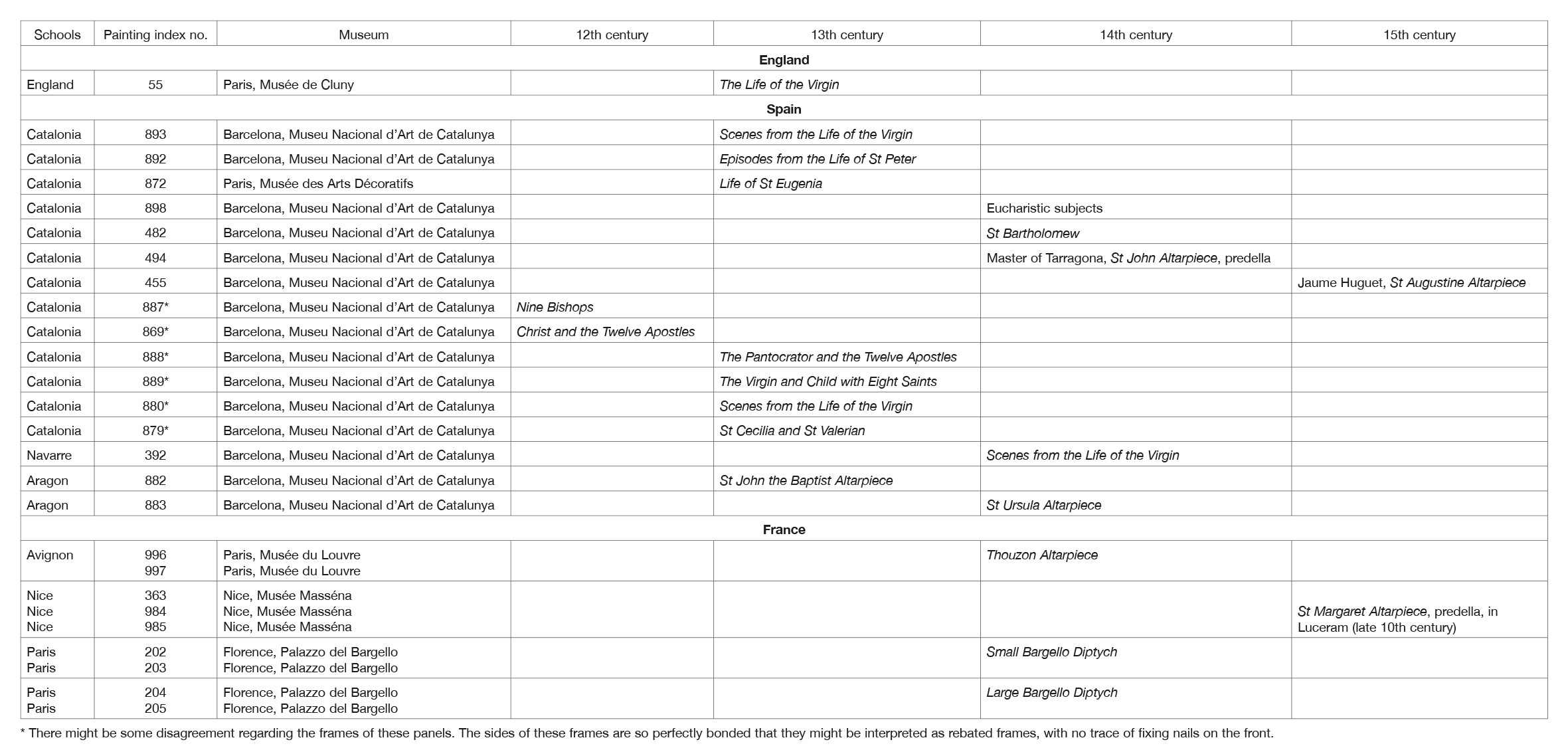

Figure 104 Master of San Vicenç dels Horts, St Vincent. (Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, no. 441.)

Figure 105 Master of Játiva, Scenes from the Life of the Virgin and of Christ: The Annunciation. (Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, no. 914.)

Figure 106 Aragonese School, 15th century, The Coronation of the Virgin. (Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, no. 861.)

Figure 107 Rodrigo de Osona the Younger, The Virgin and Child. (Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, no. 922.)

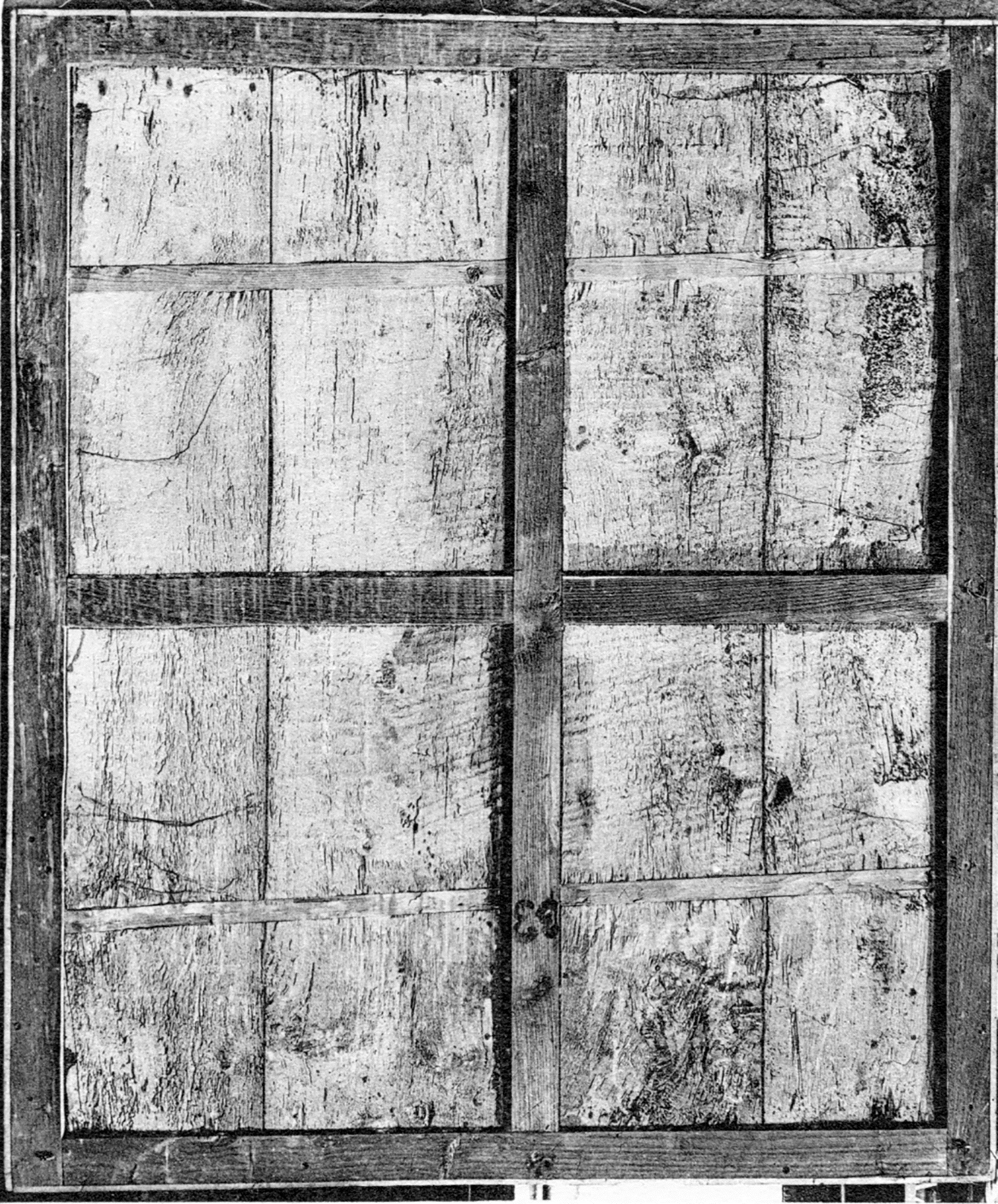

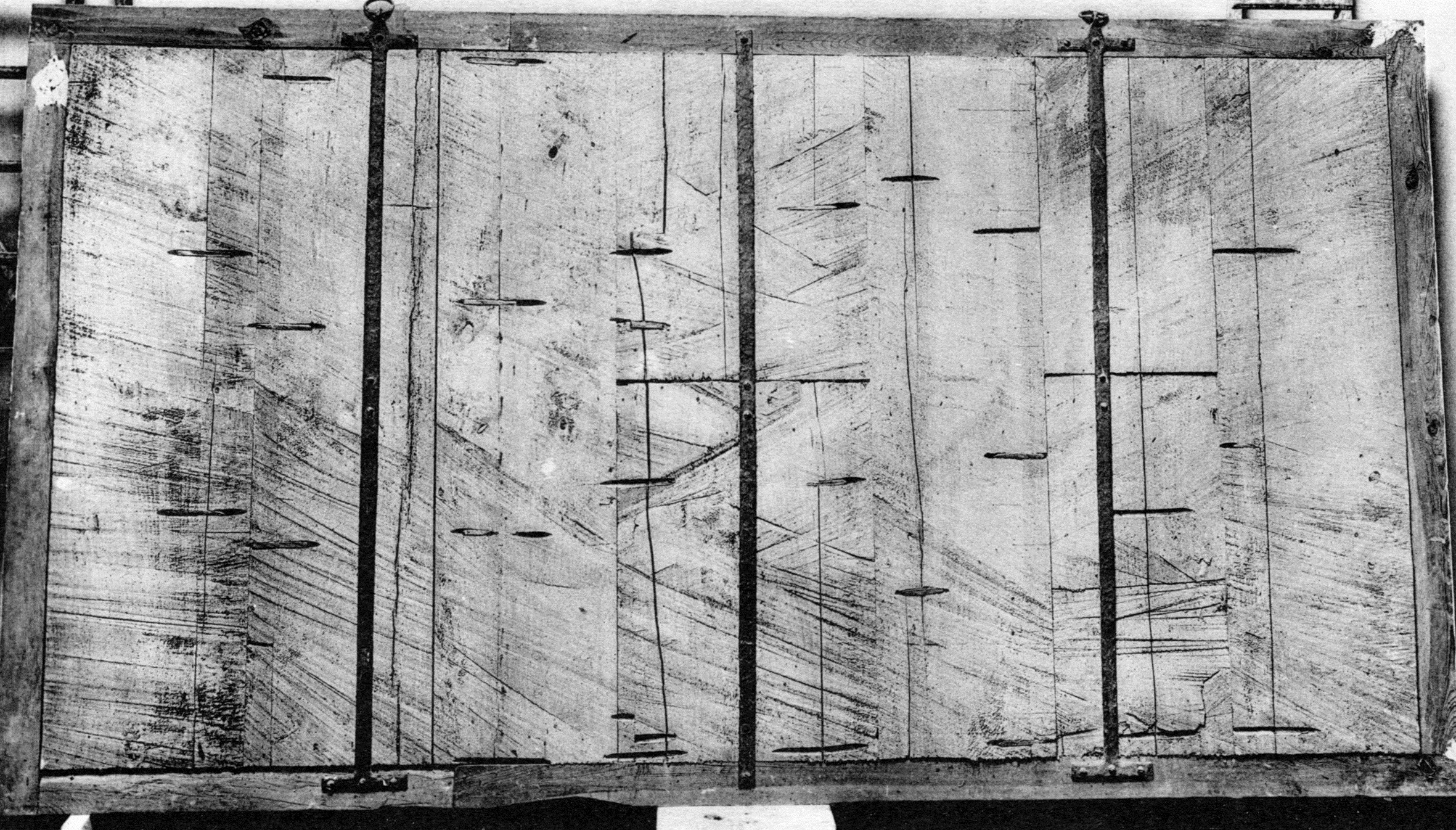

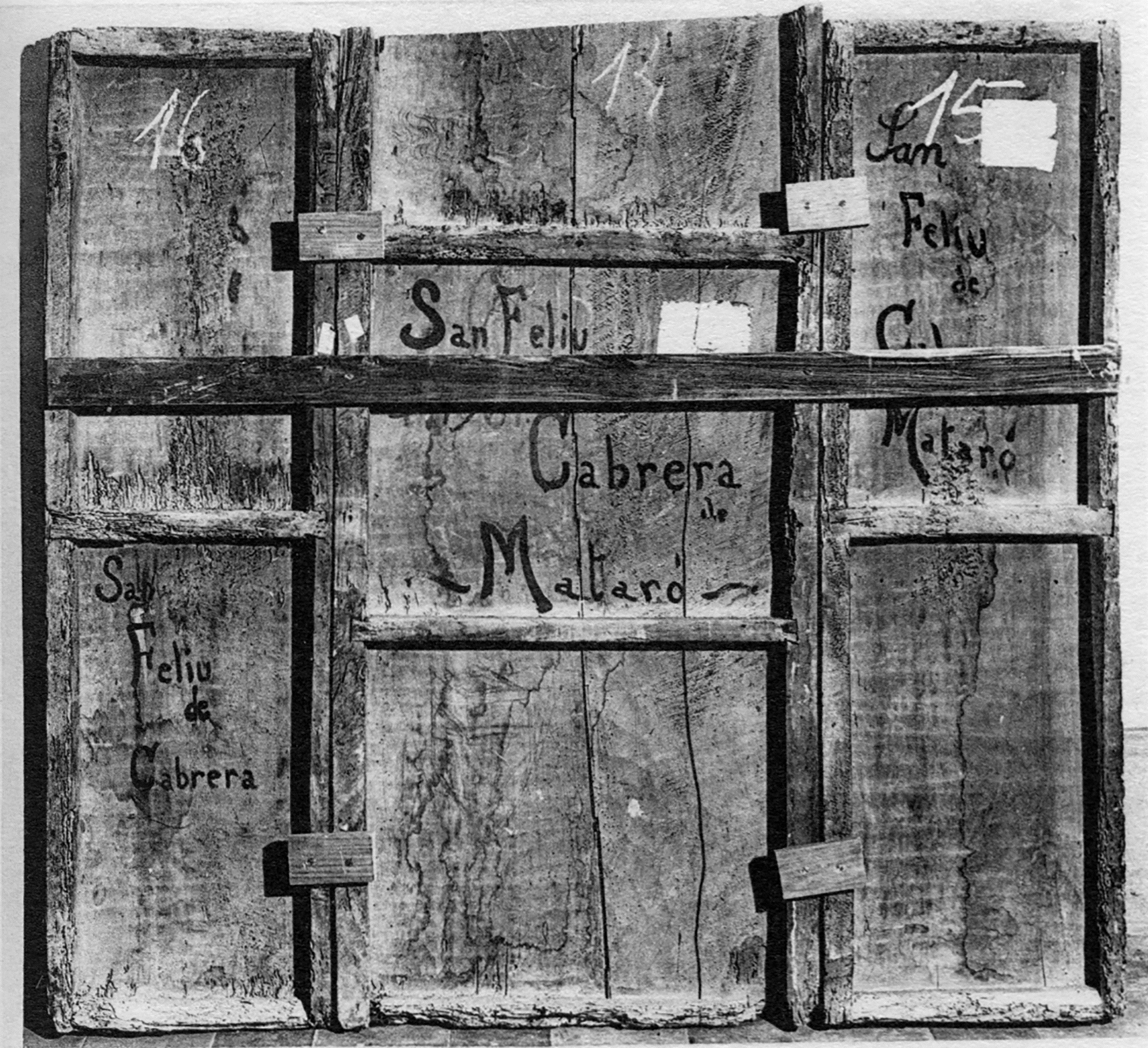

Figure 108 Reinforcing frame with one or two central cross-bars. (Bernat Martorell, St John the Baptist Altarpiece. Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, nos. 456, 457 and 458.)

Figure 109 Diagonal braces and outer cross-bars. (Jean Gascó, St Sebastian and St Martial, Bishop. Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, no. 488.)

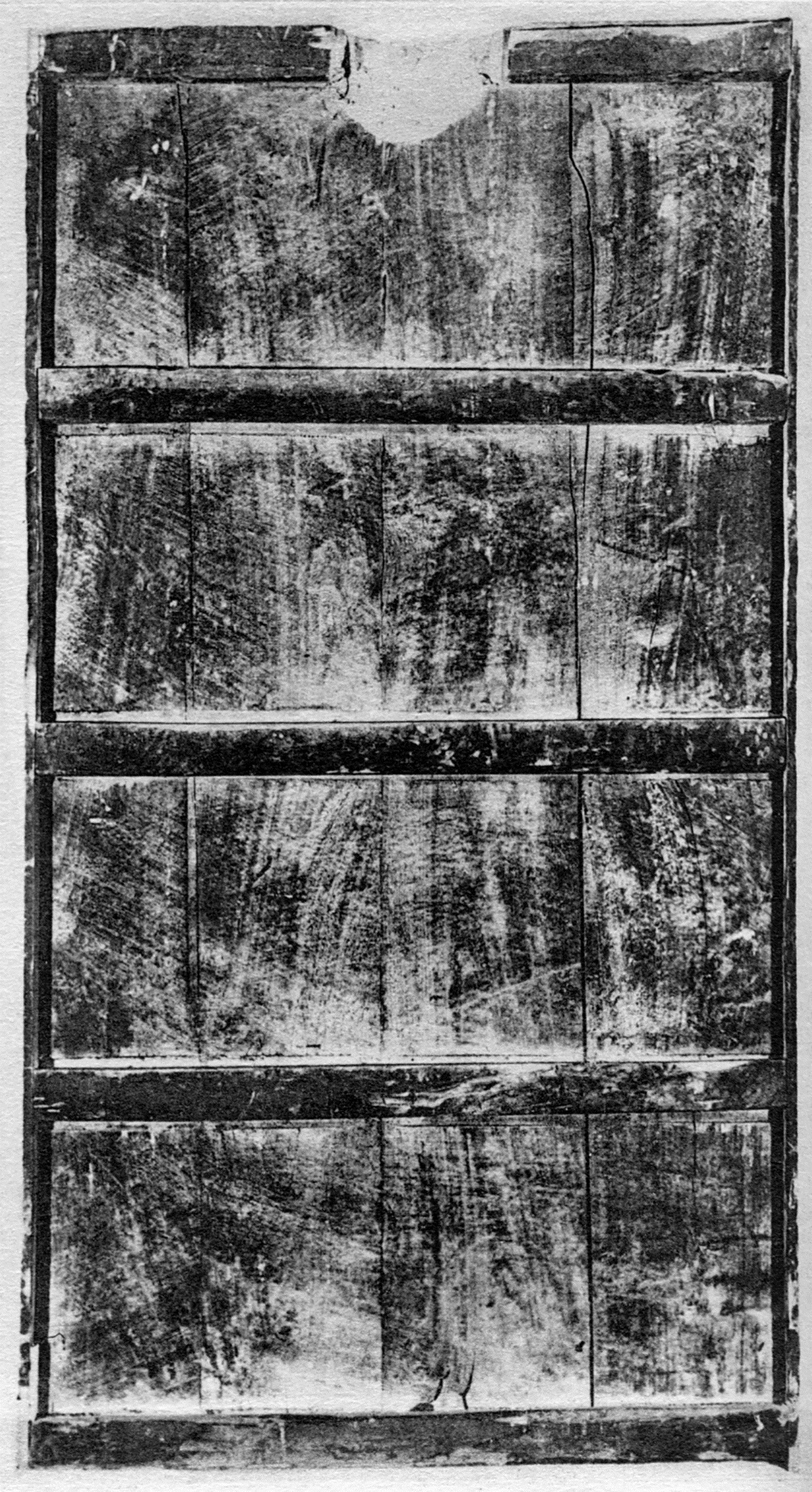

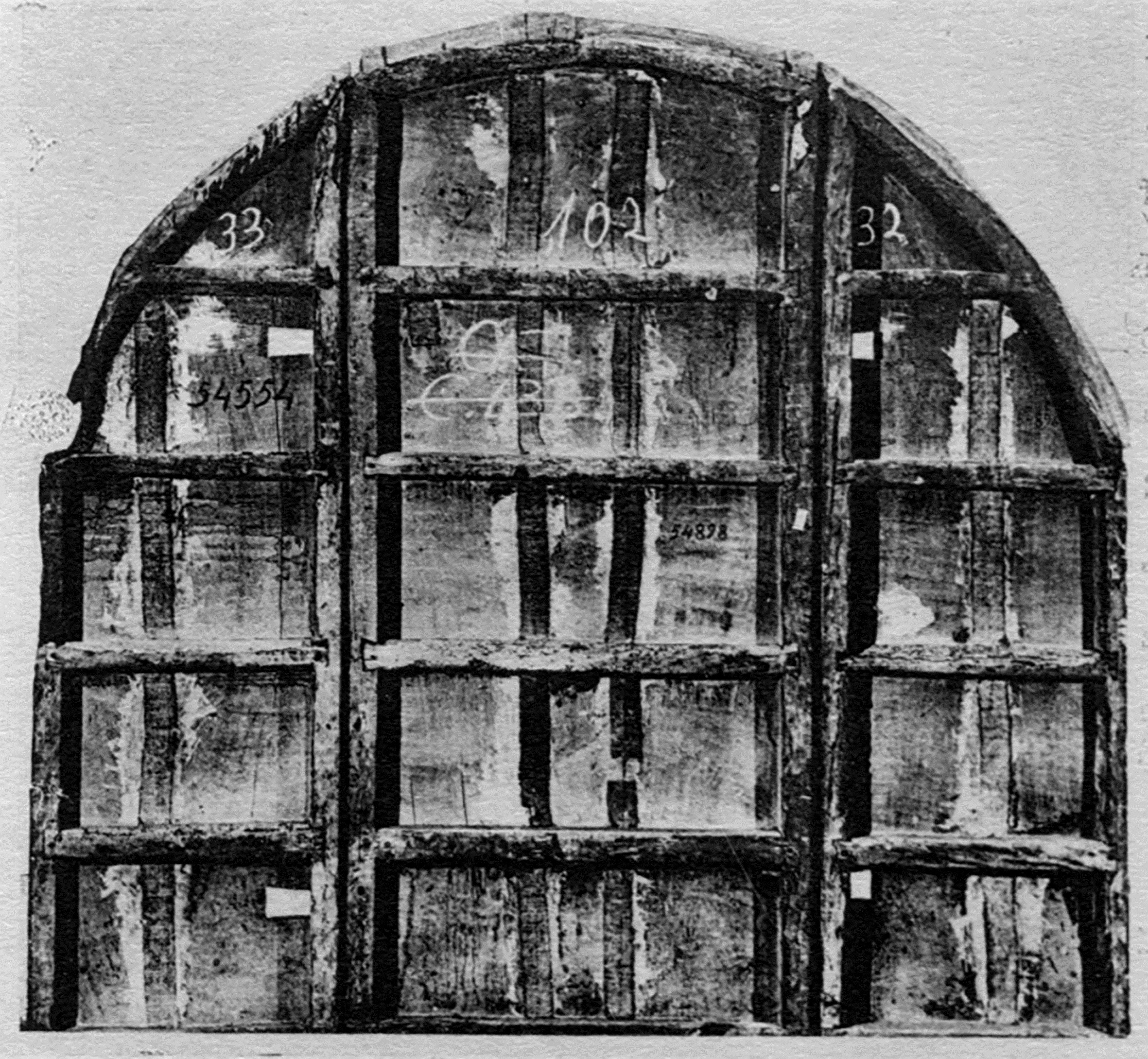

Figure 110 Reinforcing frame with four central cross-bars. (Pere Garcia de Benabarre. St Quiricus and St Julietta Altarpiece. Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, nos. 445, 446 and 447.)

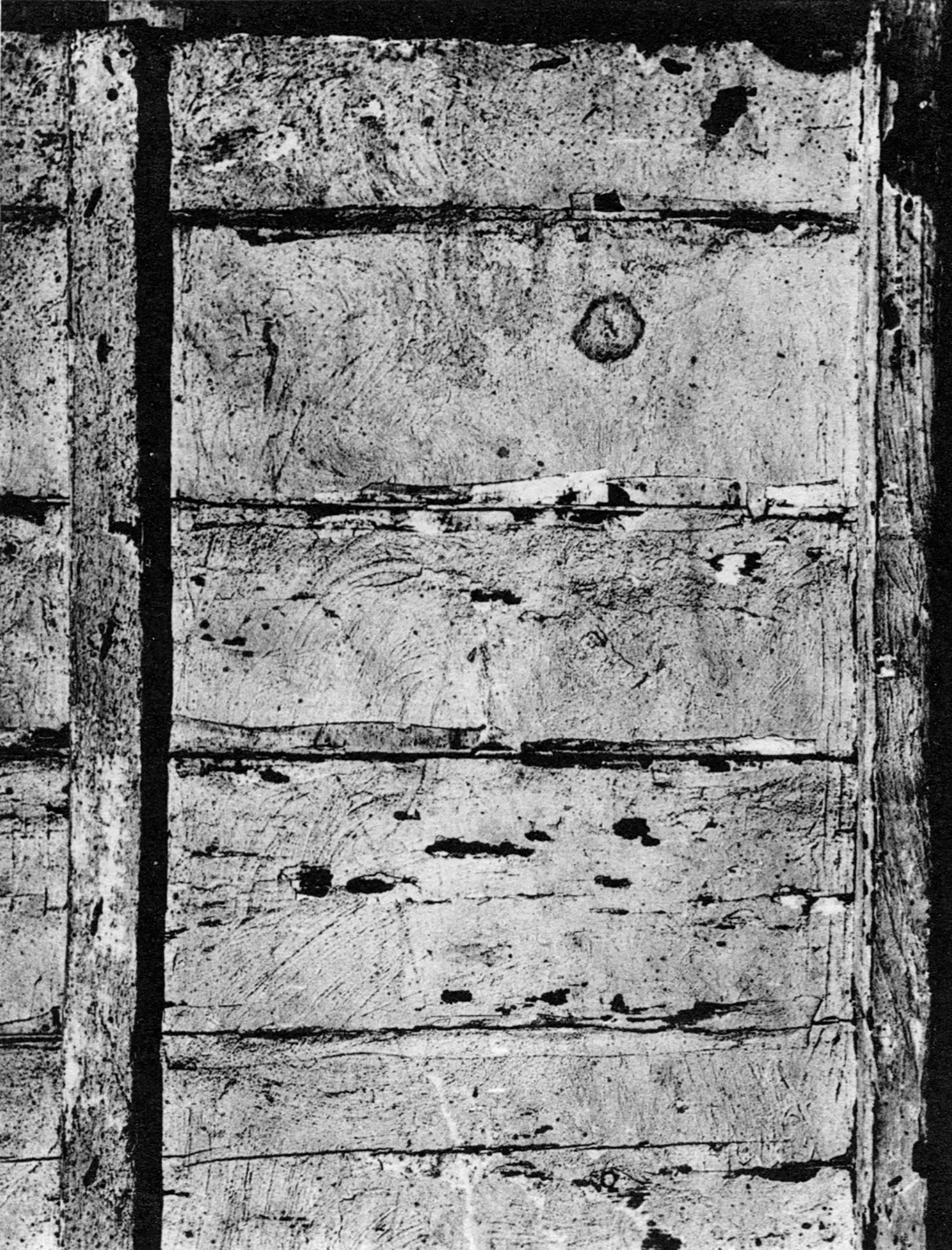

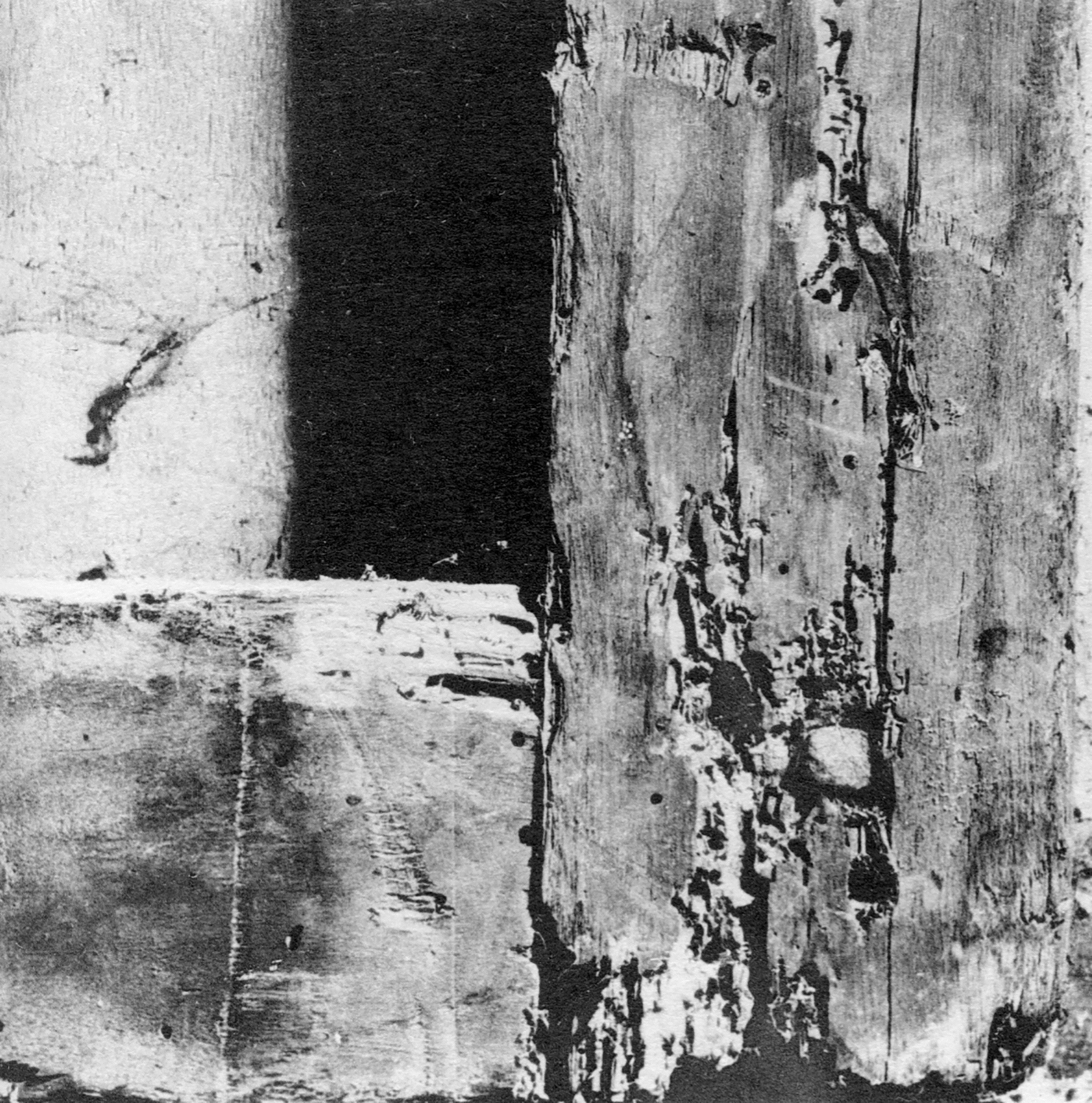

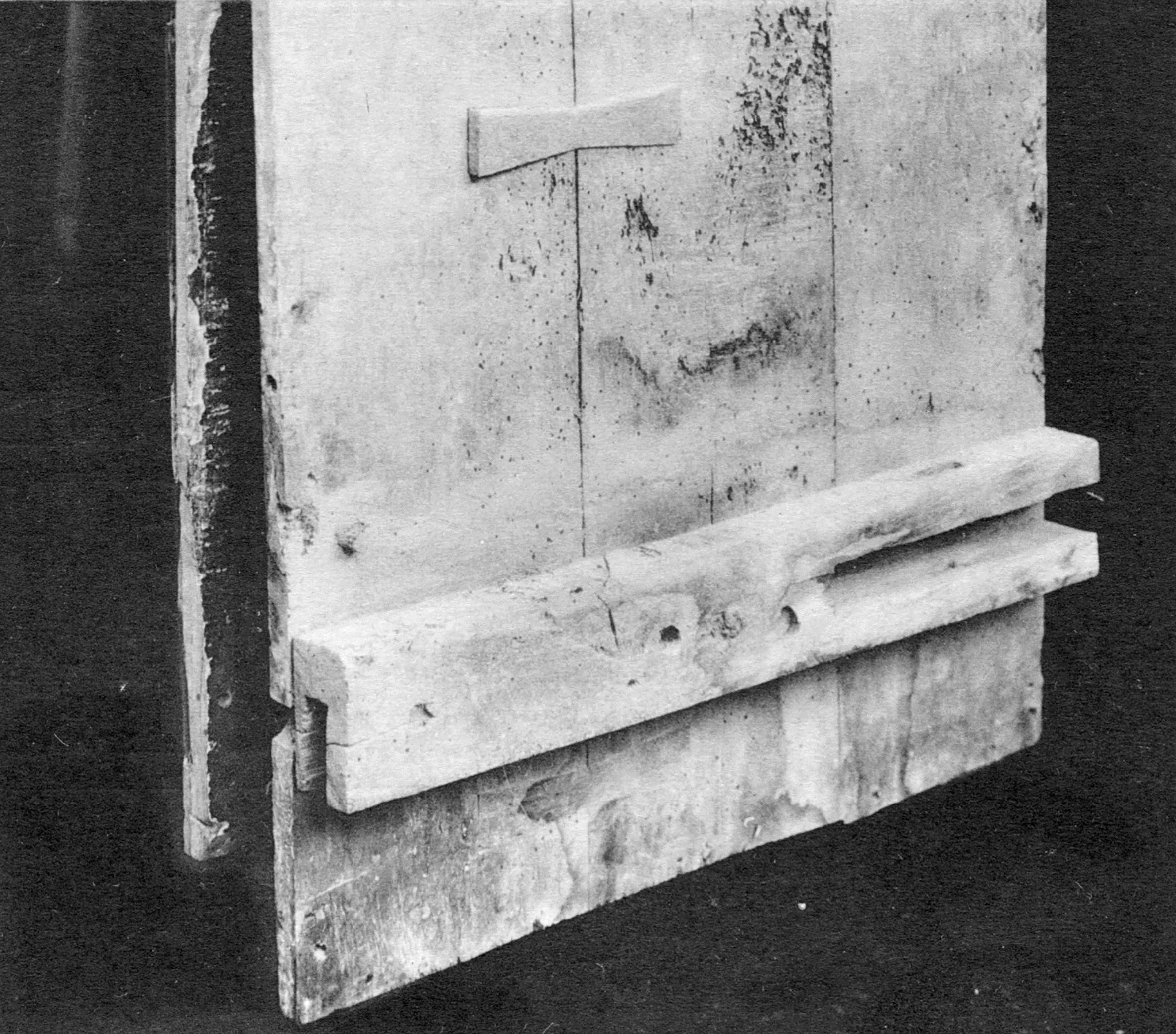

Figure 111 Frame mounted on the front. (Aragonese School, 14th century, St Ursula Altarpiece. Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, no. 883.)

Figure 112 Frame reinforced on the back by uprights on the sides. (Aragonese School, 14th century, St Ursula Altarpiece. Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, no. 883.)

Figure 113 Rebated frame. (Catalan School, 13th century, The Pantocrator and Four Saints. Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, no. 870.)

Figure 114 Rebated frame. (Portuguese School, 15th century, Portrait of King John I. Lisbon, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga. Painting index, no. 244.)

Figure 115 Roughly bevelled edges. (Vasco Fernandez, Calvary Altarpiece. Viseu, Musée Grâo Vasco. Painting index, nos. 4–7.)

Figure 116 Regularly bevelled edges. (School of François Clouet, Elisabeth of Austria. Paris, Musée du Louvre. Painting index, no. 138.)

The thickness of the braces and cross-bars varies from thin (Fig. 105) to thick (Fig. 106). There are also examples of very wide cross-bars and very narrow braces in the same panel (Fig. 107). Other variations also no doubt exist within the different Spanish schools. We refer here solely to panels that we have had the opportunity to study in person. Several works from the Valencian School are also worthy of mention: the Master of Játiva’s panels for the altarpiece with Scenes from the Life of the Virgin and of Christ, painted in the second half of the 15th century;18Barcelona (Painting index, nos. 913–919). and the Adoration of the Magi by Joan Reixach, painted around 1460.19Barcelona (Painting index, nos. 923–924). For the 15th-century Catalan School, there is the fragment of the altarpiece in the Musée des Arts décoratifs in Paris, painted by the workshop of the Jaume brothers (died after 1405) and Pere Serra (active 1357–1406).20The Adoration of the Magi, The Resurrection and The Nativity (Painting index, no. 459).

All these panels belong to the 15th century, but the procedure seems to have remained in use after that. In the first quarter of the 16th century Joan Gascó (ca. 1500–1529) painted his St Sebastian and St Martial, Bishop21Barcelona (Painting index, no. 488). on a panel reinforced in the same way (Fig. 109). The central cross-bars have disappeared in this case, however, and the technique for cutting the wood has improved. The rudimentary system of simple cross-bars attached via the front of the panel persisted in this period, as we see in Joan Gascó’s Scene of Invalids at the Tomb of a Saint22Barcelona (Painting index, no. 383). and the series of panels attributed to the same artist that make up the St Stephen Altarpiece.23Barcelona (Painting index, nos. 466–469). Nevertheless, a set of cross-bars and uprights now began to replace these old-fashioned cross-shaped reinforcements.

The iron cross-members that began to appear in the 16th century instead of wooden ones played a similar role. Pedro Nunyz’ St Eligius Altarpiece, painted around 1526–29, is one example. The cross-bars in this case are recessed.24Barcelona (Painting index, nos. 470–473 and 475).

Reinforcing frames

According to Labande, altarpieces were mostly painted on wood and sometimes on canvas stretched over a frame. When Jacques Mounier produced an altarpiece in 1497 for Saint-Honorat de Lérins, he painted the two side elements on canvas mounted on a frame.25Labande 1932, I: 55. The contract between the Carmelites of Aix and Ogier Batron (or Patron) of Manosque for an altarpiece with wings comprising painted canvases mounted on frames with figures in black and white was signed on 15 March 1526.26Labande 1932, II: 110. Very few of these canvas frames from the late 15th century and early 16th century have survived and so we know little about their construction.27Editors’ note: See Villers 2000. We do not think, however, that it will have differed much from the reinforcing frames used for panels. An example of the latter can already be found in Bernat Martorell’s (ca. 1400–1452) John the Baptist Altarpiece,28Barcelona (Painting index, nos. 456–458). painted around 1425–30 on three poplar panels reinforced by a set of cross-bars and uprights (Fig. 108). Somewhat later, around 1455, Pere Garcia de Benabarre painted a St Quiricus and St Julietta Altarpiece29Barcelona (Painting index, nos. 445–447). on three poplar panels, strengthened in the same way (Fig. 110).

Does this mean that the method was used at the same time as that of cross-diagonal battens? We assume so, as a significant number of 15th-century panels are reinforced in this way. Reinforcing frames represented an improvement, however, and their use continued until the 16th century. Pedro Serafin (active ca. 1560) used a frame like this around 1543 to reinforce the panel on which he painted St Martin on Horseback.30Arénys de Munt (Painting index, no. 489). The St Stephen Altarpiece by the workshop of the Vergos brothers, painted around 1500, is reinforced in the same way.31Barcelona, A Miracle of St Stephen (Painting index, no. 476); Ordination of St Stephen (Painting index, no. 477).

Whatever the case, this assembly method remains exclusive to Spain, and the reinforcing frames we find on the backs of panels from other schools are generally of modern construction. All the ones we have identified – in the Italian schools of Florence, Venice, Verona and Parma – were most likely added in the 19th century.32Information provided by Lucien Aubert, restorer of paintings at the Musée du Louvre. Their authenticity is uncertain at any rate, and only the way the wood has been cut can provide an indication of the period in which the work was done. We will therefore limit our study to examples that belong indisputably to the Spanish schools.

These reinforcing frames are made up of elements mounted on the back of the panel, on all four sides. A varying number of cross-bars link these side members. There can be as many as six of them, as in Pedro Serafin’s St Martin on Horseback, but the average is between one and five.33Painting index, nos. 448, 456, 457, 458, 862 (1 and 2 cross-bars); 450, 451, 452, 454, 461, 463 (2 and 3 cross-bars); 445, 446, 447, 462, 489 (4 and 5 cross-bars). These are all 15th-century panels, with the exception of the one described above, which dates from the mid-16th century. They are all Catalan as well, apart from the late 15th-century Aragonese Coronation of the Virgin by the Master of the Prelate Mur.34Paris (Musée des Arts Décoratifs) (Painting index, no. 862).

Nails

We have come across the extremely curious example of a panel fitted with nails, the purpose of latter being difficult to determine. The work in question is Christ on the Cross by Francesco Francia (ca. 1447–1517).35Paris (Musée du Louvre) (Painting index, no. 561). The nails appear on the edge of the support and plainly serve no purpose in terms of the assembly of either the panel or the frame. So what are they doing there? The edges of the wooden panel were examined at the time of the painting’s transfer. No trace of batons was detected around its sides. The eight nails in question were driven in so deeply that their heads were embedded several millimetres beneath the surface of the wood and had to be dug out. The heads of the nails seem to have been deliberately forged in such a way as to penetrate deep into the wood (Fig. 130). Should we interpret this as a one-off case of a panel being reinforced by a set of nails driven into the wood grain, strengthening it internally, rather than holding it in the customary way with external cross-bars? Comparison of these nails with the ones used for cross-bars in the same period highlights their finesse and their elongated form.36The difference in scale of the nails illustrated in Figs 129–131 makes it hard to compare them properly. Although no firm conclusion is possible, the specific appearance and placement of these nails suggests some kind of armature to strengthen the material.

The frames

The purpose of frames (engaged, rebated, integral, etc.) is not only aesthetic: they also played a significant role in terms of strengthening the support. From the 13th century on, they were fixed to the outside of the supports with nails or dowels, and then the frame was slotted on.37Editors’ note: Many have contributed to a better understanding of integral, semi-integral and applied frames and framing elements during the period in question. See the revised and extended bibliography for examples.

Engaged frame

This type appears to be the oldest.38This statement should be revised, as integral frames would seem to be the oldest. The frame consists of two wooden uprights and two cross-members nailed to the front of the panel (Fig. 118). Its function is aesthetic rather than utilitarian. In some cases, however, the members of the frame are repeated on the back, so that the panel is held firmly between them (Figs 111 and 112). These may be interpreted as the precursors of rebated frames, which were perfected a little later, and which genuinely supported the panel. Frames like this were filled and painted in the same way as the central part of the support, which can make them hard to distinguish from integral frames. Any doubts in that regard are removed, however, by examining the edge of the panel. Three layers can then be clearly distinguished: the frame member, the support and the reinforcing member on the back of the panel.

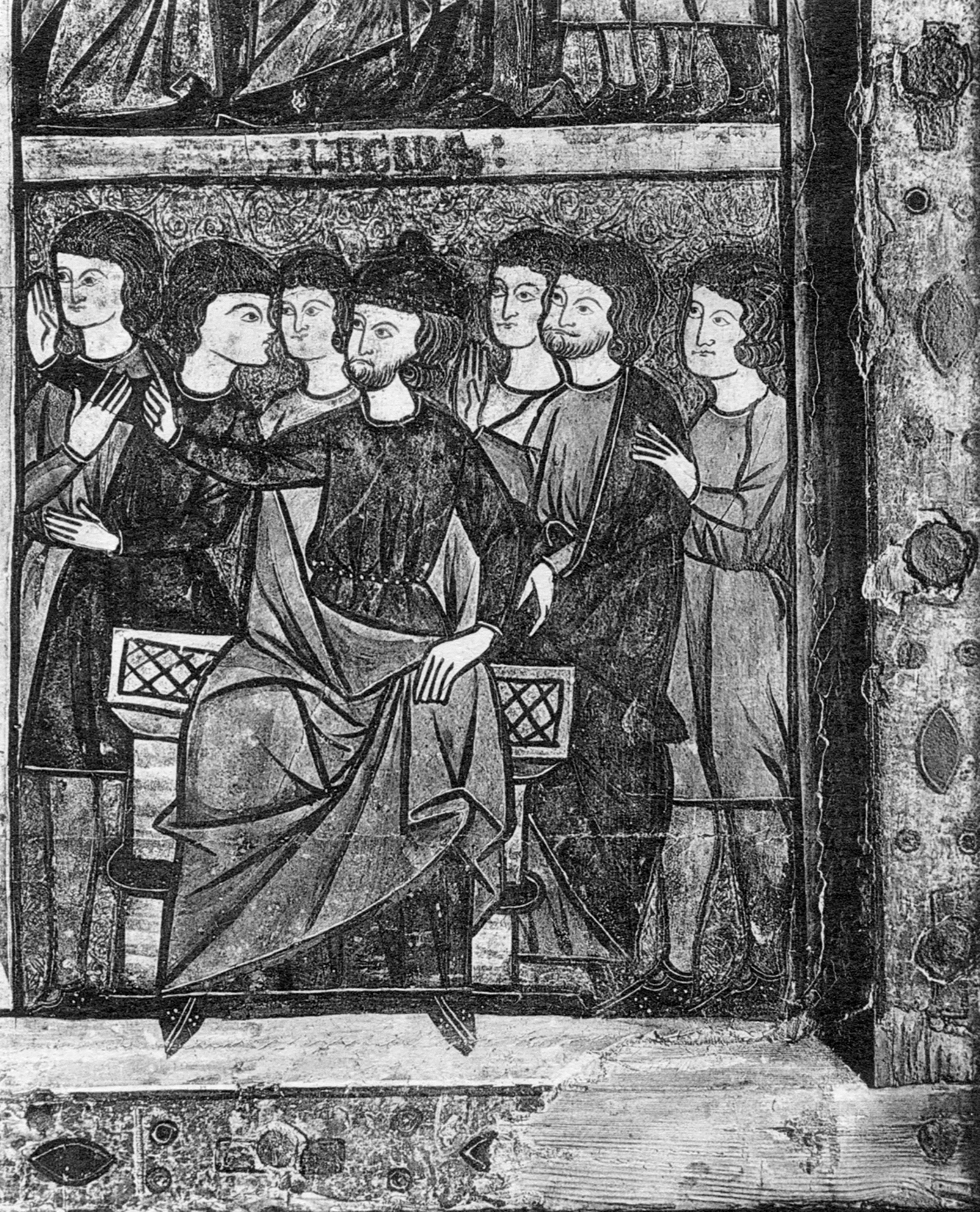

This type of frame is undoubtedly the most primitive. It was used in the 12th–15th centuries, but does not appear to have been employed after that. Rebated frames then became common in all schools of painting. Table 1, which classifies a number of panels framed using this method, allows the technique to be dated.39This is by no means a comprehensive list of panels framed using this method. We have merely selected a few examples. The reader is encouraged to supplement the table by consulting the Painting index.

Table 1 The number of panels framed using the engaged frame method.

Rebated frame

When slotted into the rebate of the frame, the panel is held inside it. The panel, which is mostly painted on the back, is then kept flat, without the addition of cross-bars. Many of these frames have not survived, but panels with thinned edges might be an indication that they were used. This thinning generally takes the form of shouldering on the edges of the panel.40Bevelling is another method for thinning the edges of the panel. We found numerous examples of this in court portraits done in France in the 16th century (Fig. 116), and we even identified a few with roughly cut panels from the 14th and 15th centuries (Fig. 115). While bevelling might have made it easier to slot a panel into a rebated frame, it would also have facilitated the introduction of holding nails inside a engaged frame. We found traces like this in a number of panels, mainly those from the 16th-century German schools. Traces of this kind, which are found either on all four edges or only on the lateral edges, are too fragmentary for us to generalise from them – only those panels that have retained their original frame are worthy of mention. These are, specifically, a Catalan altar frontal,41The Pantocrator and Four Saints, Barcelona (Painting index, no. 870). painted around 1200; the early 15th-century Portuguese Portrait of King John I42Lisbon (Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga) (Painting index, no. 244). (Figs 113 and 114); the Calvary Altarpiece by Vasco Fernandez, painted around 1540;43Viseu (Painting index, nos. 4–7). and various panels from the 15th- and 16th-century German,44Painting index, nos. 1027, 1036, 954–957. French,45Painting index, nos. 168 and 182. Northern Netherlandish,46Painting index, no. 237. and Italian47Painting index, no. 584. schools. This type of frame is very rare prior to the 15th century, but not unknown. We have seen that the rebated frame was known in Catalonia as early as the beginning of the 13th century.

Integral frame

These frames are carved into the mass of the wood, with varying degrees of ornament. The method in question is one of the oldest, if not the oldest of all. Although it differs from the techniques described above, frames like this represent an original way of strengthening the panel. Three French panels were cut this way: the Portrait of King John II ‘Le Bon’ in the Louvre, the Dead Christ, Supported by the Virgin Mary, St John and Two Angels in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Troyes, and the Large Round Pietà, also in the Louvre.48Painting index, nos. 201, 176 and 175. The central part of the wooden panel is gouged out, leaving the edges in relief. These three panels, made between 1360 and 1400, are unique. The technique is not common, no doubt because of the technical difficulties it presents. Carving the frame into the mass of the wood means that the panel cannot consist of more than one board. This limits the size and hence the number of these panels.

It can be difficult to distinguish, however, between a frame mounted on the panel and one carved as an integral part of it. The Louvre panel with the Large Round Pietà, for instance, presents certain contradictory elements. There is no indication that the frame was mounted on the panel, yet the panel appears to be jointed. Four samples of wood taken from all over the surface of the panel back were found to be oak, but three samples taken from precisely the same spot turned out to be oak in one case and fir in two. The latter can only have come from dowels used to assemble the panel. All this suggests that the panel is actually an ensemble of several oak boards, each of which has an integral section of frame carved into it, and which were then assembled using firwood dowels.

Assembly of the reinforcing members

Having previously examined the different techniques for assembling boards, we will now see which procedures were used when connecting the cross-bars and uprights of the reinforcing systems and engaged frames. The technique varies, depending on whether we are dealing with corner, middle, end or through joints. We will provide an example of each of these methods, selected from among the earliest Spanish paintings from the 13th to the 15th century. We would have extended this study to other schools if the original physiognomy of the panels had been preserved intact, which unfortunately was frequently not the case.

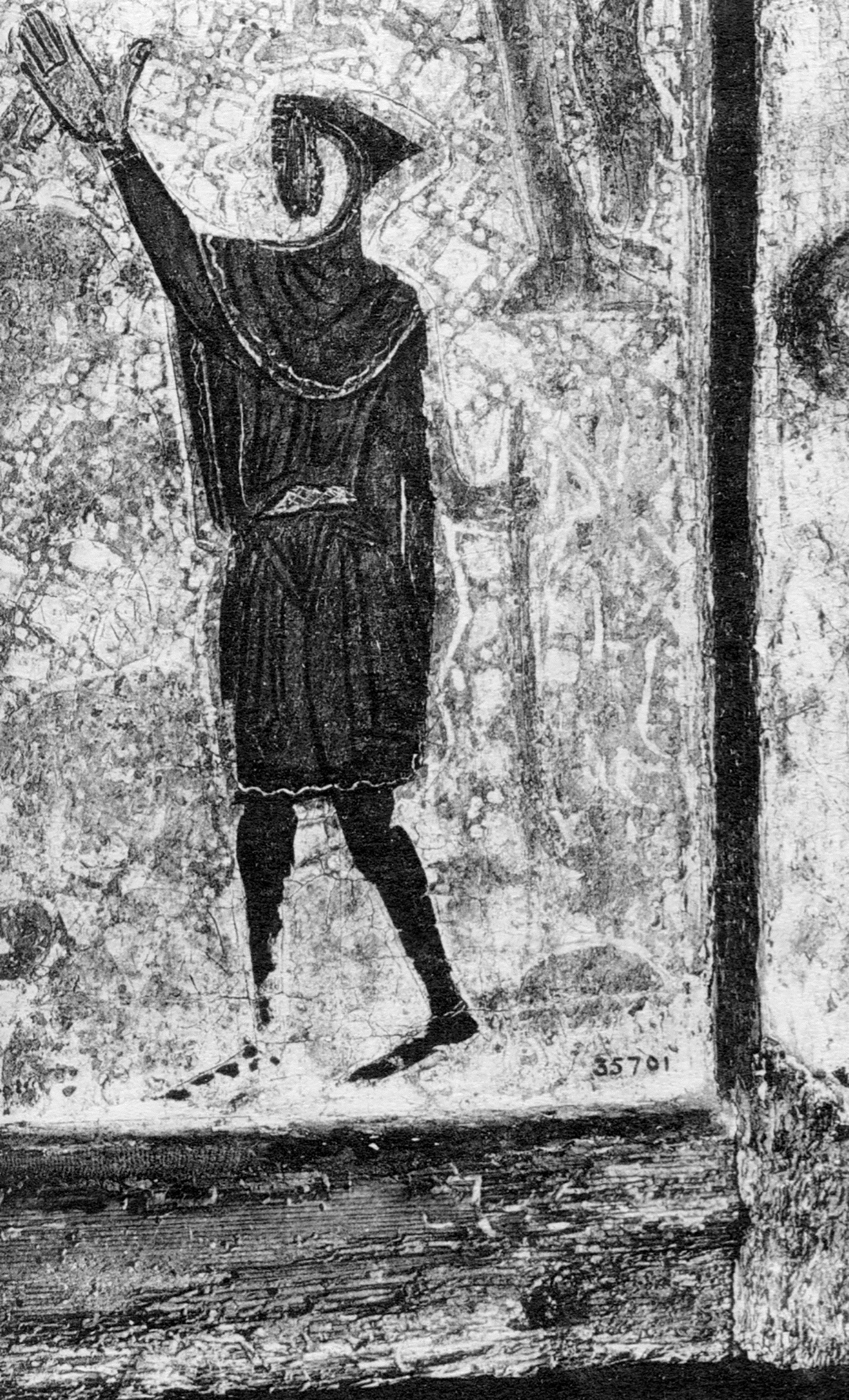

Figure 117 Mortise and tenon corner joint in frame: continuous upright. (Catalan School, 13th century, Scenes from the Life of the Virgin. Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, no. 893.)

Figure 118 Mortise and tenon corner joint in frame fixed by a nail: continuous cross-member. (Aragonese School, 14th century, St Ursula Altarpiece. Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, no. 883.)

Figure 119 Mortise and tenon corner joint between the upright and cross-bar on the back, fixed by a nail. (Workshop of the Vergos brothers, St Stephen Altarpiece. Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, no. 476.)

Figure 120 Scarf corner joint in frame fixed by a dowel. (German School, 15th century, Calvary. Saint-Omer, Museum. Painting index, no. 933A.)

Figure 121 Mitre joint between a cross-bar and a brace (modern frame). (Master of Játiva, Life of the Virgin and of Christ altarpiece. Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, nos. 913–919.)

Figure 122 Butt end joint between cross-bars with mortise and tenon. (Antonio Ronzen, The Crucifixion, central panel. Saint-Maximin, Dominican church. Painting index, no. 418.)

Figure 123 Cross-bar connected in the middle (dovetail). (Catalan School, 16th century, St Christopher and Jesus. Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Painting index, no. 465.)

Figure 124 Fixing of cross-bars to the support (dovetail). (Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin and Child with St Anne. Paris, Musée du Louvre. Painting index, no. 602.)

Figure 125 Cross-bar connected in the middle through the tenon. (Pedro Serafin, St Martin on Horseback. Arénys de Munt, Museum. Painting index, no. 489.)

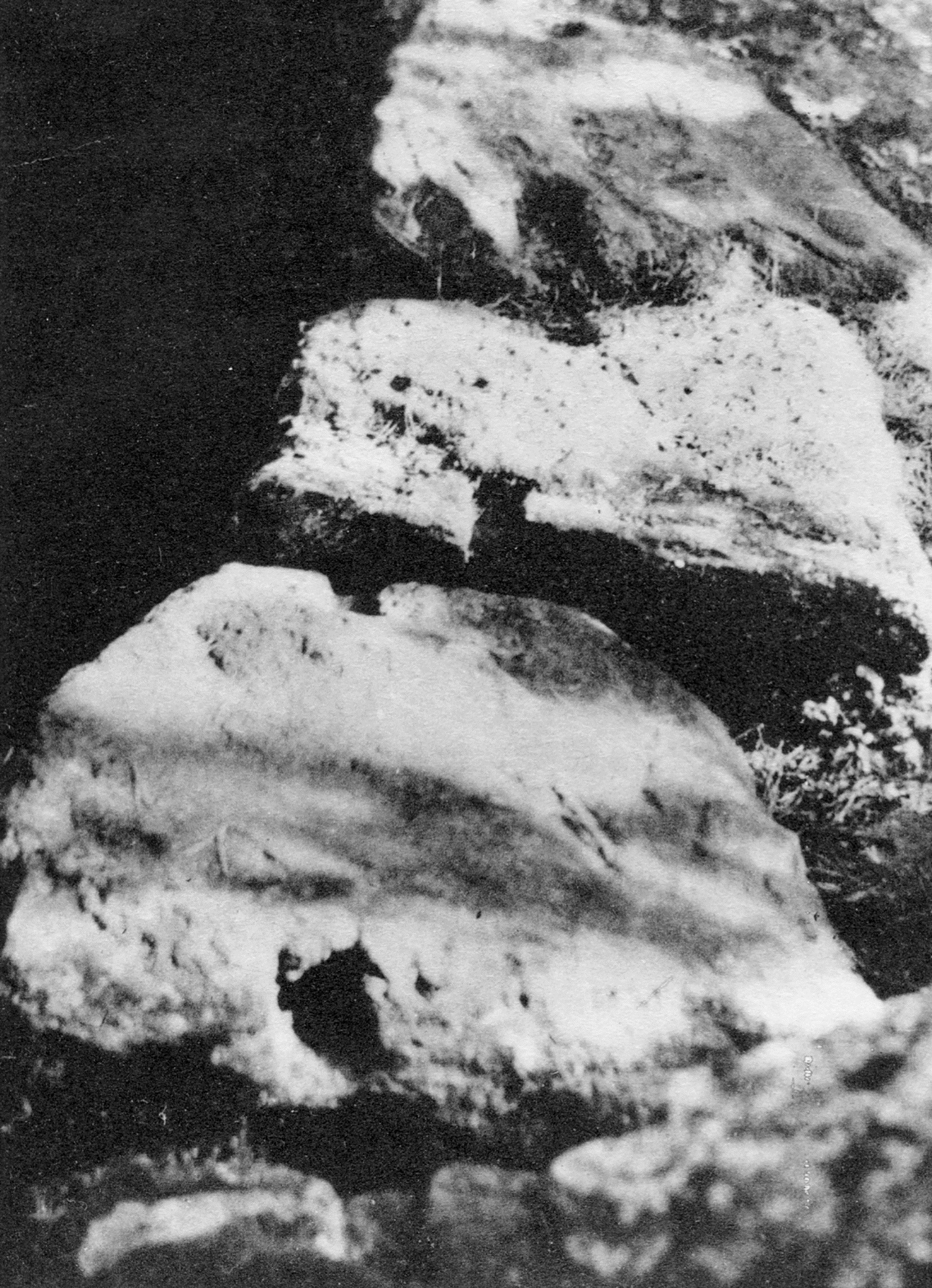

Figure 126 Dovetail joint without any practical purpose. Egyptian builders were aware of the dovetail type of mortise and tenon joint. The one in the photograph was not intended to connect two stones: it has been cut into a single block and serves no practical purpose. Traditional Egyptologists identify this anomaly as some kind of technical aberration. The ‘Symbolists’ see it as intentional, emphasising the connecting function in a single stone (Rambach 1956).

Figure 127 Sainte-Odile ‘Pagan Wall’ (Commune d’Ottrott, arrondissement de Molsheim, Bas-Rhin). This circular wall, running for over 10 km, is built from immense blocks of barely quarried stone. The blocks are joined by oak tenons, larger at the ends and cut into dovetails. This method of assembly is the rule at Sainte-Odile rather than the exception: the wall is constructed this way at all levels (Hansi 1929: 15).

Corner joints

Corner joints are the first major assembly technique in modern carpentry and joinery, whether halved, dovetail, comb, or mortise and tenon. Not all of these variations appear to have been known at the beginning of the Middle Ages.49Editors’ note: The 11th century is currently not regarded as the beginning of the Middle Ages; see the editors’ introduction to this book. Mortise and tenon joints were seemingly the only method used in the Aragonese and Catalan schools in the 14th and 15th centuries. The uprights and cross-members of the frame are joined and then fixed to the panel with a nail or a wooden dowel (Figs 118 and 120).

The same applies to the assembly of the cross-members and uprights of the frame on the back (Fig. 119). Examples include the seven 15th-century panels with the Life of the Virgin and of Christ by the Master of Játiva, a Catalan altar frontal from the 13th century and the St Michael Altarpiece, which Jaume Huguet50Barcelona (Painting index, nos. 913–919, 893, 448 and 449). painted in 1450–56 for the grocers’ fraternity; these are examples chosen at random from the Spanish schools, which offer many more besides. We find the same in Portugal and the Northern Netherlands: the corner joints in the frames of the 15th-century Portuguese Portrait of King John I and Jan van Scorel’s (1495–1562) 16th-century Portrait of a Man,51Lisbon (Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga) (Painting index, no. 244); Amsterdam (Painting index, no. 238). likewise consist of mortise and tenon on both the back and front.

The technical implementation of this assembly method barely varied in the Middle Ages. The end of the cross-member was cut into a tenon and inserted into a mortise made in the upright. The tenon could be made, however, either on the lower cross-member – in which case it is the upright that is continuous – or on the upright – in which case it butts against the lower cross-member, which is then continuous (Figs 117 and 118).

The scarf joint is a variation on this method (Fig. 120). In this case, tenons are cut on each of the two pieces to be joined, matching the mortise made to receive the tenon of the other piece. The cavity suggests that an additional form of fixing, such as a now lost wooden dowel, was used to stiffen the overall assembly. This rarely used system is found in the frame construction of Christ Appearing to Mary Magdalene, a 15th-century copy after an engraving by Martin Schongauer (1448–1491).52Strasbourg (Painting index, no. 1027). This painting is thought to date from the same period as the Calvary in the Museum of Saint-Omer.53German School, 15th century (Painting index, no. 933A). The latter is attributed to the German School, which would make this the standard assembly method for that school, if it were not for the fact that the attribution has been contested.54Editors’ note: Conclusions on standard assembly methods for framing elements in the late medieval period have yet to be drawn but are currently under investigation as part of a number of research initiatives. These include the major project ‘After the Black Death: Painting and Polychrome Sculpture in Norway', led by Dr Noëlle Streeton and Professor Tine Frøysaker, Conservation Studies, University of Oslo, working closely with researchers at the CATS Centre in Copenhagen. The project is supported between 2014 and 2017 by a substantial grant from the Research Council of Norway (ES512866). The cross-bars are joined here at right angles. They can also meet at an angle (Fig. 121), in this case by simple juxtaposition, apparently with no further system of assembly.

The diagonal braces used as reinforcement on Spanish panels were not, therefore, fixed to the cross-members but directly to the support itself;55Cf. Figs 104–107 and 109; Painting index, nos. 913–919 and 461–464. in this specific case, there is no corner joint at all, strictly speaking. The cross-bars meet but are not physically joined, similar to the situation with butt joins.

Middle joints

Two types of middle joints were used in Spain: the ‘through tenon’ and the ‘dovetail’. These two mortise and tenon-type joints not only differ from corner joints, but also from each other. The difference lies chiefly in the shape of the tenon. In the ‘through tenon’, the tenon is straight and goes all the way through the piece into which it is fitted; the second type of tenon is a dovetail and is inserted in a mortise of the same shape (Figs 123 and 125). The shape of the motise and tenon ‘dovetail’ recalls that of a tail of a swallow to which it owes its name (aronde or hirondo in old French). Dovetail joints are known to be the oldest technique of their kind. They feature in the ‘Pagan Wall’ at Sainte-Odile in the Vosges (Fig. 127) and date back far into antiquity (Fig. 126).56Editors’ note: Wadum 1998a: 154: ‘If butterfly keys were used, they were placed mainly on the front of the panel. Butterfly keys on the backs of panels are usually later additions. As panels became thinner toward the end of the 16th century, dowels replaced the butterfly keys for stabilizing and aligning the joins during gluing.’

Fourteenth- and 15th-century documents relating to the Chartreuse in Dijon provide us with certain additional information. One refers to: ‘Carpentry and fashioning of two doors for the portal of the church of the said Chartreuse ... which doors are strengthened [enfonciées], bouhées and nasselées at the front ... and reinforced at the back by intersecting cross-members with dovetail joints [à queue d’aronde].’57Monget 1898: 197. Another records: ‘Jehan de Beaumez working with his painters on the vault of the church on a long platform.’ The vault was constructed by the carpenter Denis Pychon, and is described in the contract as ‘an arch, five feet long, with dovetails [à queue d’aronde ]’.58Monget 1898: 130. Joints of this type, used in carpentry in the 14th century, were likewise employed by joiners. We find them, for instance, in the middle of the cross-members of certain panels by Bernat Martorell, Jaume Huguet, Pere Garcia de Benabarre and numerous anonymous Catalan panels from the 16th century59Barcelona (Painting index, nos. 445, 447, 448, 450–454, 456–458 and 462–465). (Figs 108, 110 and 123).

In some cases, the cross-bar is cut into dovetails not only at either end, but for the whole of its length. In this instance, it is fixed directly to the panel, in which a mortise of the same shape is cut directly all the way across, rather than being fixed to the uprights of a reinforcing frame. Leonardo da Vinci’s Virgin and Child with St Anne (Fig. 124) provides a good example of this, although it is difficult to cite others. It is indeed the case that while the cross-bars of many panels are fitted into dovetail recesses in the support, the majority of these are of more or less recent date. Many were done in the 19th century. We therefore have only retained the above examples. All these dovetail joints attach cross-bars either to the uprights of a reinforcing frame or to the support itself. A different method was required when connecting cross-bars from different panels.

End joints

These belong to the second major category of joinery and carpentry joints in our period. They are also referred to as ‘scarf joints’ and ‘cross-wise joints’. Scarves can be cross-lap joints, simple butt joints, dovetail, splayed, and various types of slot mortise. Scarf joints were used in the Middle Ages to join several panels together when constructing polyptychs, for which wooden dowels proved inadequate. Cross-members were then added for reinforcement. These were connected using plain butt end or dovetail joints. Both types are only found in the construction of supports. They are derived from mortise and tenon joints.

The cross-member in the Altarpiece of the Passion by Antonio Ronzen60The Crucifixion, Saint-Maximin, Dominican church (Painting index, no. 418). features an example of a plain butt end joint. The mortises made in this member open up its outside surface completely at one end, while at the other, only the bottom is grooved; this mortise was intended to receive the tenons of the cross-bars of neighbouring panels (Fig. 122).

The dovetail scarf joint is found in the reinforcing frame of three panels from the St Quiricus and St Julietta Altarpiece, painted by Pere Garcia de Benabarre.61Barcelona (Painting index, nos. 445–447). Although it was made almost a century before Antonio Ronzen’s altarpiece, the Catalan work shows greater technical refinement. Assembly techniques no doubt varied according to the size of the altarpiece. Ronzen’s polyptych is a major piece of work, which would have demanded a solid framework, of which the central panel’s cross-member was the linchpin.

1 Editors’ note: Vasari et al. 2005: 385. Vasari describes the method of applying canvas or linen to the panels before grounding and painting them. In his description, the linen not only had the advantage of covering unevenness and joints in the board but also offered a good grip for the ground (Berger 1901). »

2 Madurell Marimon 1950: 143, 151, 156, 165, 218, 328. »

3 Editors’ note: Cennino Cennini (ca. 1437) advised his fellow Italian painters to take some canvas or white-threaded old linen cloth, soak strips of it in sizing, and spread it over the surface of the panel or ancona; see Cennini 1859: ch. 114: ‘Come si dè impannare in tavola’ (‘How to put a cloth on a panel’). »

4 Editors’ note: See Véliz 1998a. Antwerp altars more than 2 m high required the back to be secured by transverse battens – one at the neck, with more behind the main corpus. This requirement was incorporated in a new set of rules received by the Antwerp guild of Saint Luke on 20 March 1493 (Van Der Straelen 1855: 30–35). »

6 Madurell Marimon 1944: 147. »

7 The above paintings correspond with the following numbers in the Painting index: 891, 873, 441, 448–454, 904, 445–447 and 823. »

8 Madurell Marimon 1944: 155, 166, 205. »

12 Madurell Marimon 1950: 151, 156, 165, 328. »

14 Editors’ note: See the study of a late 16th-century Castilian altarpiece including a complete technical documentation of the altarpiece in all its aspects. »

17 Editors’ note: Example of transversal bars fixed on to the frame: A. Bouts, Triptych of the Assumption of the Virgin, Inv. no. 574, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique/Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België. »

25 Labande 1932, I: 55. »

26 Labande 1932, II: 110. »

31 Barcelona, A Miracle of St Stephen (Painting index, no. 476); Ordination of St Stephen (Painting index, no. 477). »

32 Information provided by Lucien Aubert, restorer of paintings at the Musée du Louvre. »

33 Painting index, nos. 448, 456, 457, 458, 862 (1 and 2 cross-bars); 450, 451, 452, 454, 461, 463 (2 and 3 cross-bars); 445, 446, 447, 462, 489 (4 and 5 cross-bars). »

36 The difference in scale of the nails illustrated in Figs 129–131 makes it hard to compare them properly. »

37 Editors’ note: Many have contributed to a better understanding of integral, semi-integral and applied frames and framing elements during the period in question. See the revised and extended bibliography for examples. »

38 This statement should be revised, as integral frames would seem to be the oldest. »

39 This is by no means a comprehensive list of panels framed using this method. We have merely selected a few examples. The reader is encouraged to supplement the table by consulting the Painting index. »

40 Bevelling is another method for thinning the edges of the panel. We found numerous examples of this in court portraits done in France in the 16th century (Fig. 116), and we even identified a few with roughly cut panels from the 14th and 15th centuries (Fig. 115). While bevelling might have made it easier to slot a panel into a rebated frame, it would also have facilitated the introduction of holding nails inside a engaged frame. »

49 Editors’ note: The 11th century is currently not regarded as the beginning of the Middle Ages; see the editors’ introduction to this book. »

51 Lisbon (Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga) (Painting index, no. 244); Amsterdam (Painting index, no. 238). »

54 Editors’ note: Conclusions on standard assembly methods for framing elements in the late medieval period have yet to be drawn but are currently under investigation as part of a number of research initiatives. These include the major project ‘After the Black Death: Painting and Polychrome Sculpture in Norway', led by Dr Noëlle Streeton and Professor Tine Frøysaker, Conservation Studies, University of Oslo, working closely with researchers at the CATS Centre in Copenhagen. The project is supported between 2014 and 2017 by a substantial grant from the Research Council of Norway (ES512866). »

56 Editors’ note: Wadum 1998a: 154: ‘If butterfly keys were used, they were placed mainly on the front of the panel. Butterfly keys on the backs of panels are usually later additions. As panels became thinner toward the end of the 16th century, dowels replaced the butterfly keys for stabilizing and aligning the joins during gluing.’ »

57 Monget 1898: 197. »

58 Monget 1898: 130. »